California Air Resources Board

Public Hearing to Consider the Proposed Amendments to the Low

Carbon Fuel Standard

Staff Report: Initial Statement of Reasons

Date of Release: December 19, 2023

Scheduled for Consideration:

March 21, 2024

This report has been reviewed by the staff of the California Air Resources Board and approved

for publication. Approval does not signify that the contents necessarily reflect the views and

policies of the California Air Resources Board, nor does mention of trade names or commercial

products constitute endorsement or recommendation for use.

0

Table of Contents

Public Hearing to Consider the Proposed Amendments to the Low Carbon Fuel Standard ...... 0

Staff Report: Initial Statement of Reasons ................................................................................. 0

Executive Summary ............................................................................................................... 4

I. Introduction and Background .............................................................................................. 6

Overview of the Low Carbon Fuel Standard ..................................................................... 10

History and Current Status of the Low Carbon Fuel Standard .......................................... 13

Overview of the Proposed Amendments .......................................................................... 17

II. The Problem that the Proposal is Intended to Address .................................................... 22

Strengthen the Annual Carbon Intensity Benchmarks Pre- and Post-2030 ...................... 22

Eliminate Exemption for Intrastate Fossil Jet Fuel ............................................................ 26

Expand Zero Emission Vehicle Infrastructure Crediting ................................................... 27

Biomethane Crediting ....................................................................................................... 29

Project-Based Crediting .................................................................................................... 31

Crop-Based Biofuels Sustainability Criteria ...................................................................... 32

Other Proposed Amendments .......................................................................................... 33

III. The Specific Purpose and Rationale of Each Adoption, Amendment, or Repeal ............ 37

IV. Benefits Anticipated from the Regulatory Action, Including the Benefits or Goals Provided

in the Authorizing Statute ..................................................................................................... 38

Summary of Emission Benefits ......................................................................................... 38

Greenhouse Gas Reduction Benefit - Social Cost of Carbon ........................................... 39

Health Benefits ................................................................................................................. 43

Benefits to Typical California Businesses ......................................................................... 52

Benefits to Small Businesses ........................................................................................... 53

V. Air Quality ........................................................................................................................ 54

Baseline Assumptions ...................................................................................................... 54

Total Emissions Benefits .................................................................................................. 55

VI. Environmental Impact Analysis ....................................................................................... 60

VII. Environmental Justice .................................................................................................... 64

1

Uplifting Equity ................................................................................................................. 65

Conclusion ........................................................................................................................ 67

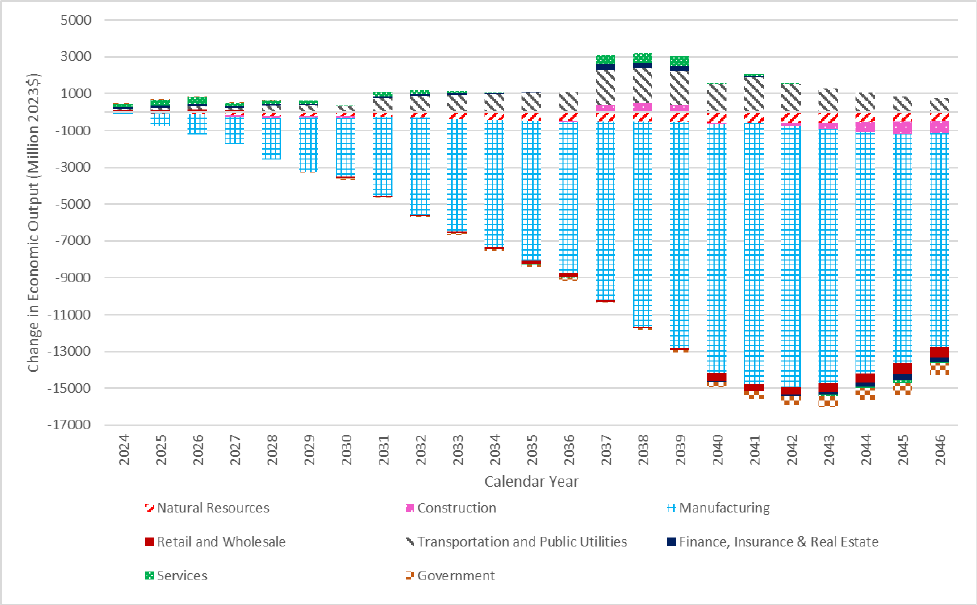

VIII. Standardized Regulatory Impact Analysis .................................................................... 69

Changes Since the Release of the Standardized Regulatory Impact Assessment ........... 69

