University of Nebraska at Omaha University of Nebraska at Omaha

DigitalCommons@UNO DigitalCommons@UNO

Writer’s Workshop Faculty Publications Writer's Workshop

4-2023

Rethinking Length and Form in Fiction: Workshopping Short Rethinking Length and Form in Fiction: Workshopping Short

Stories, Novels, Novellas, Flash, and Hybrid Stories, Novels, Novellas, Flash, and Hybrid

Kevin Clouther

Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/wrtrswrkshpfacpub

Please take our feedback survey at: https://unomaha.az1.qualtrics.com/jfe/form/

SV_8cchtFmpDyGfBLE

Rethinking Length and Form in Fiction 1

Rethinking Length and Form in Fiction:

Workshopping Short Stories, Novels, Novellas,

Flash, and Hybrid

Kevin Clouther

University of Nebraska at Omaha

There is an appealing simplicity to the idea that to write ction well, you must rst learn to

write a short story. Easier to write fteen pages than 300, especially if the student is learning the

elements that will allow her to succeed. Easier for the instructor to critique fteen pages than 300.

I won’t argue against this logic. If a student wants to write short stories because she loves short

stories, or if a student wants to learn how to write a short story before moving to a novel, then a

ction workshop is an ideal place for the student to improve her craft.

Indeed, if I had a steady stream of undergraduate and graduate students who revered short

stories and wanted nothing more than to write their own, then I would not have written this

essay. In twenty years teaching creative writing at the college level, something closer to the

opposite has been true. Few of my students regularly read short stories on their own, and few

prefer to write them. My students read and want to write other kinds of ction: not only novels

but also novellas, ash, and hybrid.

When I was an undergraduate at the University of Virginia in the late 1990s, the “Kmart

realism” of writers such as Ann Beattie, Richard Ford, and Bobbie Ann Mason was in vogue.

Raymond Carver impersonations were widespread. In a 1995 essay in Studies in Short Fiction,

Miriam Marty Clark wrote that these short stories “represent the colonization of private life

by consumer capitalism” (150). This was the thinking that informed my early writing and—

by extension—early teaching. I lled my rst syllabi with writers I’d read as an undergradu-

ate, writers sensitive to consumerism and class, which resonated with me as a rst-generation

student at an auent public university. Many of my undergraduates now are rst-generation

students, and I assign short stories with characters who hold the factory and service jobs that so

many of the students and their family members work.

PEDAGOGY

1

Clouther: Rethinking Length and Form in Fiction

Published by RIT Scholar Works, 2023

Journal of Creative Writing Studies 2

I don’t teach as many of these writers as I used to, however. I am conscious of other kinds

of representation—few of the characters I read as an undergraduate were people of color, for

instance, or people with disabilities—and I am conscious of how little of the ction that my

students read and write is grounded in literary realism. They are more likely to read and write

fantasy or science ction. They are as likely to reference television or lm as short stories or

novels. Video games inspire many of my students’ sense of narrative.

Making the short story the default, if not only, form permitted in ction workshops limits the

writing that students submit but it does something more signicant: it narrows students’ sense of

what writing can be. In conning discussion to short stories, instructors risk discouraging, alien-

ating, or even losing students who might be more familiar with and interested in other forms.

The primacy of the short story is just one of many assumptions that have been ignored in

workshops. Two books published to considerable attention in 2021, Felicia Rose Chavez’s The

Anti-Racist Writing Workshop: How To Decolonize the Creative Classroom and Matthew Saless-

es’s Craft in the Real World: Rethinking Fiction Writing and Workshopping, examine how work-

shops have historically centered whiteness. I hope this essay can complement the work that

Chavez and Salesses have done in 1) questioning fundamental assumptions of workshops and 2)

oering more inclusive models.

Before moving forward, I would like to note an important dierence between a workshop

inclusive of form and a workshop inclusive of identity. A workshop that doesn’t allow students to

submit novel excerpts limits—unnecessarily, I will argue—what will be discussed, but it doesn’t

limit who can participate. The aspiring novelist in a short story workshop can still benet from

studying technical elements, such as dialogue and voice. By contrast, a workshop that marginal-

izes writers on the basis of identity precludes certain writers from truly participating independent

of the form(s) they pursue. Building and maintaining workshops inclusive of identity should be a

priority for all instructors, regardless of what they workshop.

The earliest creative writing programs were disproportionately attended and staed by white

cisgender men who disproportionately read the ction of other white cisgender men, but work-

shops today are more diverse in student and faculty populations, and it’s not dicult to ll syllabi

with short stories that present dierence in race, gender, sexual orientation, etc. Although I will

argue against the primacy of the short story in workshops, I will not argue against the short story.

No single list can capture the breadth of the contemporary short story, but a look at recent

winners of the Story Prize, a book prize awarded by independent judges to the year’s best short

story collection, oers a microcosm of the vitality of the form. Deesha Philyaw won the 2020 prize

for The Secret Lives of Church Ladies, which centers Black and queer women. Edwidge Danticat

2

Journal of Creative Writing Studies, Vol. 8, Iss. 1 [2023], Art. 8

https://scholarworks.rit.edu/jcws/vol8/iss1/8

Rethinking Length and Form in Fiction 3

won the rst prize in 2004 for The Dew Breaker and the 2019 prize for Everything Inside; each

book moves between Haiti, where Danticat was born, and Florida, where she later lived. Other

winners include the Irish writer Patrick O’Keee (The Hill Road 2005), the Pakistani-American

writer Daniyal Mueenuddin (In Other Rooms, Other Wonders 2009), and the American writer

Jim Shepard (Like You’d Understand, Anyway 2007), whose short stories explore the “Chernobyl

nuclear meltdown and it’s (sic) aftermath, a Roman outpost in hostile Britannia, a Nazi expedi-

tion in Tibet, a Texas hotbed of high school football, a female cosmonaut preparing for a Sputnik

launch, and the executioner’s scaold in revolutionary France” (“The Story Prize”).

Before presenting alternatives to workshops that privilege the short story, let me rst praise

the short story.

Because the short story can be read in a single sitting, there is a congruity to the form absent

from longer forms. The various aspects of the short story work together and at once. Nothing is

extraneous or forgotten. (I’m referring to unusually good short stories; any number of things are

extraneous or forgotten in less successful examples.) Rust Hills stated in Writing in General and

the Short Story in Particular (1977) that the “successful contemporary short story will demonstrate

a more harmonious relationship of all its aspects than will any other literary art form, excepting

perhaps lyric poetry” (1) and that “there is a degree of unity in a well-wrought story… that isn’t nec-

essarily found in a good novel, that isn’t perhaps even desirable in a novel” (3). In A Swim in a Pond

in the Rain: In Which Four Russians Give a Master Class on Writing, Reading, and Life (2021),

George Saunders presented a similar case, noting that the “story form makes a de facto case for e-

ciency. Its limited length suggests that all of its parts must be there for a purpose. We assume that

everything, down to the level of punctuation, is intended by the writer” (327).