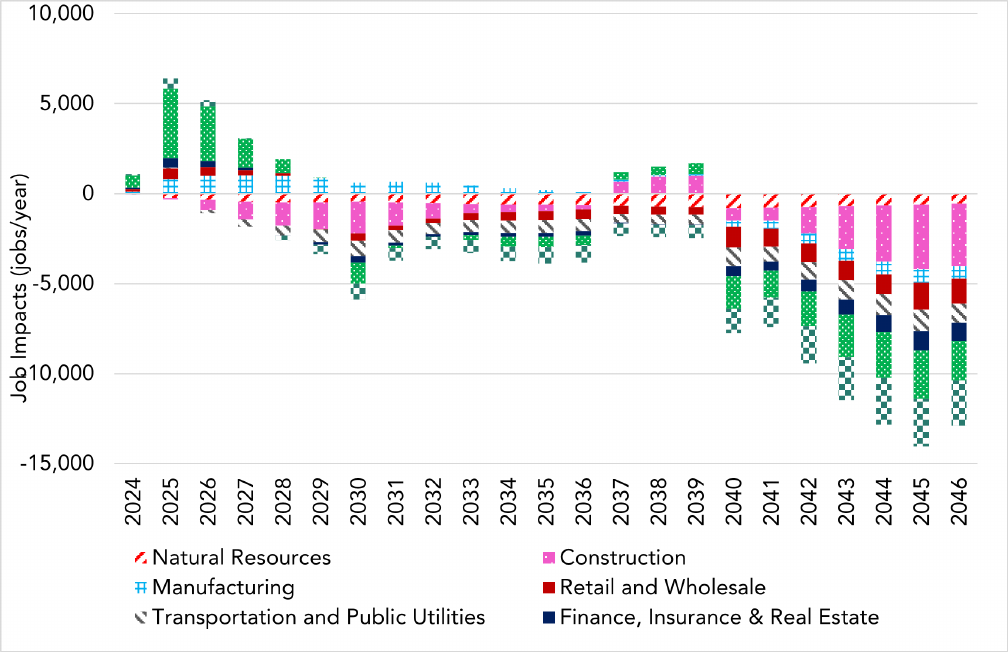

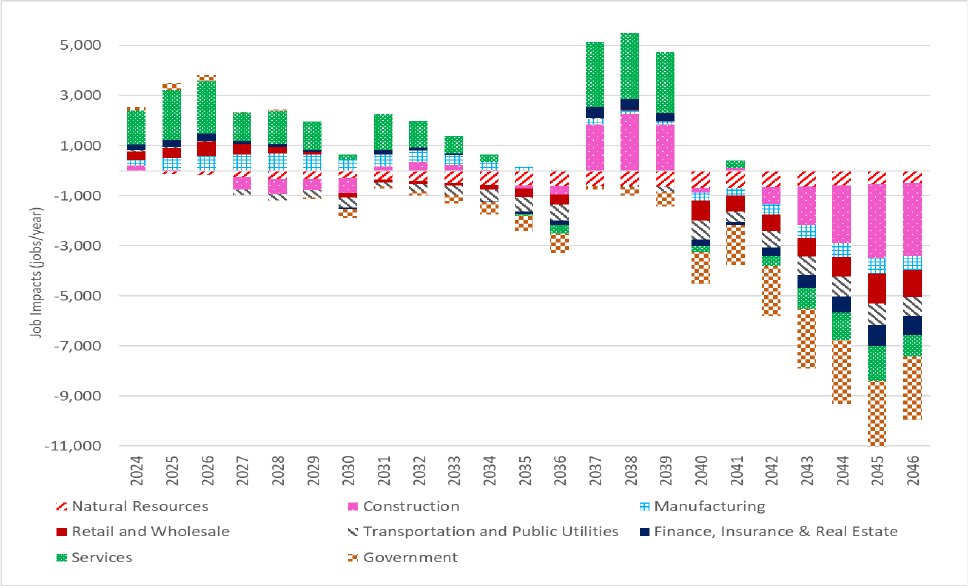

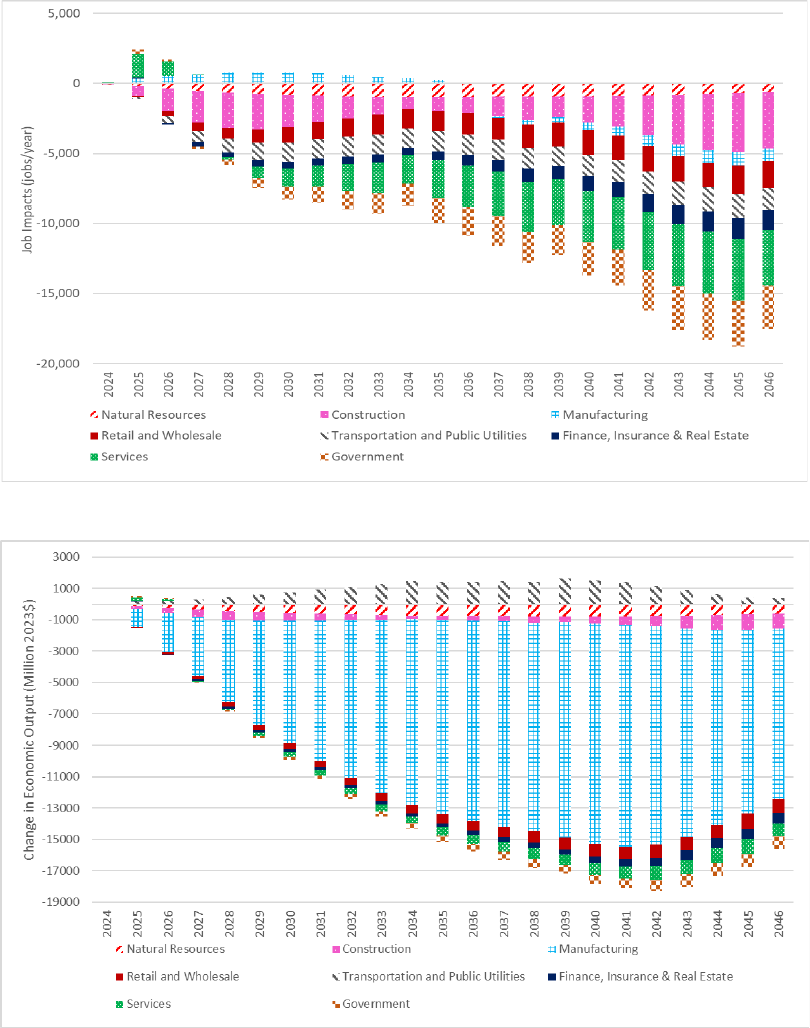

The creation or elimination of jobs within the State of California. ..................................... 71

The creation of new business or the elimination of existing businesses within the State of

California. ......................................................................................................................... 74

The expansion of businesses currently doing business within the State of California. ..... 75

Significant Statewide Adverse Economic Impact Directly Affecting Business, Including

Ability to Compete ............................................................................................................ 78

The competitive advantages or disadvantages for businesses currently doing business

within the State ................................................................................................................. 78

The increase or decrease of investment in the state ........................................................ 80

The incentives for innovation in products, materials, or processes .................................. 81

The benefits of the regulation to the health and welfare of California residents, worker

safety, and the state’s environment. ................................................................................. 82

IX. Evaluation of Regulatory Alternatives ............................................................................. 85

Alternatives to the Regulation ........................................................................................... 85

Other Concepts .............................................................................................................. 115

Small Business Alternative ............................................................................................. 128

Performance Standards in Place of Prescriptive Standards ........................................... 128

Health and Safety Code section 57005 Major Regulation Alternatives........................... 128

X. Justification for Adoption of Regulations Different from Federal Regulations Contained in

the Code of Federal Regulations ....................................................................................... 129

XI. Public Process for Development of the Proposed Action (Pre-Regulatory Information) 131

XII. References .................................................................................................................. 135

XIII. Appendices ................................................................................................................. 143

2

List of Acronyms and Abbreviations

2022 Scoping Plan Update 2022 Scoping Plan for Achieving Carbon Neutrality

AAM Automatic Acceleration Mechanism

AB Assembly Bill

ACC II Advanced Clean Cars II

ACF Advanced Clean Fleets

ACT Advanced Clean Trucks

AFP Alternative Fuels Portal

AFPR Annual Fuel Pathway Report

AJF Alternative Jet Fuel

Btu British Thermal Units

CA-GREET California Greenhouse Gases, Regulated Emissions, and

Energy Use in Transportation

CARB or Board California Air Resources Board

CARBOB California Reformulated Gasoline Blendstocks for Oxygenate

Blending

CATS California Transportation Supply Model

CCM Credit Clearance Market

CCS Carbon Capture and Sequestration

CEQA California Environmental Quality Act

CHC Commercial Harbor Craft

CI Carbon Intensity

CH

4

Methane

CNG Compressed Natural Gas

CO

2

Carbon Dioxide

Court State of California Court of Appeal, Fifth Appellate District

DAC Direct Air Capture

DC Direct Current

EIA Environmental Impact Analysis

EER Energy Economy Ratio

eCHE Electric Cargo Handling Equipment

ED Emergency Department

EJ Environmental Justice

EJAC Environmental Justice Advisory Committee

eGRID Emissions & Generation Resource Integrated Database

EMFAC Emissions FACtor Model

eOGV Electric Power for Ocean-going Vessel

eTRU Electric Transport Refrigeration Units

EV Electric Vehicle

FCI Fast Charging Infrastructure

FCV Fuel Cell Vehicle

FSE Fuel Supply Equipment

gCO

2

e/MJ Grams of CO

2

equivalent per megajoule

GHG Greenhouse Gas

HEFA Hydroprocessed Ester and Fatty Acid

HRI Hydrogen Refueling Infrastructure

HyCAP Hydrogen Capacity Model

3

HySCapE Hydrogen Station Capacity Evaluation Model

ICT Innovative Clean Transit

IRA Inflation Reduction Act

ISOR Initial Statement of Reasons

IWG Interagency Working Group on the Social Cost of

Greenhouse Gases

kW Kilowatt

LCA Life Cycle Analysis

LCFS Low Carbon Fuel Standard

LC/LEU Low-Complexity/Low-Energy-Use

L-CNG Liquified Compressed Natural Gas

LD Light-Duty

LDV Light-Duty Vehicle

LRT-CBTS LCFS Reporting Tool and Credit Bank & Transfer System

LUT Lookup Table

MFR Multi-Family Residence

MHD Medium- and Heavy-Duty

MHDV Medium- and Heavy-Duty Vehicle

MW Megawatt

MTCO

2

e Metric tons in carbon dioxide equivalent

NEVI National Electric Vehicle Infrastructure Formula Program

N

2

O Nitrous Oxide

NOx Oxides of Nitrogen

NREL National Renewable Energy Laboratory

OPGEE Oil Production Greenhouse Gas Emission Estimator

PM2.5 Fine Particulate Matter

RFS Renewable Fuel Standard

RNG Renewable Natural Gas

RPS Renewable Portfolio Standard

SAF Sustainable Aviation Fuel

SB Senate Bill

SC-CO

2

Social Cost of Carbon

SFAP Sustainable Freight Action Plan

SLCP Short-Lived Climate Pollutant

ULSD Ultra Low Sulfur Diesel

U.S. EPA United State Environmental Protection Agency

VMT Vehicle Miles Traveled

ZEV Zero-Emission Vehicle

4

Executive Summary

California is the midst of a rapid transition to cleaner fuels and carbon neutrality, with just over

20 years to transition from today’s significant fossil fuel usage to a future of clean fuels and

technology. In 2022, the California Air Resources Board (CARB) approved the 2022 Scoping

Plan for Achieving Carbon Neutrality (2022 Scoping Plan Update), which charted a path to

achieving carbon neutrality by 2045 and reducing greenhouse gas emissions 85% below 1990

levels by 2045. Meeting this goal will require the deployment of greenhouse gas (GHG)

emission reduction strategies at an unprecedented scale and pace.

Many of the strategies identified in the 2022 Scoping Plan Update to address climate change

and achieve carbon neutrality are the same strategies needed to drastically improve air quality.

As transportation emissions, primarily from the use of fossil fuels, are California’s single

biggest source of greenhouse gas emissions and contributor to poor air quality, the State is

working to rapidly increase the numbers of zero-emission vehicles on the road and deploy

cleaner fuels to power them. If California is successful in meeting the clean fuel and vehicle

goals identified in the 2022 Scoping Plan Update, we will reduce fossil fuel demand by 94% by

2045. CARB has already taken significant steps to reducing transportation emissions by

adopting regulations such as Advanced Clean Cars II, Advanced Clean Fleets, Advanced

Clean Trucks, Innovative Clean Transit, and other rules that promote and accelerate the

deployment of low and zero-emission technologies.