The shortness of the short story makes it well-suited for workshops. At the University of

Nebraska Omaha (UNO), where I teach in the Writer’s Workshop and direct the low-residency

MFA in Writing, undergraduate ction studios meet once a week, and I workshop two or three

students per session. During graduate residencies, faculty dedicate an hour-long workshop per

student. Unlike novel or novella excerpts, short stories generally conform to Aristotle’s notion in

Poetics of a whole as “that which has a beginning, a middle, and an end”:

A beginning is that which does not itself follow anything by causal necessity, but after which

something naturally is or comes to be. An end, on the contrary, is that which itself naturally

follows some other thing, either by necessity, or as a rule, but has nothing following it. A middle

is that which follows something as some other thing follows it. A well constructed plot, there-

fore, must neither begin nor end at haphazard, but conform to these principles. (14)

3

Clouther: Rethinking Length and Form in Fiction

Published by RIT Scholar Works, 2023

Journal of Creative Writing Studies 4

I’m sympathetic to the idea that students need to write —and fail at writing well—short stories

before attempting a novel or novella. Short stories present a laboratory where students can test

dierent attempts at point of view, tense, tone, etc. before applying them to longer forms. Because

ash compresses the elements of the short story, it may help to write 5,000-word short stories

before writing 500-word stories. Similarly, it may help to learn traditional forms before moving

to experimental or hybrid forms. I will address all of these concerns later in this essay.

I also want to praise the short story because of how meaningful it has been to me as a reader.

Alice Munro’s short stories recongured the way I think about memory. Yiyun Li’s short stories

widened my understanding of grief and loss. In the short stories of Anton Chekhov, as trans-

lated from Russian by Constance Garnett and then Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky, I

recognized my own thoughts in spite of dierences in language, culture, geography, and time. I

still remember reading Shirley Jackson’s “The Lottery” (1948) as a freshman in high school and

thinking to myself: you can do this? It was a wonderful question to ask.

I assign short stories in my classes because I believe that students can learn a lot from them.

I hope that short stories will move students as I have been moved, and I hope that short stories

will move students in ways personal to them. I don’t only assign short stories, though, and I don’t

require that students write them. I will dedicate the rest of this essay to answering the follow-

ing question: how can a ction workshop accommodate various lengths and forms? Because the

short story historically has been the dominant form in ction workshops, I will begin there before

addressing the novella and novel, which is the form my students most often want to write. I will

dedicate one section to ash and another section to hybrid. I will conclude by arguing why ction

workshops need to make space for dierent lengths and forms.

1. WORKSHOPPING SHORT STORIES

Almost all ction workshops I’ve attended going back to my rst workshop as an undergradu-

ate have looked something like this: a student submits a short story, typically ten to twenty dou-

ble-spaced pages in length; the other students in the class are given time to read the short story

in advance, make line edits, and write the author an editorial letter about what’s working and

what the author might consider revising; once a workshop begins, the author remains silent with

perhaps two exceptions: the author may read a short excerpt at the beginning, and the author may

ask questions at the end; sometimes students address the author while her short story is being

workshopped, but often the class acts as though she isn’t in the room; the emphasis is on the text

and not the author’s intentions; although the instructor moderates the discussion, her voice is one

of many in the room, and everyone is expected to contribute.

4

Journal of Creative Writing Studies, Vol. 8, Iss. 1 [2023], Art. 8

https://scholarworks.rit.edu/jcws/vol8/iss1/8

Rethinking Length and Form in Fiction 5

As a ritual, the workshop is formal and designed to be repeated. Indeed, someone who begins

taking workshops as an undergraduate—if not earlier—before moving to an MFA or PhD and

then writing groups or writing conferences or a career teaching writing can expect to participate

in hundreds, even thousands, of workshops with meaningful variation only in the people in the

room and the work being discussed. Given the ubiquity of this model, it’s surprising not that it’s

being questioned but that it has survived for so long.

I won’t argue that this model needs to be detonated. On the contrary, I admire many of the tra-

ditions within it and suspect that it has endured, in part, because it serves a wide range of artistic

aims, even if it was designed more narrowly. I will argue that instructors and program directors

need to rethink certain practices and that these practices require more than a touching up; in com-

municating the types of writing that students are permitted to submit, classes and programs com-

municate what they do and don’t value.

One of the earliest indicators of values is the course syllabus. Frequently, this document is

posted online before the semester starts. Students nervous about generating new work or, alter-

natively, eager to have as much work critiqued as possible may look to the syllabus to see what

they’re allowed to submit.

Although I believe that workshops need to be exible with length and form, I don’t believe

that students ought to be able to submit any number of pages for the simple reason that it’s unfair

to other students, who have various academic, work, and family responsibilities. Workshops

don’t occur in vacuums, and students attend class between other classes, jobs, childcare pick-ups,

etc. Since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, the boundaries separating these responsibili-

ties have blurred, if not collapsed, as any participant of a workshop on videoconference knows.

(One time my students complained of a thin whistling noise in their audio before I realized it was

my wife making tea; several times my daughter absently wandered onto my screen—these are

benign examples compared to students sharing computers or participating from mobile phones or

sitting in parking lots, where students can access Wi-Fi.) Nor would it be practical to discuss, for

example, an 800-page novel in an hourlong workshop. It may have been done, but I doubt it can

be done well. I specify an upper-page limit on the syllabus and encourage students to talk with me

if they want to exceed that limit. If the limit for a workshop is twenty pages and a student wants

to submit twenty-three pages, then I likely grant an exception. If a student wants to submit fty

pages, then I help her determine how to submit fewer pages.

In undergraduate workshops, I give students a week to read each short story, and I clarify

on the syllabus what I expect in terms of line edits and editorial letters. The guiding principle

is something like the Golden Rule: critique students’ ction as you would want your own ction

5

Clouther: Rethinking Length and Form in Fiction

Published by RIT Scholar Works, 2023

Journal of Creative Writing Studies 6

critiqued. Critiques include both written feedback and in-class participation. In The Anti-Racist

Writing Workshop, Chavez addressed the importance of accountability:

Your workshop participants of color don’t need you to soften your policies for them. Just the

opposite. Try demanding more of them: Show up, on time, every time. Well-meaning col-

leagues have criticized my mandatory attendance policy as unnecessarily harsh and unrealistic.