The Low Carbon Fuel Standard (LCFS) is a key part of California’s transportation

decarbonization strategy and a successful one thus far. The LCFS provides the economic

incentives to produce cleaner fuels like electricity, hydrogen and biofuels that are needed to

displace fossil fuels and reduce transportation sector emissions. The LCFS has supported the

displacement of billions of gallons of petroleum fuels with lower carbon alternatives, and

without these alternative fuels the State risks returning to higher levels of fossil fuel use and

fewer climate and air quality benefits. With clear scientific consensus on the need to rapidly

decarbonize and achieve carbon neutrality by mid-century, the significant health and economic

benefits of phasing down fossil fuel use, and the introduction of federal funding for alternative

fuels and clean energy, now is the time to update and strengthen the LCFS regulation. This

regulatory update proposal, which is described in detail in this staff report, is focused on the

following key concepts:

• Increasing the stringency of the program to reduce emissions and decarbonize the

transportation fuel sector, which will also aggressively reduce our dependence on fossil

fuels;

• Strengthening the program’s equity provisions to promote investment in disadvantaged,

low-income and rural communities;

• Supporting electric and hydrogen truck refueling;

• Incentivizing more production of clean fuels needed in the future, such as low-carbon

hydrogen;

• Supporting methane emissions reductions and deploying biomethane for best uses

across transportation; and

• Strengthening guardrails on crop-based fuels to prevent deforestation or other potential

adverse impacts.

5

These proposed changes, if adopted, would result in significant GHG reductions as well as air

quality, health, and economic benefits across the State. These benefits include:

GHG Reductions

• 90% reduction in carbon intensity of California’s transportation fuels by 2045.

• 558 million metric tons of life cycle CO

2

e reductions from the amendments.

Health Benefits

• Almost $5 billion in total avoided health costs resulting from nearly 4,300 tons of PM2.5

reduction and more than 25,000 tons of NOx reductions.

Economic Benefits

• $128 billion in revenue estimated accruing to California businesses from credit

generation/sales.

• Job growth in the electricity and biofuel sectors as demand for these fuels grows.

• Increases the diversity and competitiveness of transportation fueling options for

California consumers, transitioning supply from just ten fossil fuel refiners to hundreds

of individual biofuel, electricity, and hydrogen producers.

The changes would also help support implementation of California’s world-leading

zero-emission vehicle policies, align with the 2022 Scoping Plan Update, and provide a model

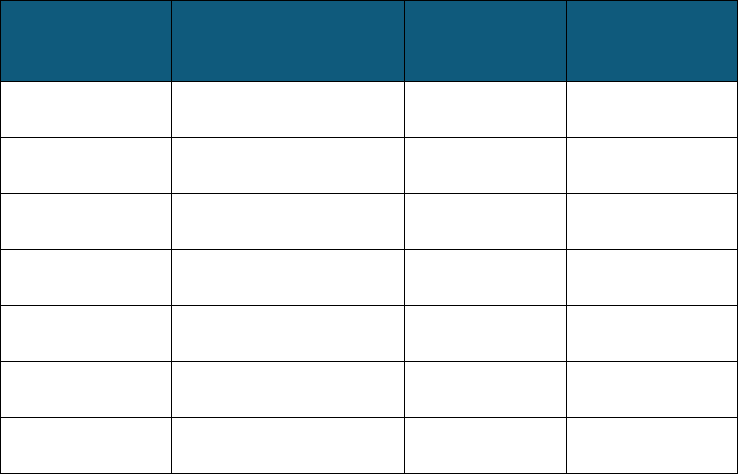

for other jurisdictions looking to deploy clean fuel and climate policies. And finally, as

Californians transition away from less-efficient fossil fuels and into more energy efficient

zero-emission vehicles (ZEVs) and lower-carbon fuel alternatives, the fuel costs Californians

pay to travel would also decrease, providing Californians billions of dollars in savings. CARB

staff estimates the amount of money Californians spend on fueling costs across all vehicle

class could be up to 42% lower in 2045 than compared to fuel costs in 2021. This translates

into an annual savings of over $20 billion in fuel expenditures in 2045 alone.

6

I. Introduction and Background

In this chapter, the California Air Resources Board (CARB or Board) staff provides a brief

overview of the Low Carbon Fuel Standard (LCFS) regulation (California Code of Regulations,

title 17, sections 95480-95503), information on the history and status of the LCFS program,

and an overview of the proposed revisions to the program.

The purpose of the LCFS regulation is to reduce the carbon intensity (CI) of transportation

fuels used in California, thereby reducing GHG emissions, and to incentivize the production of

low-carbon and renewable alternatives, such as low-CI electricity and renewable hydrogen,

and biofuels to displace fossil fuels and allow more energy security in the transportation sector.

It is the most direct tool being deployed to reduce dependence on fossil fuels in the

transportation sector.

The Board approved the LCFS regulation in 2009 as a discrete early action measure under the

California Global Warming Solutions Act of 2006 (Assembly Bill [AB] 32, Núñez and Pavley,

Chapter 488, Statutes of 2006; Healthy and Safety Code sections 38500 et seq.). Since the

passage of AB 32, California has developed bold, creative, and durable policy solutions to

protect our environment and public health. In fact, California met the target established in AB

32—a return of GHG emissions to 1990 levels by 2020—six years ahead of schedule.

Recognizing California’s early successes in achieving GHG emissions reductions and the need

to accelerate climate mitigation efforts, California has continued to enact ambitious goals and

take concrete steps to achieve them. There have been several major new climate statutes

enacted and executive orders issued since the last major LCFS rulemaking in 2018. In 2022,

Governor Gavin Newsom signed several climate bills, including AB 1279 (Muratsuchi, Chapter

337, Statutes of 2022), Senate Bill (SB) 905 (Caballero, Chapter 359, Statutes of 2022), and

SB 1020 (Laird, Chapter 361, Statutes of 2022). AB 1279 requires an 85% reduction in

anthropogenic GHG emissions below 1990 levels by 2045. SB 905 requires CARB to adopt

regulations creating a framework for the development of carbon capture, removal, and storage

projects by 2025. And SB 1020 includes new benchmarks of 90% clean electricity by 2035 and

95% by 2040 ahead of the 100% goal by 2045. A particular focus on the transportation sector

was established through Executive Order N-79-20.

1

Signed in 2020, Executive Order N-79-20

established a State goal that sales of all new passenger vehicles be zero emission by 2035

and that 100% of medium- and heavy-duty vehicles in the State be zero emission by 2045 for

all operations where feasible and by 2035 for drayage trucks. The 2022 Scoping Plan Update,

2

approved by the Board in December 2022, lays out a cost-effective and technologically

feasible path to achieve these targets and achieve carbon neutrality by 2045.

The 2022 Scoping Plan Update signals the need for an aggressive reduction of fossil fuel use,

building on and accelerating greenhouse gas reduction programs that have been in place for a

decade and a half, including the LCFS program. This means rapidly moving to zero-emission

1

State of California Executive Department, Executive Order N-79-20. September 23,

2020. https://www.gov.ca.gov/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/9.23.20-EO-N-79-20-Climate.pdf

2

California Air Resources Board, 2022 Scoping Plan for Achieving Carbon Neutrality. November 16, 2022.

https://ww2.arb.ca.gov/sites/default/files/2022-12/2022-sp_1.pdf

7

transportation; transitioning the cars, buses, trains, and trucks that now constitute California’s

single largest source of planet-warming pollution to zero-emission technology. In the

transportation sector, the transition to complete zero-emission vehicle (ZEV) technology will

not happen overnight.

Achieving GHG emissions of 85% below 1990 levels by 2045 will require significant investment

and use of lower carbon opportunities while zero-emission technologies gain market

penetration and achieve interim climate goals. Conventional internal combustion engine

vehicles from legacy fleets will remain on the road for some time, even after all new vehicle

sales have transitioned to ZEV technology. Therefore, it is necessary to ensure there are

reliable and adequate low-carbon fuel supplies available and continue expansion of low-carbon

fuel production in ways that use existing infrastructure where possible, such as transitioning

refineries to clean fuel production.

3

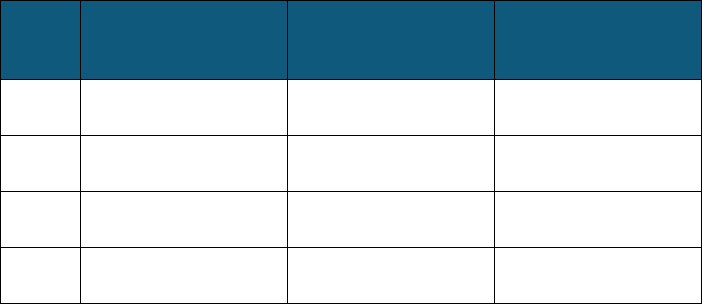

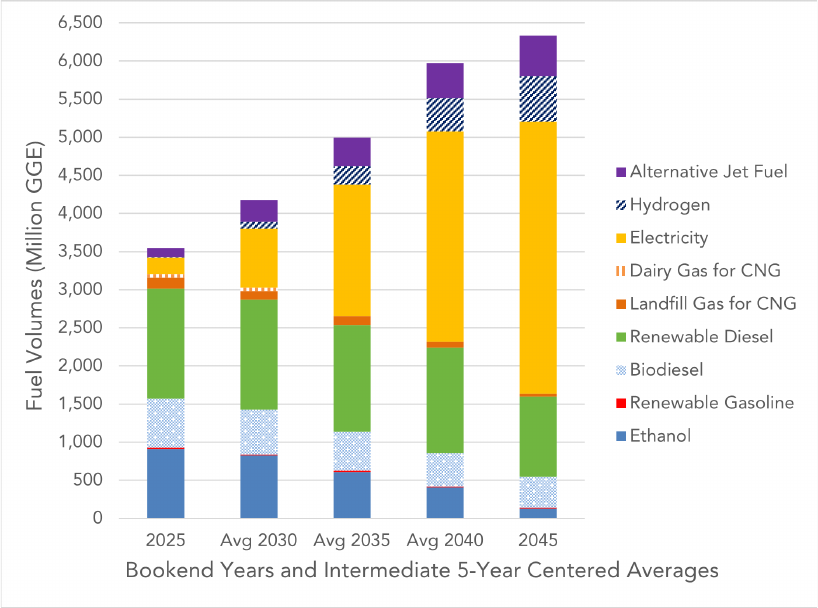

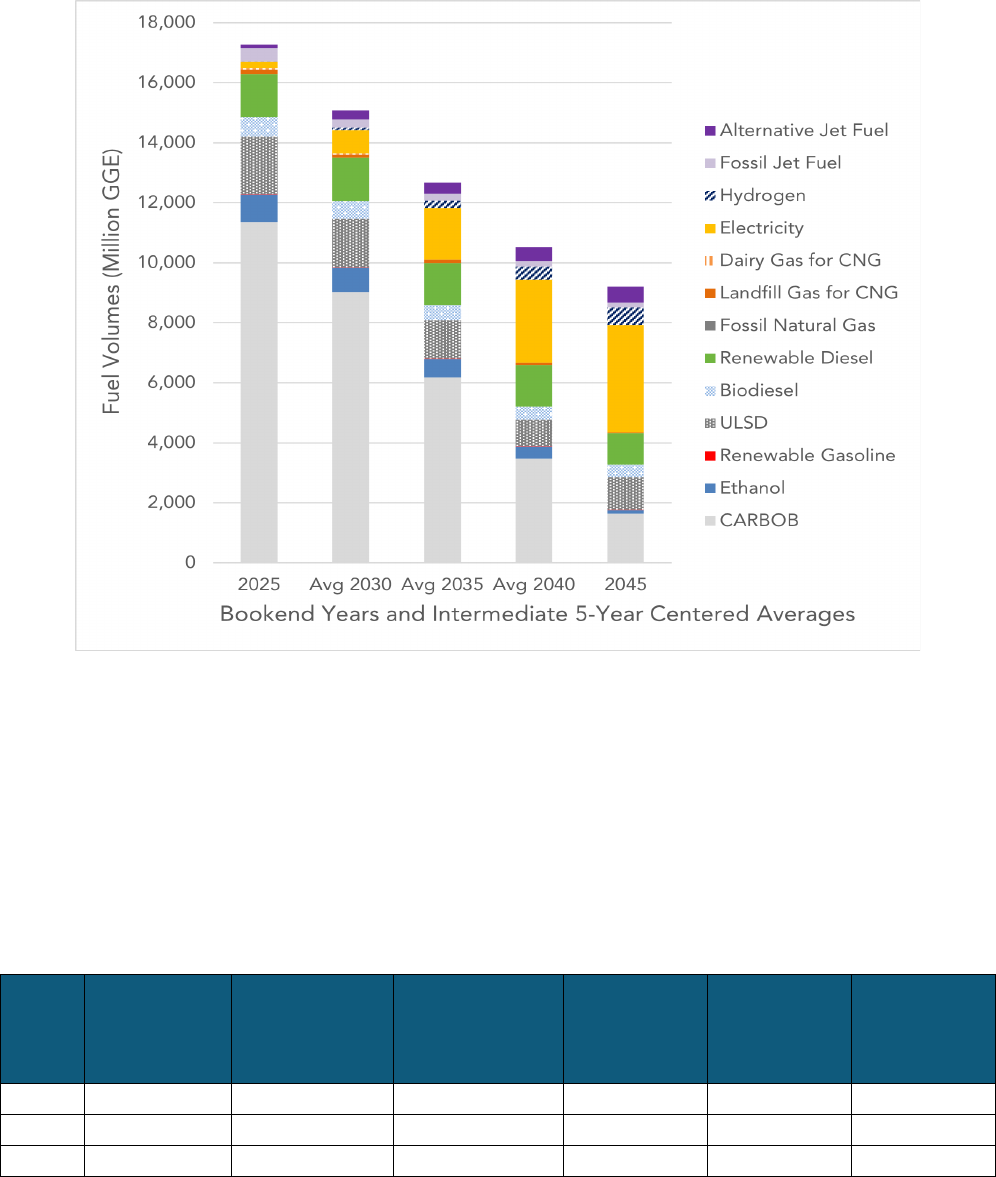

Meeting this demand requires building out significant new low-carbon energy supply capacity,

which the LCFS incentivizes in the transportation sector. Specifically, a greater demand for

electricity and renewable hydrogen is expected, necessitating the expansion of renewable

electricity and hydrogen production; the transition of low-carbon liquid biofuels from end-uses

from on-road vehicles with many zero-emission options into sectors that are more difficult to

decarbonize like aviation, marine, and other off-road uses; and transition of biomethane used

as compressed natural gas (CNG) in vehicles to a feedstock for hydrogen or an energy source

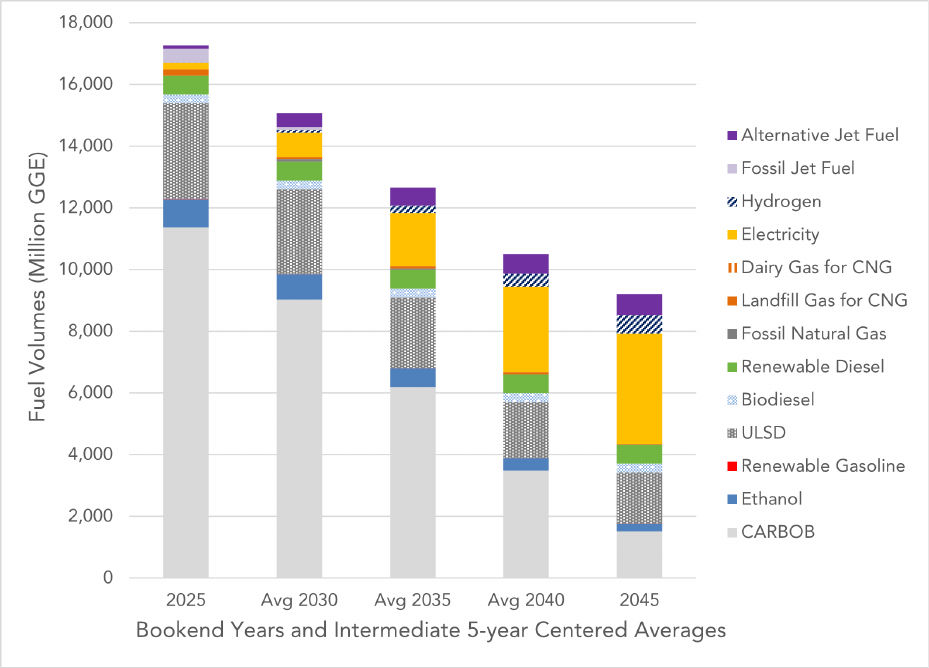

to decarbonize the broader natural gas system. Successful implementation of the technology