But a lesson I want to impress upon my workshop participants is that life is a series of conspira-

cies to keep us from exercising voice. To be a writer is to choose to write, to show up every day

and do the work. There’s always an excuse not to. (48)

My workshops begin with the author’s reading from her work, as I want students to hear the short

story in the author’s own voice before we begin critiquing her work. Once the author nishes reading,

she remains silent until the end when she’s invited to ask questions. Before students comment on the

short story, I ask one student to provide a yover or brief summary of the piece. This both reminds the

class of the material and allows the author to hear her work as one reader understood it.

There are various alternatives to the workshop model where the author remains silent while

her ction is workshopped. One well-known model is Liz Lerman’s Critical Response Process,

which begins with participants stating what was “meaningful, evocative, interesting, exciting, and/

or striking in the work.” My workshops proceed similarly but diverge with Lerman’s next step: “The

artist asks questions about the work. In answering, responders stay on topic with the question and

may express opinions in direct response to the artist’s questions.” Although this process resembles

the end of my workshops, the re-ordering is signicant. In Lerman’s model, the artist—and not the

responders—dictates what is and isn’t discussed. Her nal steps are as follows:

Step 3. Neutral Questions

Responders ask neutral questions about the work, and the artist responds. Questions are neutral

when they do not have an opinion couched in them…

Step 4. Opinion Time

Responders state opinions, given permission from the artist; the artist has the option

to say no. (Lerman)

It’s not dicult to see the benets of putting the writer in an active role, dictating what to discuss

in her short story, rather than a passive role, where she listens to whatever workshop participants

wish to discuss. As an instructor, I regularly steer conversation away from tangents that have more

to do with the participant speaking than the short story. As a student, I remember cringing as partici-

pants debated what I perceived to be a basic misreading of the text. Whether this was a result of their

6

Journal of Creative Writing Studies, Vol. 8, Iss. 1 [2023], Art. 8

https://scholarworks.rit.edu/jcws/vol8/iss1/8

Rethinking Length and Form in Fiction 7

inattention or my inexpert prose or a combination of the two didn’t matter; I felt as though my time

and the time of my peers had been used poorly. Why couldn’t I simply tell everyone what I meant?

When I asked this question to Frank Conroy, who directed the Iowa Writers’ Workshop from

1987 to 2005, he told me that when your book is published, you don’t get to put your arm around

the reader’s shoulder and explain what you wanted to say. The expectation was that I would publish

a book and that it would have readers: the book would have to speak for itself, and workshop was

preparation for that time. Conroy was an imposing gure, tough on short stories and sparing with

praise, but I believed that he believed in his students, all of whom he’d admitted to the program.

Each instructor has her own pedagogical approach, and I’m not as severe with students’ ction

as Conroy was with mine. His high standards for the short story have stayed with me, however, as

has the condence he showed in me as a writer. I want students to think of themselves as writers.

That may seem self-evident, but many of my students—even graduate students—confess that they

don’t. When we meet to conference, they sometimes cite imposter syndrome. Convincing students

to think of themselves as writers starts with taking their writing seriously. Although I limit how

much I speak, I am an active facilitator throughout workshop: inviting participants to comment

on other participants’ observations, encouraging disagreement, and insisting that everyone stay

focused on the writing during discussion. If I model these practices early and consistently, then

students are more or less able to run workshops themselves by the end of the semester.

It might be uncomfortable to hear workshop participants read your work dierently from how

you intended it, but in a workshop where everyone is expected to read the work closely, partici-

pants are adept at diagnosing places where the short story could be improved. I tell students that

workshops are good at guring out what needs to be revised, though it’s typically up to the writer

to determine how to revise it. I nd that writers are frequently unaware of major shortcomings in

their own writing. Workshops allow authors to see things that they otherwise would have missed,

but this is harder to achieve when the author is setting the terms for discussion. An author focused

on character development, for example, may miss a structural shortcoming that undermines the

entire piece. In my rst workshops as a graduate student, I was so preoccupied with technical

prociency—with, in retrospect, proving myself—that I repeatedly overlooked aws in point of

view that participants noted en masse. The consistency of their feedback convinced me that I’d

missed something fundamental.

As an instructor, I point repeatedly to the mystery of writing. I expect writers to have a com-

prehensive understanding of neither what they wrote nor how they wrote it. Lan Samantha Chang,

Conroy’s successor as Program Director of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, captured this mystery

powerfully in a 2017 essay for Lit Hub:

7

Clouther: Rethinking Length and Form in Fiction

Published by RIT Scholar Works, 2023

Journal of Creative Writing Studies 8

We make art about what we cannot understand through any other method. The nished product

is like a pearl, complete and beautiful, but mute about itself. The writer has given us this piece

of his interior and there is frequently no explanation, nothing to be said about it. Often, the

writer himself has very little idea of what he has created.

Workshops where the author curates what’s discussed foreclose the possibility that readers have

noticed in the short story weaknesses as important as the ones the author has identied herself. Once

a short story is published, readers co-create the work. There is no meaning for the reader until she

makes meaning herself. Workshops where the author remains silent honor this co-creation with the

crucial dierence that the author has the ability to revise the short story, based on readers’ feedback.

The tradition of acting as though the author isn’t in the room has always struck me as contrived.

I’ve workshopped short stories where the author wasn’t in the room—because, for instance, she was

unexpectedly absent—and these workshops have both been useful for the participants and unam-

biguously dierent from workshops where the author was there. Even if an author isn’t named, her

physical presence aects how people speak, and I see no reason to ignore this. I address the author

by name and encourage participants to do the same (e.g. I’m interested in Luna’s use of backstory

and wonder if they might include a scene where the mother challenges the father through dialogue).

As mentioned previously, I leave time at the end of workshop for the author to ask questions. I insist

that this not be a time for the author to explain her intentions or quibble with readers’ interpreta-

tions, though conversations like this may occur organically after class without the instructor’s mod-

eration. I see these informal sessions as a natural complement to the formal ritual of the workshop.

2. WORKSHOPPING NOVELS AND NOVELLAS

If you’ve participated in the workshop of a novel or novella, then there’s a good chance that dis-

cussion turned at one point to what wa sn’t being workshopped. For readers raised on Aristotle—

even if they never read Poetics themselves—ction without a beginning, middle, and an end is nec-

essarily incomplete. Instructors are wise to acknowledge this mindset, and I will oer in this section

a model for workshopping novels and novellas in a workshop designed for short stories.

First, instructors have to do what many instructors are loath to do: admit that not all students—

perhaps not even most students—want to write short stories. Although students, eager to please

their instructor or conform to the class’s expectations, will dutifully submit short stories, this ction

might not reect what students actually want to write.

I am suspicious of any pedagogy that doesn’t take into consideration what students hope to

learn. That the ction workshop has privileged short stories since its infancy does not mean that it

can’t adapt to other lengths and forms now.

8

Journal of Creative Writing Studies, Vol. 8, Iss. 1 [2023], Art. 8

https://scholarworks.rit.edu/jcws/vol8/iss1/8

Rethinking Length and Form in Fiction 9

One might wonder why a program can’t oer dierent workshops for dierent forms: one for the

short story, one for the novel, one for ash, etc. Large programs may be able to oer these courses,

but most programs don’t have the luxury (or desire) to do so. As such, I will present a semester-

long workshop open to various lengths and forms. I will take as my starting point the workshop

format described in the preceding section. Fiction students—especially students pursuing a degree

in creative writing—will likely be familiar with a version of this format, even if the one I outlined

diers in certain areas. For instructors willing to reimagine the ction workshop, there are advan-

tages to a space that welcomes forms beyond the short story while still leaving room for the short

story, which has proven its suitability for the space.

When instructors accommodate novel or novella excerpts, they frequently emphasize stand-alone

excerpts, the sort of ction that could pass as a short story. Before Jennifer Egan published the Pulitzer

Prize-winning A Visit from the Goon Squad (2010), several excerpts appeared in The New Yorker:

“Found Objects” (2007), “Safari” (2010), “Ask Me if I Care” (2010). While stand-alone excerpts are an

appealing option, not all novel or novella excerpts lend themselves naturally to this format. Given the

publishing industry’s appetite for novels as opposed to short story collections, well-meaning instruc-

tors risk giving students bad advice in the interest of preserving existing workshop models.

Novel excerpts and short stories aren’t interchangeable. Although the former can resemble the latter,

especially out of context, a writer who divides her novel into pieces that look like short stories may nd

that she’s writing and revising the novel in a manner that’s more damaging than helpful. If a short story

is a mile, then a novel is—forgive the metaphor—a marathon. A runner’s mile splits might vary over the

course of twenty-six miles, but at no point does a runner confuse the marathon for a mile.

Pace is a clear place to highlight dierence, but characterization works similarly. Think of how

gradually Leo Tolstoy introduced the reader to Anna Karenina over the course of the novel. Compare

her to Ivan Ilych in Tolstoy’s novella The Death of Ivan Ilyich (1886). Compare him to Vasili in Tol-

stoy’s short story “Master and Man” (1895). In all three narratives, the protagonist dies in the ending:

same outcome, dierent processes. Of the three, I would be most apprehensive workshopping The

Death of Ivan Ilyich. Anna Karenina (1878) contains sections that read like stand-alone pieces, but

where would Tolstoy begin or end The Death of Ivan Ilyich other than where it begins and ends?

More recent case studies can be found in the ction of Mary Gaitskill and Lauren Gro, each of

whom has published short stories, novellas, and novels in the last few decades. Gaitskill and Gro

work dierently in each form, even if the forms resemble each other in style and/or content. It’s hard

to imagine “Tiny, Smiling Daddy” (1997) as a novel or Fates and Furies (2015) as a short story; the

ending of the former would be muted if it came after hundreds of pages, and the latter could not be

compressed into twenty pages without losing a great deal. It may seem as though I’m presenting a

9

Clouther: Rethinking Length and Form in Fiction

Published by RIT Scholar Works, 2023

Journal of Creative Writing Studies 10

straw man—who, after all, claims that short stories are the same as novels?—but when instructors

ask students to translate novels and novellas into short story form, instructors privilege the length

of the short story, including the way elements such as pace and characterization are executed in that

form as opposed to other forms.

I give students who want to workshop novels or novellas two options: 1) Submit a novel or

novella excerpt as a stand-alone piece that’s workshopped on its own terms (à la Egan’s “Safari”),

or 2) Submit a novel or novella excerpt with a one-page synopsis. In The Business of Being a

Writer (2018), Jane Friedman wrote that the synopsis has to accomplish the following three things:

First, you need to tell us what characters we’ll care about, including the protagonist, and convey

their story. Generally you’ll write the synopsis with your protagonist as the focus, and show

what’s at stake for them.

Second, we need a clear idea of the core conict for the protagonist, what’s driving that conict,

and how the protagonist succeeds or fails in dealing with it.

Finally, we need to understand how the conict is resolved and how the protagonist’s situation,

both internally and externally, has changed. (115)

Friedman’s audience for the synopsis isn’t workshop participants but editors, and her under-

standing of a novel’s shape is conventional: a protagonist with a conict and a conict that’s

resolved, revealing a change in the protagonist. Writers attempting something more experimental

or writers who don’t know what shape their novel will take may resist this document.

But resistance might be the norm for the synopsis, which possesses none of the glory of the

novel. Indeed, Friedman suggested that the synopsis “may be the single most despised document

that novelists—and some narrative nonction writers—are asked to prepare” (114). Accordingly,

I’m not fussy about what the synopsis looks like. I nd that taking the time to outline a novel

or novella is useful for the writer, no matter how frustrating the process, and that readers are

grateful to have a guide, no matter how imperfect. Writers and readers recognize that manu-

scripts change in the writing and that no synopsis is xed. The goal isn’t to provide a crystal ball.

The goal is to situate the novel or novella excerpt in a larger framework. Absent this framework,

workshops can become rudderless with participants deferential to what the writer may do or may

have done already.

Then there is the question of whether graduate students, let alone undergraduate students,

should workshop novels or novellas in the rst place. It’s a question worth considering, as the stakes

are high: a short story is likely to take weeks or months to write, but a novel is likely to take years.

10

Journal of Creative Writing Studies, Vol. 8, Iss. 1 [2023], Art. 8

https://scholarworks.rit.edu/jcws/vol8/iss1/8

Rethinking Length and Form in Fiction 11

Isn’t it deleterious to a writer’s development to commit herself to a long project before she’s sure of

what she wants to say and how she wants to say it?

Maybe. I wouldn’t direct an ambivalent student toward the novel; I would encourage that student

to work with a short form instead before committing herself to a long one. The experience of writing

several short stories and revising some, though not all, of the short stories is good practice for a

beginning ction writer. But many students arrive to workshop having already done some of this

work. Students who grew up with social media and/or online forums have practiced writing for an

audience and receiving feedback in the form of comments or even likes. These students often have

a sophisticated sense of what they want to say and how they want to say it. Sometimes I have under-

graduates who have already written and shared novels. That these students have worked on their

craft and sought peer review outside of an academic setting is something to celebrate, not ignore.

Some students arrive to the UNO MFA in Writing having already published books. Telling these

students—who, as a rule, are pursuing the low-residency program in addition to managing their

careers and/or families—that they have to write short stories because the workshop model is built for

short stories would be absurd. Workshops should support students, not the other way around.