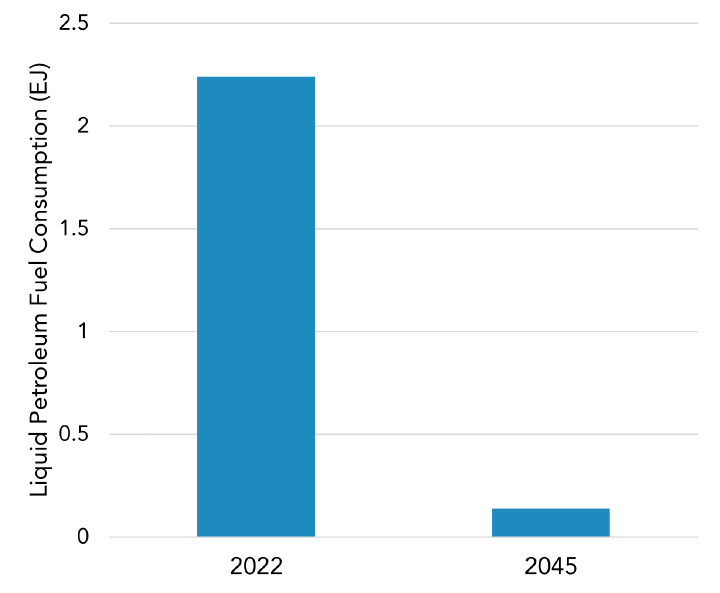

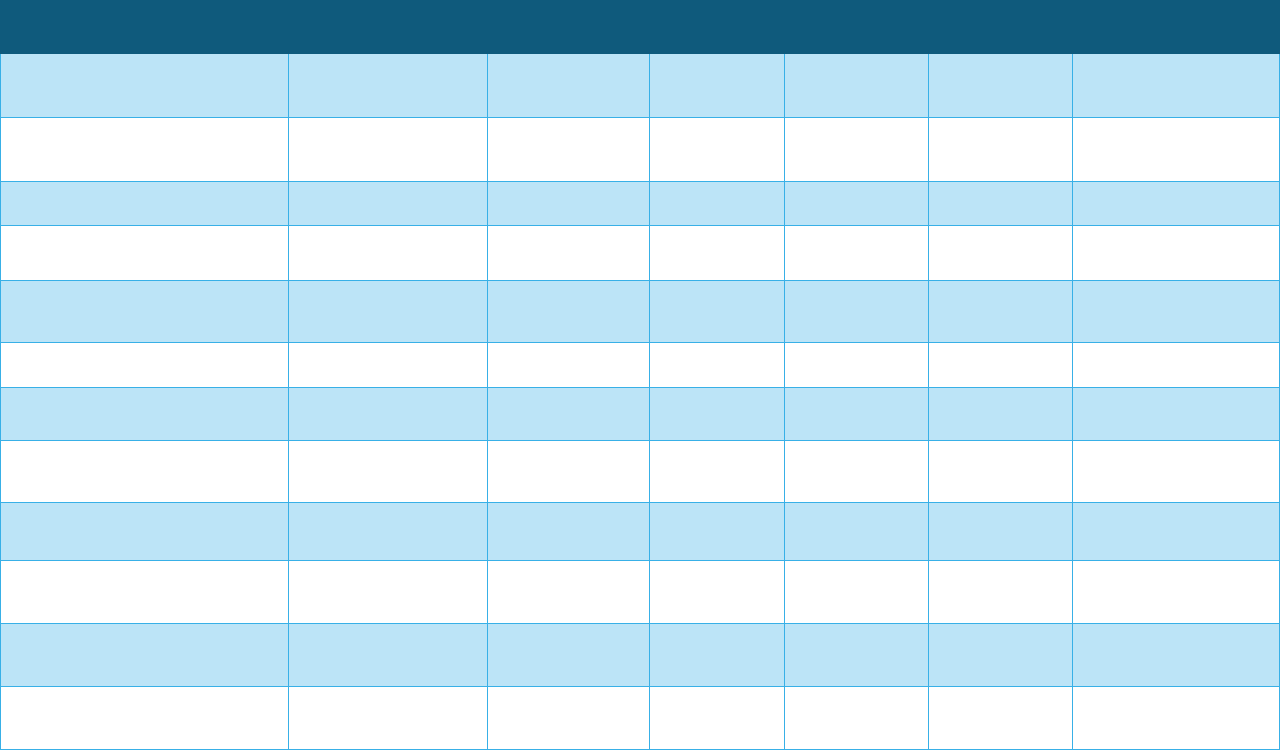

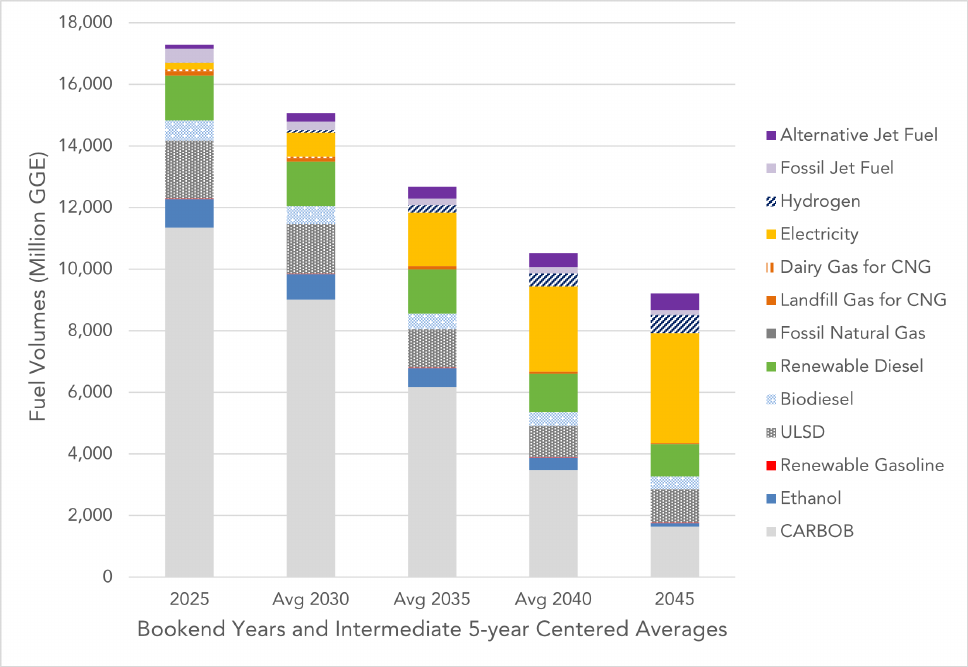

and fuel switching called for in the 2022 Scoping Plan Update results in a 94% reduction in

liquid petroleum demand by 2045 compared to 2022, as shown in Figure 1. For these

outcomes to happen, California must accelerate the pace of clean energy and technology

deployment. Private investments, policy signals such as a more stringent LCFS, and federal

incentives will all need to be leveraged to realize the outcomes in the 2022 Scoping Plan

Update.

3

State of California Executive Department, Executive Order N-79-20. September 23, 2020.

https://www.gov.ca.gov/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/9.23.20-EO-N-79-20-Climate.pdf

8

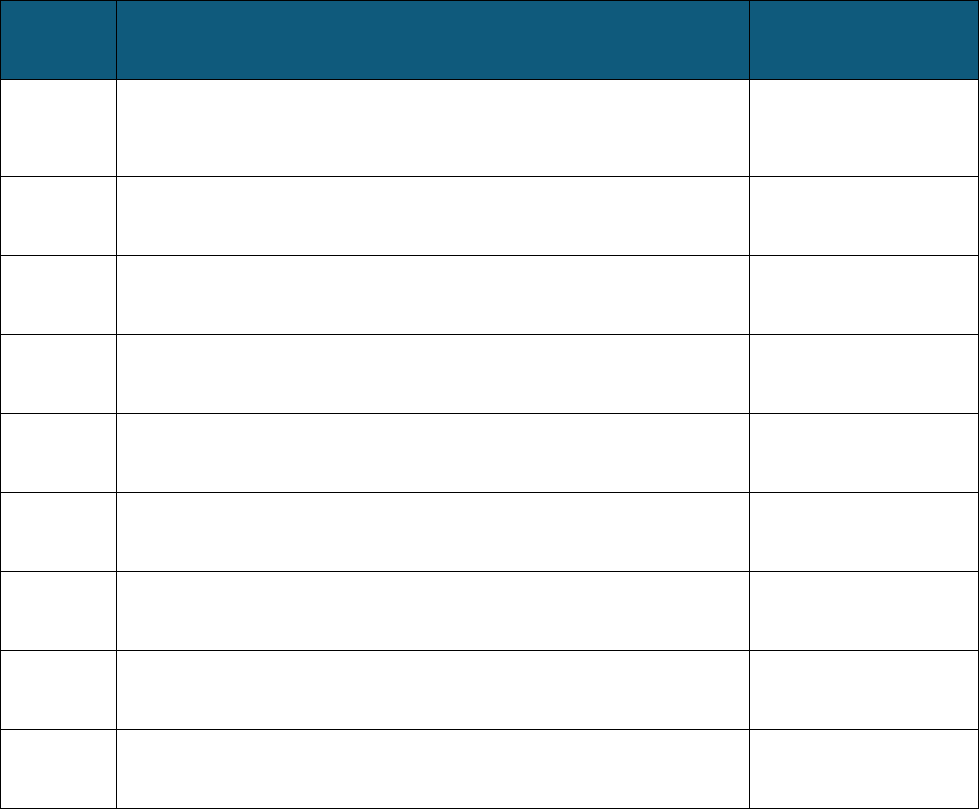

Figure 1: Fossil Fuel Demand Projections in 2045 relative to 2022 (from 2022 Scoping Plan Update)