When I work with both undergraduate and graduate students, I’m frank about the risks of

writing a novel. Most people don’t publish the rst novel they write. Students may have to write a

novel or several novels before they achieve a nished product that interests readers, let alone agents

or editors. Although the risks of writing a novel are high, the rewards are also high. The majority of

agents and editors are looking for novels, not short stories. If students want to write novels, and the

literary marketplace wants to read novels, then program directors should consider how their work-

shops encourage these desires rather than squash them.

In “Creativity and the Marketplace,” a chapter of The Creativity Market: Creative Writing in the

21st Century (2012), Jen Webb called for a pedagogical approach that

allows teachers, students and graduates a space in which to consider what we do when we

make creative work as professionals, and what we do when we employ the processes of creative

thinking and practice to generate objects of benet to ourselves as practitioners (the private

sector) and to society more broadly (the public sector). (50)

In Webb’s view, “creative objects, in general, and novels, in particular, can create public spaces

– spaces for conversation, discussion, argument, reection and exchange” (50).

Some creative writing programs discourage discussion of publication, preferring to focus

exclusively on the artistic merits of the work. But if publication is a goal for the workshop—and

it is for many upper-level undergraduate and graduate students—then it’s appropriate to explore

11

Clouther: Rethinking Length and Form in Fiction

Published by RIT Scholar Works, 2023

Journal of Creative Writing Studies 12

submitting to independent and university presses, as well as contests. Depending on the size of

the class, workshopping query letters to agents and/or novel synopses may prove a valuable use

of class time, though I wait until students have rst had their ction workshopped.

If it seems as though I’ve discussed novels more than novellas, that’s because I’ve found that

students are much more interested in novels. Although university presses such as Miami Uni-

versity Press and Texas Review Press award annual novella prizes, the market for the novella

is considerably smaller than the market for the novel. As a graduate student, I took a novella

workshop with Ethan Canin, who by that point had published short stories, novels, and—most

unusual to me—four novellas in The Palace Thief (1994), one of which was adapted into the

2002 lm The Emperor’s Club. Canin’s workshop had a simple structure that graduate—and

perhaps undergraduate—workshops can replicate if class sizes are small enough: one novella per

week. In a sixteen-week semester with fteen students, this means a lot of reading but not too

much, provided novellas are limited to a certain length (e.g. 30,000 words). These workshops may

demand more vigilant facilitation from the instructor than workshops of short stories or novel/

novella excerpts, lest students discuss only a portion of the pages submitted.

3. WORKSHOPPING FLASH

The brevity of ash makes it, in certain regards, ideal for ction workshops. For many

students, especially beginning students, the length of ash feels less daunting. For courses with

large class sizes and/or limited time, including workshops outside of colleges and universities,

ash allows instructors to workshop more students in fewer sessions.

Instructors should clarify both length and number in advance. Flash is commonly considered

to have fewer than 750 or 1,000 words. Many print and online journals allow writers to include

up to three ash pieces with each submission (writers will discover publishing opportunities for

ash that don’t exist for longer forms, in part because ash takes up less space). These are useful

guidelines, but they aren’t absolute.

In a 2021 presentation collected in the Journal of Creative Writing Studies, Emily Capettini

highlighted how workshopping ash benets students familiar with workshopping short stories:

Teaching ash ction within the short story workshop has created opportunities for students

to be more purposeful and thoughtful about things like word choice, narrative structure and

focus, use of constraint, or techniques like load-bearing sentences. While these techniques are

often part of the short story craft, because ash ction is brand new to a lot of students, practic-

ing ash ction creates an opportunity for students to go back to these basics of their craft and

knock out the drywall and see what else is hidden.

12

Journal of Creative Writing Studies, Vol. 8, Iss. 1 [2023], Art. 8

https://scholarworks.rit.edu/jcws/vol8/iss1/8

Rethinking Length and Form in Fiction 13

I like the idea that writing ash leads students, especially those unfamiliar with the form,

to be deliberate with literary techniques, though I don’t assume that students will move in this

direction without guidance. I assign published ash and dedicate time in class to discussing sim-

ilarities to and dierences from longer forms. I ask the straightforward question: is ash best

understood as a short short story?

I’m not convinced myself, even if the label “short short story” was used regularly in the past

and is still used sometimes today. Although I compare forms in class, it can be more reductive than

illuminating to dene one form in direct relation to another. Consider the rst denition in the

Oxford English Dictionary for “novella”: “Originally: a short ctitious narrative. Now (usually): a

short novel, a long short story.” What a lot of work that comma is asked to do. It seems to signal an

appositive, but I’ll argue instead for a continuum, locating the novella between the short story and

the novel. On the same continuum, I place ash rst, before the short story.

Since I don’t dene ash in relation to the short story, I don’t insist that writers practice writing

short stories before writing ash. Some examples of ash are startlingly short, bearing a faint

resemblance to the short story. Joyce Carol Oates’s “The Widow’s First Year” (2011) consists of four

words: “I kept myself alive” (63). Deb Olin Unferth’s “Likable” (2012) has a lot to say about age

and gender in 334 words. Then there is Lydia Davis, who may be ash’s best-known contemporary

practitioner. The Collected Stories of Lydia Davis (2009) and Can’t and Won’t: Stories (2014) oer a

master class of the form, one that sometimes looks like a short story but often does not.

In The Rose Metal Press Field Guide to Writing Flash Fiction: Tips from Editors, Teachers, and

Writers in the Field (2009), Jayne Anne Phillips, one of the “Kmart realists,” shared that she taught

herself to write with “one-page ctions”:

I found in the form the density I needed, the attention to the line, the syllable. I began writing

as a poet. In the one-page form, I found the freedom of the paragraph. I learned to understand

the paragraph as secretive and subversive. The poem in broken lines announces itself as a

poem, but the paragraph seems innocent, workaday, invisible. The paragraph is simply the form

of written information: instruction booklets, tax forms, newspapers, cookbooks: all are written

in paragraphs. We read the lines; the words enter us. (36-37)

The relationship between writer and reader shows up regularly in discussions of ash, perhaps

because that relationship can feel more intimate in a shorter form. In this way, ash is similar to the

present tense, which trades the temporal range of the past tense for immediacy.

In Flash Fiction Forward: 80 Very Short Stories (2006), James Thomas and Robert Shapard

suggested two parameters for ash: “rst that the subject of a ash should not be small, or trivial,

13

Clouther: Rethinking Length and Form in Fiction

Published by RIT Scholar Works, 2023

Journal of Creative Writing Studies 14

any more than it should for a poem, and second that the essence of a story (including its ‘true

subject’) exists not just in the amount of ink on the page—the length—but in the writer’s mind,

and subsequently the reader’s” (12-13). Teaching ash, I emphasize that smallness of form should

suggest neither smallness of subject nor ambition. I articulate Thomas and Shapard’s second point

in terms of trust: the writer trusts her prose to communicate meaning, and the writer trusts her

reader to make meaning.

Workshopping multiple ash pieces in one session requires establishing explicit guide-

lines. Both participants and the author will want to know in advance how time will be allocated.

Instructors may dedicate the same amount of time for each piece (e.g. twenty minutes per ash

in an hour-long workshop) or allow participants to determine which pieces warrant greater atten-

tion, which is riskier but potentially more helpful. If instructors aren’t clear upfront, then the

workshop is likely to suer. Many participants have experienced the frustration of listening to a

fellow participant itemize minor issues of diction or punctuation that easily could have been left

as line edits. More frustrating is running out of time before a piece has been workshopped at all.

Flash lends itself to experimentation, perhaps because it’s considered a newer form and thus less

indebted to tradition. The dierence between ash and prose poems is a voluble source of disagree-

ment, but in a ction workshop, I’m unconcerned with this distinction. I’m committed to creating a

space where students feel comfortable trying dierent things, including work unlike anything else

students have seen. Introducing and maintaining such a space is the subject of the next section.

4. WORKSHOPPING HYBRID

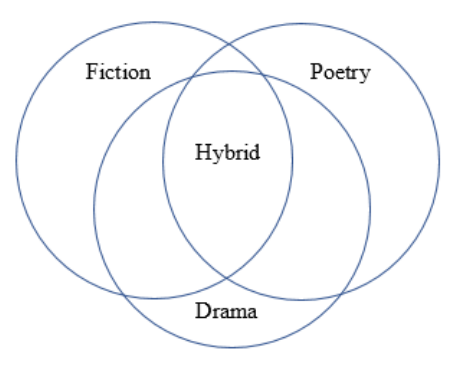

Whereas I presented length as a continuum in the previous section (i.e. ash-short story-novella-

novel), I’ll use Venn diagrams to present hybrid forms. Consider a work, such as F. Scott Fitzger-

ald’s This Side of Paradise (1920), that liberally employs elements of ction, poetry, and drama:

Figure 1.

14

Journal of Creative Writing Studies, Vol. 8, Iss. 1 [2023], Art. 8

https://scholarworks.rit.edu/jcws/vol8/iss1/8

Rethinking Length and Form in Fiction 15

This Side of Paradise was sold as a novel, and that’s how the book is classied today. But This

Side of Paradise doesn’t much resemble the structures of Fitzgerald’s better-known novels, The Great

Gatsby (1925) and Tender is the Night (1934). Fitzgerald interspersed verse throughout This Side of

Paradise, and much of the middle section reads as a play. How would this text be workshopped today?

Based on the ction workshops I’ve attended: uneasily. Participants might oer the following

questions about Fitzgerald’s submission: Why did the author start including poems (11)? Are these

poems good—are they supposed to be? What’s happening with “Interlude”—sometimes it’s a letter,

and sometimes it’s a poem (117-121)? The novel turns into a play with “The Débutante”—doesn’t

that happen pretty late (123-146)? Why does the play turn back into a novel?

Other workshop participants might announce that they’re unqualied for the job. Presented

unexpectedly with verse, students can turn shy, as if line breaks rendered the words unintelligible.

I appreciate these students’ hesitancy, which I read as goodwill. Each of the workshop models I’ve

described to this point has at least one central tenet in common: it’s grounded in criticism. In such

an environment, it’s reasonable that students would point to places where they don’t feel equipped

to weigh in, lest they do more harm than good or seem like know-it-alls.

On the other hand: writers need to teach readers how to read each new piece of ction, regard-

less of form. Writers and readers share language—to an extent—but characters, actions, conicts,

etc. start with the writer. If the reader doesn’t care about whom she’s watching or what that person

is doing or why that person is doing that thing, then the reader will nd another way to spend her

time. In a ction workshop, participants needn’t be poets or playwrights to read a manuscript that

includes verse or drama. I encourage students who are hesitant when encountering hybrid works to

focus on the areas where they believe they can help the author and stay respectfully quiet elsewhere.

A discussion of setting in a ash piece may be no dierent from a discussion of setting in a short

story or novel excerpt. How does or doesn’t the writer succeed at bringing the reader into the place?

On the other other hand: students are often less concerned with distinctions in form than

instructors are. At the undergraduate level, there’s a good chance that students in a ction workshop

have already taken, or are currently taking, a poetry or creative nonction (CNF) or screenwriting

workshop. Hybrid forms allow students to apply what they’ve learned—or are actively learning—in

a dierent context, which is precisely what a liberal arts education ought to do.

The writer shouldn’t expect participants in a ction workshop to oer critiques of meter or

stage directions. Fortunately, I’ve never known an author to expect anything like this. Mostly, I’ve

received gratitude for not ending a workshop before it has a chance to begin.

15

Clouther: Rethinking Length and Form in Fiction

Published by RIT Scholar Works, 2023

Journal of Creative Writing Studies 16

There are submissions I’ve vetoed. I remember a graduate student who wanted to submit a

hybrid piece for a prose workshop. The piece included more pages of poetry and photography

than prose, and I worried that the author would receive tentative feedback. Now I’m not con-

vinced I made the right decision. The author’s condence may have been more undermined by my

request for a new submission than from a meandering workshop of the original submission. The

workshop participants, for that matter, might have risen to the occasion. There is a point, I think,

where a piece no longer ts under the umbrella of ction, where it turns into something else, and

that piece may be no more suitable for a ction workshop than a painting or a dance performance.

It’s dicult to maintain useful guidelines, however, if you’re unwilling to test them.

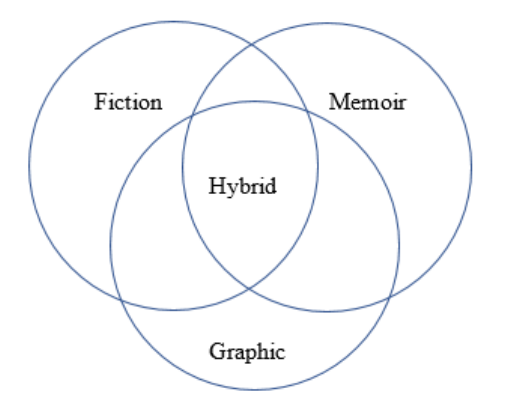

Consider another hybrid work, Neela Vaswani’s You Have Given Me a Country: A Memoir

(2010), which blends ction with memoir and graphic:

The overlap between ction and memoir is an area my students generally feel comfortable

exploring and critiquing; it’s not unusual in the UNO MFA in Writing to have students enter in CNF

and migrate to ction (CNF and ction students workshop together as prose). You Have Given Me a

Country announces itself as nonction in the title yet begins: “What follows is real, and imagined”

(Vaswani viii). The interplay between fact and ction and between text and image (the rst image

appears on page three) teaches readers how to understand the hybridity of the work, which explores

the dierent identities that Vaswani lived as a biracial child with an Indian-born father and Amer-

ican-born mother: “I developed an ability to hold two things in my mind at once. Two feelings,

two ideas, two languages. The in-between, inside me. Like two spotlights on a dark stage, coming

together. And where they overlapped, it was brightest. It was easiest to see” (71-72).