The LCFS also supports other existing State GHG reduction efforts; notably, the Short-Lived

Climate Pollutant (SLCP) Reduction Strategy, Advanced Clean Cars II (ACC II) regulations,

Advanced Clean Fleets (ACF) regulation, Clean Truck Partnership, Advanced Clean Trucks

(ACT) regulation, 2020 Mobile Source Strategy, Sustainable Freight Action Plan (SFAP),

Commercial Harbor Craft (CHC) regulation, In-Use Locomotive regulation, Innovative Clean

Transit (ICT) regulation, and Renewable Portfolio Standard (RPS). SB 1383 (Lara, Chapter

395, Statutes of 2016) requires a 40% reduction in California’s methane emissions by 2030

and the LCFS facilitates significant private investment in technologies that provide the

methane reductions from dairy, livestock manure, organic waste, and landfill management

operations called for by SB 1383. On the vehicle side, ACC II serves as the primary

mechanism to help deploy ZEVs in the light-duty vehicle (LDV) sector. The LCFS supports

ACC II implementation by incentivizing electricity and hydrogen infrastructure through the ZEV

infrastructure crediting provisions, providing credits for the delivery of low-CI electricity and

hydrogen to vehicles, and through rebate and other transportation electrification support from

the proceeds from LCFS credit sales earned by electric utilities. Similarly, the opportunity to

generate LCFS credits helps to reduce the up-front costs for fleets to purchase new

zero-emission trucks, locomotives, and buses and equipment to achieve the SFAP, ACF, ICT,

In-Use Locomotive, and ACT goals. By recognizing the carbon intensity of renewable

electricity used to produce transportation fuels, the LCFS rewards fuel providers across the

supply chain for the displacement of fossil fuel consumption by biomethane, wind, solar, and

other lower carbon technologies, as well as the use of renewable power for vehicle charging.

Several of these regulations also require the use of renewable fuels during the transition to

zero-emission technology. The ICT regulation requires large transit agencies to use renewable

fuel in remaining combustion-powered buses, and the ICT and In-Use Locomotive regulations

9

support the use of hydrogen as well. The ACF regulation requires fleet turnovers beginning in

2024; however, this transition is contingent upon the availability of refueling infrastructure,

which this LCFS proposal would incentivize.

The LCFS provides the necessary price signals and incentives to leverage private investment

and scale the low-carbon fuel production needed to displace fossil fuels. This is borne out in