Figure 2.

16

Journal of Creative Writing Studies, Vol. 8, Iss. 1 [2023], Art. 8

https://scholarworks.rit.edu/jcws/vol8/iss1/8

Rethinking Length and Form in Fiction 17

In a 2016 essay in The Writer’s Chronicle, published by the Association of Writers and Writing

Programs, Jacqueline Kolosov suggested that “taken individually but especially in conversation

with one another, literary hybrids illustrate that genres are not xed entities but vehicles for nding

the best form for our stories, memories, and explorations.” I want to use Kolosov’s claim here to

counter the argument that students need to establish themselves in a traditional form before moving

to a hybrid form. One might conceptualize form as a vessel to take the reader somewhere, rather

than as a pattern to replicate. The writer chooses—or creates—the appropriate vessel for each nar-

rative she wishes to tell. In such a formulation, workshop participants might see their task as helping

the writer to nd the best vessel.

If a workshop can accommodate dierent lengths and forms, then it stands to reason that a

workshop can accommodate dierent genres, such as CNF and poetry. Many workshops, especially

introductory ones, do. The creative writing course that I taught as a teaching assistant was designed

this way, as is the creative writing course taught by graduate assistants in the UNO MFA in Writing.

As students progress to intermediate and advanced workshops, workshops typically specialize,

but specialization needn’t exclude hybrid forms. As an instructor and program director, I want to

encourage the unusual and the new.

5. WHY WORKSHOP DIFFERENT LENGTHS AND FORMS?

In the much-discussed essay collection MFA vs NYC: The Two Cultures of American Fiction

(2014), Chad Harbach wrote that the MFA “nudges the writer toward the writing of short stories;

of all the ambient commonplaces about MFA programs, perhaps the only accurate one is that the

programs are organized around the story form” (17). The dierence between creative writing

programs’ focus on the short story and major American publishers’ focus on the novel is the subject

of Harbach’s essay and the impetus for the collection. I won’t dispute the dierence, though I’m

unconvinced it needs to persist.

Which is not to say that colleges and universities should look to the so-called Big Five of

Hachette, HarperCollins, Macmillan, Penguin Random House, and Simon and Schuster to guide

curricula (Penguin Random House and Simon and Schuster recently pursued a merger, which

follows the merger of Penguin and Random House in 2013). MFA programs and big publishers

have dierent goals; the former produces graduates, and the latter produces books. Some gradu-

ates go on to publish books, but many—even at the most high-prole programs—don’t. Other

graduates publish with independent or university presses. Some graduates nd success writing—

and, often, teaching—without publishing with a big press. These graduates don’t dene their

achievement relative to New York City, and the programs that produce and/or employ the gradu-

ates don’t ask them to do so.

17

Clouther: Rethinking Length and Form in Fiction

Published by RIT Scholar Works, 2023

Journal of Creative Writing Studies 18

Nor do major American publishers rely on creative writing programs; these publishers make

most of their money from writers without an MFA. In 2020, the best-selling authors came from

varied sources, such as politics (e.g. Barack and Michelle Obama, Mary L. Trump), anti-rac-

ism (e.g. Robin DiAngelo, Ibram X. Kendi), celebrity (e.g. Matthew McConaughey), and Oprah

Winfrey (e.g. Jeanine Cummins, Isabel Wilkerson). That’s not counting titles for children, includ-

ing workbooks and activity books, which were among the year’s best sellers. The Dog Man and

Diary of a Wimpy Kid empires are arguably more important to the Big Five than the combined

heft of graduate creative writing.

Even if MFA and NYC don’t need each other, they can help each other. As much as creative

writing programs might like to see major American publishers release more short story collections,

it’s likelier that these publishers will market and distribute novels, which sell—with few excep-

tions—far better than short stories. Harbach again: “A writer’s early short stories (as any New York

editor will tell you) lead to a novel, or they lead nowhere at all” (18). Celeste Ng and Brit Bennett

wrote two of the best-selling novels of 2020, each with Penguin Random House (the Penguin and

Riverhead imprints, respectively). Both Ng and Bennett received an MFA from the University of

Michigan, one of the strongest graduate programs in the United States.

A creative writing program that encourages students to workshop forms other than the short

story acknowledges the literary marketplace without surrendering to it. If students want to write and

workshop short stories, as students have been doing productively for decades, then I see no reason

why students should stop. But if they want to write and workshop other forms, then programs can

do more than begrudgingly allow students to do so (if programs even do that).

In a chapter of Does the Writing Workshop Still Work? (2010), “Introducing Masterclasses,” Sue Roe

argued that “agents and publishers – increasingly, in our culture – are not only the best judges of what

will work in current markets, they are also well placed, and usually willing, to point out to a student what

works, what doesn’t and what might be developed” (202). Roe went on to note the following:

However the main distinction between agents and editors is their understandable lack of concern

with students who do not display the necessary credentials or skills to become published writers.

Agents and editors would not be doing their job were they to expend time and energy on projects

they know will not succeed in the market place. Tutors would not be doing theirs were they to

ignore the authors of such projects, privileging the most obviously able. Agents and publishers

should be in universities, talent-spotting and keeping students and sta up to date with market

forces and commercial issues. But the teacher’s responsibility is the painstaking job of teaching

the rudiments, setting reading and exercises tailored to each individual student’s progress; gradu-

ally improving the quality of each and every student’s work. (202)

18

Journal of Creative Writing Studies, Vol. 8, Iss. 1 [2023], Art. 8

https://scholarworks.rit.edu/jcws/vol8/iss1/8

Rethinking Length and Form in Fiction 19

Some creative writing programs dedicate discrete courses to publication (such courses are

beyond the scope of this essay, which takes the ction workshop as its subject), but many programs

don’t provide instruction on traditional publishing, opting to focus on craft rather than professional

practice. Instructors in such programs can still workshop novels by acknowledging Roe’s distinc-

tion between the role of the agent or editor and the role of the teacher.

The teacher might communicate to students early that her mission is not to identify and

develop the most promising projects for sale but to help all students become stronger writers,

focusing on elements of the form as they appear in student and published manuscripts. This

teacher doesn’t ignore the market so much as establish boundaries of what she does and doesn’t

do in the workshop. Time inside any classroom is nite, and teachers benet students by articu-

lating how their time will be spent.

In a 2004 essay in College English, Patrick Bizzaro reviewed the history of workshops, con-

cluding that they oered a “model of instruction over a hundred years old but basically unrevised”:

Clearly, the lore of creative-writing instruction has it that writers should teach what they do

when they write, employing the “workshop” approach to teaching—based on a longstanding

notion that the teacher is a “master” who teaches “apprentices.” The workshop method survives

not because rigorous inquiry oers testimony to its excellence (though, once this research is

done, such inquiry might support exactly that premise), but because only recently have some

teachers of creative writing questioned its underlying assumptions. (296)

I share Bizzaro’s skepticism of workshops not because I haven’t found them useful—I have as

a student, an instructor, and a program director—but because they seem guided more by tradition

than by research or pedagogy. The choice needn’t be between the workshop and a dierent method

of instruction. The choice I’m interested in is between stasis and innovation within the workshop.

I made changes during two years of facilitating online workshops that I’ve brought to face-

to-face workshops. I now, for example, request that students share something they appreciated

or admired about the ash/short story/novella excerpt/novel excerpt/hybrid before we begin cri-

tiquing the piece, a continuation of the structured way that I ask students to participate in online

workshops. At the beginning of these workshops, I place each student’s name in the chat, and all

participants oer something positive about the piece before—in the same order—they oer con-

structive criticism. During the criticism portion, which constitutes the majority of the workshop,

I pause or redirect discussion to moderate a back-and-forth conversation, something dicult to

achieve over videoconference where students are justiably worried about speaking over others.

While this method lacks spontaneity, the process assures that each participant hears her own

19

Clouther: Rethinking Length and Form in Fiction

Published by RIT Scholar Works, 2023

Journal of Creative Writing Studies 20

voice at least twice while removing the pressure that many students feel to speak only if they

have something important to say (for some students, such discretion is helpful, but for too many,

it means they rarely if ever speak).

When I discovered that my online workshops were eliciting insightful participation from

students who had been quiet in face-to-face workshops, I adjusted those workshops accordingly.

My face-to-face workshops today are a blend of structured and free-owing discussion; some

participants speak more than others, but all contribute. Although I have returned to face-to-

face workshops, I still oer workshops by videoconference. Online workshops are able to reach

writers who live in dierent places and/or with circumstances that make it dicult or impossible

to attend a face-to-face workshop, including some people with disabilities. I hope that program

directors take advantage of the disruption to the status quo occasioned by COVID-19. The post-

pandemic workshop shouldn’t rush to return to normal. It presents an opportunity for further

introspection and experimentation.

20

Journal of Creative Writing Studies, Vol. 8, Iss. 1 [2023], Art. 8

https://scholarworks.rit.edu/jcws/vol8/iss1/8

Rethinking Length and Form in Fiction 21

Works Cited

Aristotle. Poetics. Translated by S. H. Butcher, Dover Publications, 1997.

Bizzaro, Patrick. “Research and Reection in English Studies: The Special Case of Creative Writing.” College

English, vol. 66, no. 3, 2004, pp. 294–309.

Capettini, Emily. “‘But How Do You Write It?’: Teaching Flash Fiction in the Short Story Workshop.” Journal

of Creative Writing Studies, vol. 6, iss. 1, article 34, 2021. https://scholarworks.rit.edu/jcws/vol6/

iss1/34. Accessed 1 May 2021.

Chang, Lan Samantha. “Writers, Protect Your Inner Life.” Literary Hub https://lithub.com/writers-protect-your-

inner-life/. Accessed 24 Apr. 2021.

Chavez, Felicia Rose. The Anti-Racist Writing Workshop: How To Decolonize the Creative Classroom.

Haymarket Books, 2021.

Clark, Miriam Marty. “Contemporary Short Fiction and the Postmodern Condition.” Studies in Short Fiction,

vol. 32, no. 2, 1995, pp. 147-159.

Fitzgerald, F. Scott. This Side of Paradise. Dover Publications, 1996.

Friedman, Jane. The Business of Being a Writer. Chicago UP, 2018.

Harbach, Chad. “MFA vs NYC.” MFA vs NYC: The Two Cultures of American Fiction, edited by Chad

Harbach, Faber and Faber, 2014, pp. 9-28.

Hills, Rust. Writing in General and the Short Story in Particular. Mariner Books, 2000.

Kolosov, Jacqueline. “Finding the Right Form: Exploring and Experimenting with Hybrid Literary Genres.”

The Writer’s Chronicle, Feb. 2016, https://www.awpwriter.org/magazine_media/writers_chronicle_

view/3930/nding_the_right_form_exploring_and_experimenting_with_hybrid_literary_genres.

Accessed 8 May 2021.

Lerman, Liz. “Critical Response Process.” https://lizlerman.com/critical-response-process/. Accessed 21 Apr.

2021.

“Novella.” Oxford English Dictionary. 3rd ed. 2019.

Oates, Joyce Carol. “The Widow’s First Year.” hint ction: An Anthology of Stories in 25 Words or Fewer,

edited by Robert Swartwood, W. W. Norton and Company, 2011, p. 63.

Phillips, Jayne Anne. “‘Cheers,’ (or) How I Taught Myself to Write.” The Rose Metal Press Field Guide to

Writing Flash Fiction: Tips from Editors, Teachers, and Writers in the Field, edited by Tara L. Marsh,

Rose Metal Press, 2009, pp. 36-40.

Roe, Susan. “Introducing Masterclasses.” Does the Writing Workshop Still Work?, edited by Dianne Donnelly,

Multilingual Matters, 2010, pp. 194-205.

Saunders, George. A Swim in a Pond in the Rain: In Which Four Russians Give a Master Class on Writing,

Reading, and Life. Random House, 2021.

“The Story Prize.” http://thestoryprize.org. Accessed 16 Apr. 2021.

Thomas, James, and Robert Shapard. “Editors’ Note.” Flash Fiction Forward: 80 Very Short Stories, edited by

James Thomas and Robert Shapard, W. W. Norton and Company, 2006, pp. 11-14.

Vaswani, Neela. You Have Given Me a Country: A Memoir, Sarabande Books, 2010.

Webb, Jen. “Creativity and the Marketplace.” The Creativity Market: Creative Writing in the 21st Century,

edited by Dominique Hecq, Multilingual Matters, 2012, pp. 40-53.

21

Clouther: Rethinking Length and Form in Fiction

Published by RIT Scholar Works, 2023