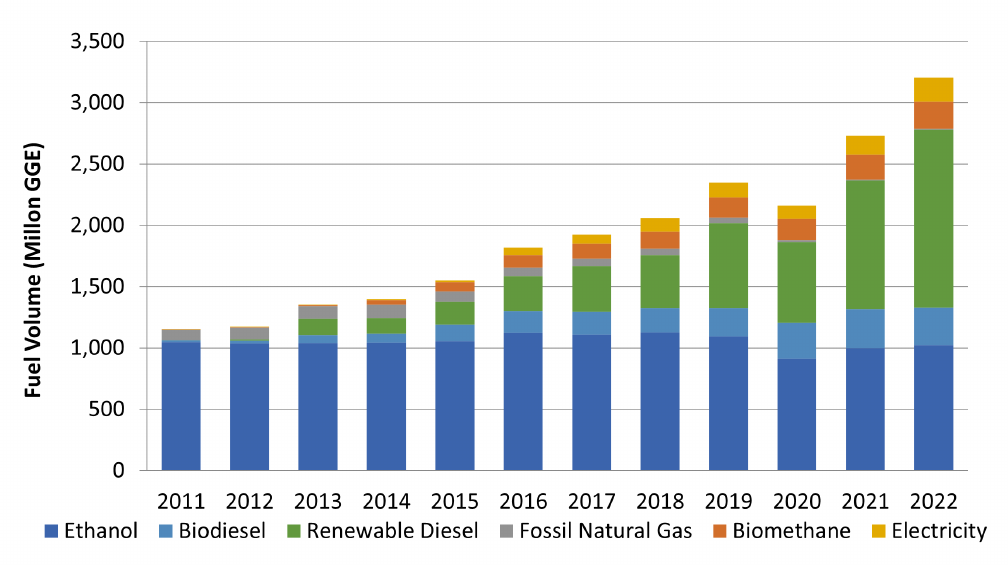

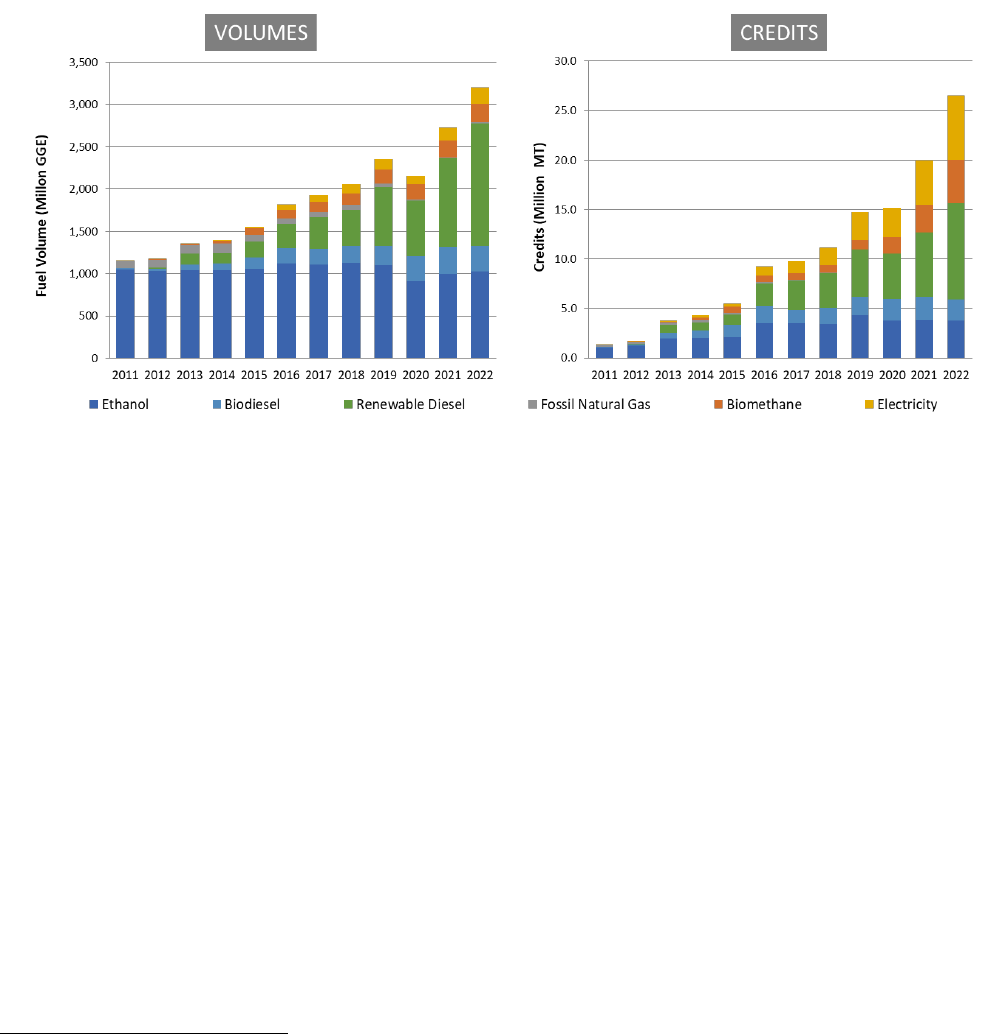

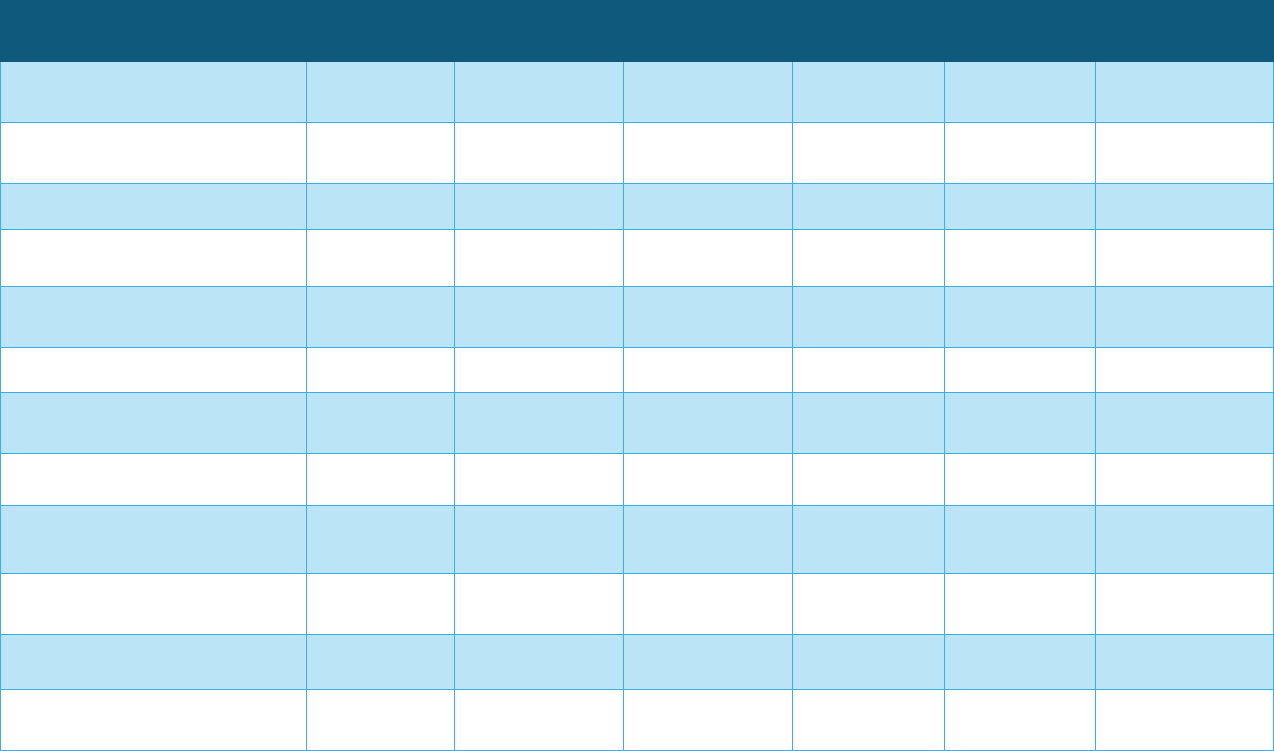

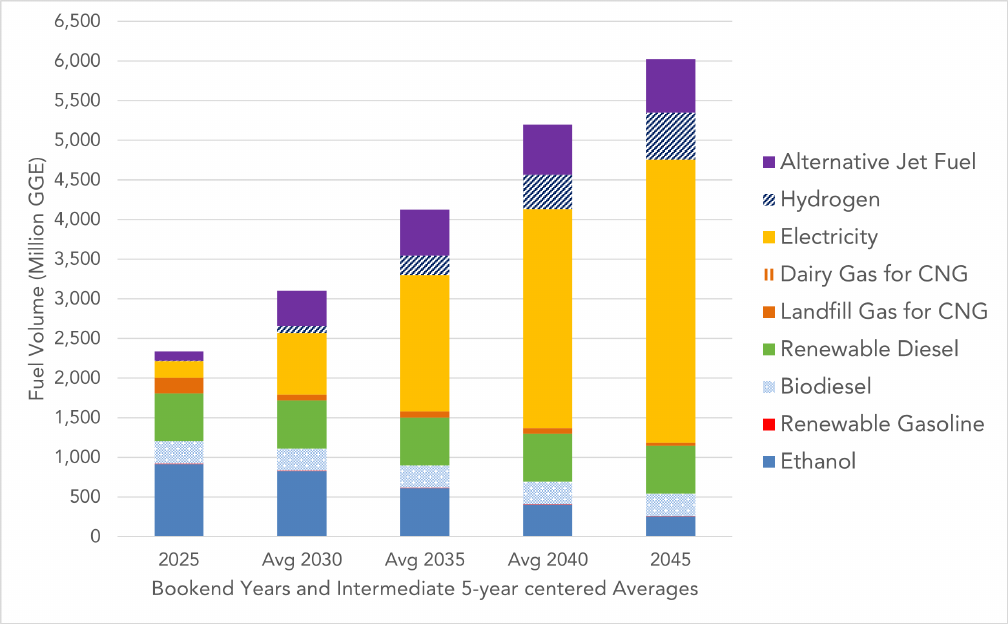

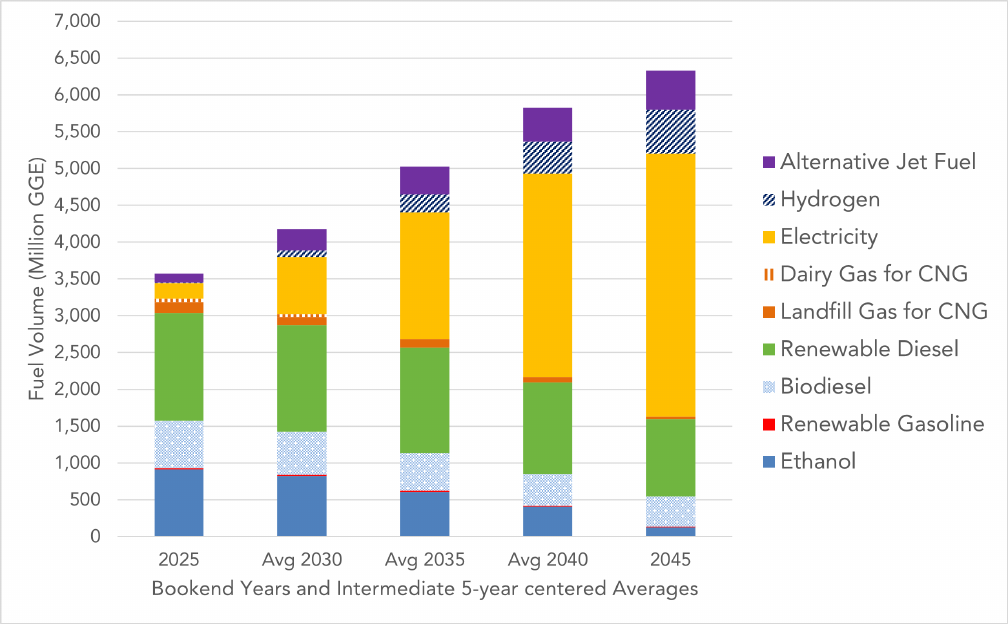

the program’s history. As shown in Figure 2, California has doubled the volume of the State’s

low-carbon fuel consumption in just 10 years and diversified the fuel mix considerably, due in

large part to the LCFS program.

Figure 2: Alternative Fuel Volumes in California between 2011-2022

The 2022 Scoping Plan Update directly identifies that the stringency of the LCFS CI

benchmarks should be increased, both pre- and post-2030, which is the key change staff is

proposing for this rulemaking. The objective is to send clear, long-term market signals to

support investment in low-carbon fuel production and technologies that are needed to achieve

deep emissions reductions in the transportation sector while supporting the broader portfolio of

zero-emission vehicle regulations and climate statutes. Another goal is to align the crediting

opportunities in the LCFS with the fuel and technology pathways identified in the 2022 Scoping

Plan Update. To encourage additional GHG reductions in key areas where decarbonization will

be important to meet long-term climate goals, staff proposes to eliminate the current exemption

for intrastate fossil jet fuel starting in 2028 and expand ZEV infrastructure crediting to the

medium- and heavy-duty vehicle sector under the program. Given the need to quickly scale

low-carbon fuel production in this decade and staff’s experience implementing the program for

over a decade, staff also proposes to update and streamline several quantification methods

and analysis tools so that the program does not unnecessarily slow down the investment or

availability of low-carbon fuels and so other jurisdictions can establish similar programs without

significant administrative needs. As a means of increasing the flexibility of the program to be

10

able to respond to rapid and unanticipated shifts in the market, such as significant

overperformance of ACC II or ACF implementation, staff also proposes a mechanism that

would automatically accelerate the carbon intensity benchmarks under certain conditions.

Finally, in response to the near-term over-performance, staff has included a step down in the

carbon intensity beginning in 2025.

A. Overview of the Low Carbon Fuel Standard

Transportation plays a key role in California’s economy and lifestyle. The production and use

of traditional petroleum-derived transportation fuels—such as gasoline and diesel—are

responsible for almost 50% of statewide GHG emissions, the largest source of GHG emissions

in 2020.

4

The LCFS is part of the State’s set of policies to meet California’s ambitious climate

goals, which are described in the 2022 Scoping Plan Update. The 2022 Scoping Plan Update

demonstrates that significant increases in low-carbon fuel and technologies are needed in a

faster timeframe than we have historically seen.

The LCFS is designed to decrease the carbon intensity of California’s transportation fuel pool

and provide an increasing range of low-carbon and renewable alternatives, which reduce

petroleum dependency and achieve air quality benefits.

5

Providers of transportation fuels must cumulatively demonstrate that the mix of fuels they

supply for use in California meets the LCFS carbon intensity standards, or benchmarks, for

each annual compliance period. Regulated entities required to report fuels provided may

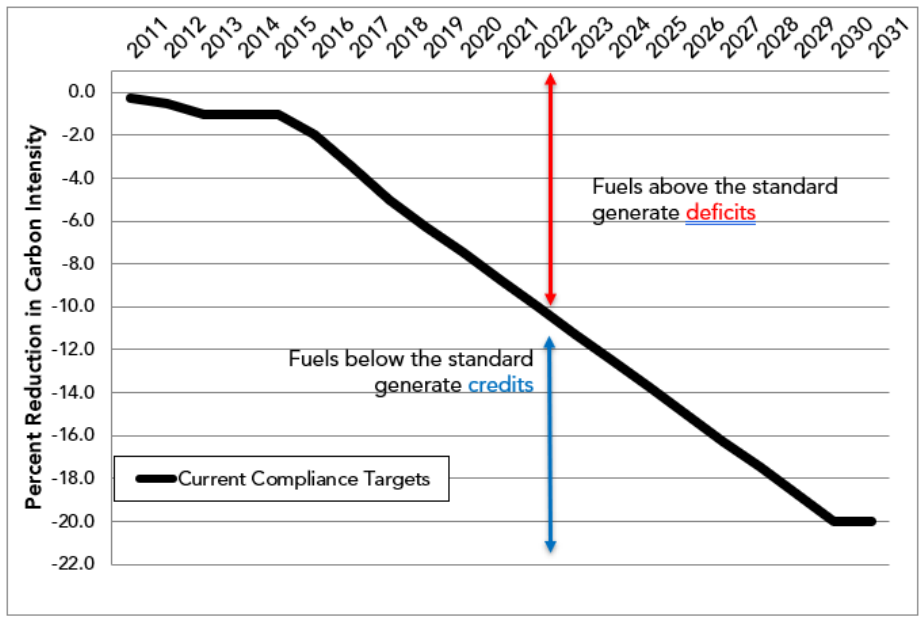

demonstrate compliance through a system of credits and deficits. Credits are generated by

supplying fuels with lower carbon intensity than the benchmark. Deficits result from supplying

fuels with higher carbon intensity than the benchmark. This concept is illustrated in Figure 3. A

deficit generator meets its compliance obligation by retiring credits it earns or otherwise

acquires from another party equal to the deficits it has incurred. Credits and deficits are

generally determined based on the quantity of fuel sold, the carbon intensity of the fuel, and

the efficiency by which a vehicle converts the fuel into usable energy.

4

California Air Resources Board, California Greenhouse Gas Emissions for 2000 to 2020, Trends of Emissions

and Other Indicators. Pages 10-14. 2022. https://ww2.arb.ca.gov/sites/default/files/classic/cc/inventory/2000-

2020_ghg_inventory_trends.pdf. This includes upstream oil extraction and refining emissions.

5

Carbon Intensity (CI) is a measure of the GHG emissions associated with the various production, distribution,

and consumption steps in the “life cycle” of a transportation fuel, denoted in units of gCO

2

e/MJ.

11

Figure 3: Illustration of LCFS Mechanics – How Credits and Deficits are Calculated

There are three ways to generate credits in the LCFS: fuel pathways, projects, and

capacity-based crediting. Under fuel pathway-based crediting, all transportation fuels need a

CARB-certified carbon intensity score to participate in the LCFS, and the fuel type dictates

which process is used to determine that CI. Additionally, there are CARB-approved LCFS

project-based actions that may generate credits, such as by demonstrating carbon capture and

sequestration, using solar-generated steam at oil and gas extraction sites, and investing in

refinery improvements that reduce GHG emissions. Finally, the 2018 amendments added

capacity-based crediting to support the deployment of ZEV refueling infrastructure. Crediting

for ZEV infrastructure is based on the capacity of the hydrogen station or fast charging site

minus the actual fuel dispensed. Credits and deficits are denoted in metric tons of GHG

emissions. Credits may be banked and traded within the LCFS market to meet compliance

obligations.

The LCFS carbon intensity benchmarks are an annually declining standard, which is defined in

the LCFS regulation as a percentage reduction from the historical average carbon intensity of

gasoline and diesel fuel in the year 2010. To determine the carbon intensity value of a

particular fuel, the GHG emissions from the fuel’s life cycle are summed and divided by the

fuel’s energy content (in megajoules). GHG emissions from each step can include carbon

dioxide (CO

2

), methane (CH

4

) and nitrous oxide (N

2

O), which are adjusted by the

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change global warming potentials to their CO

2

equivalent.

Thus, carbon intensity is expressed in terms of grams of CO

2

equivalent per megajoule

(gCO

2

e/MJ).

12

The LCFS is based on the principle that each fuel has life cycle GHG emissions. This life cycle

assessment (LCA) examines the GHG emissions associated with the production,

transportation, and use of a given fuel. The LCA includes direct emissions from the energy and

material inputs for the production, transport, and use of the fuels, as well as significant GHG

emissions from market-driven changes, such as changes in land use for some crop-derived

biofuels, and emissions that may result from market displacement effects (e.g., when a

material is diverted from its historic use in order to produce a fuel, causing increased demand

for another material to substitute the fuel for feedstock). The system of declining benchmarks

that is used to calculate credits and deficits, and the obligation of deficit-generating fuels to be

canceled out by credits, result in a decrease in the total life cycle GHG emissions from the

transportation fuel pool in California.

A more complete description of how the LCFS regulation is designed to work, as well as its

underlying scientific and economic principles, can be found in the initial and final statements of

reasons for the original 2009 rulemaking,

6

and the 2011,

7

2015,

8

2018,

9

and 2019 LCFS

rulemakings.

10

6

California Air Resources Board, Proposed Regulation to Implement the Low Carbon Fuel Standard Volume I

Staff Report: Initial Statement of Reasons. March 5, 2009.

https://ww2.arb.ca.gov/sites/default/files/barcu/regact/2009/lcfs09/lcfsisor1.pdf

California Air Resources Board, Proposed Regulation to Implement the Low Carbon Fuel Standard Volume II

Appendices, March 5, 2009.

https://ww2.arb.ca.gov/sites/default/files/barcu/regact/2009/lcfs09/lcfsisor2.pdf

California Air Resources Board, Final Statement of Reasons for Rulemaking. December 2009.

https://ww2.arb.ca.gov/sites/default/files/barcu/regact/2009/lcfs09/lcfsfsor.pdf

7

California Air Resources Board, Staff Report: Initial Statement of Reasons for Rulemaking: Proposed

Amendments to the Low Carbon Fuel Standard. October 26, 2011.

https://ww2.arb.ca.gov/sites/default/files/barcu/regact/2011/lcfs2011/lcfsisor.pdf

California Air Resources Board, Final Statement of Reasons: Amendments to the Low Carbon Fuel Standard

Regulation. October 2012. https://ww2.arb.ca.gov/sites/default/files/barcu/regact/2011/lcfs2011/lcfsfsor.pdf

8

California Air Resources Board, Staff Report: Initial Statement of Reasons for Rulemaking. Proposed Re-

Adoption of the Low Carbon Fuel Standard Regulation. December 31, 2014.

https://ww2.arb.ca.gov/sites/default/files/barcu/regact/2015/lcfs2015/lcfs15isor.pdf

California Air Resources Board, Final Statement of Reasons for Rulemaking, Including Summary of Comments

and Agency Response: Re-adoption of the Low Carbon Fuel Standard Regulation. 2015.

https://ww2.arb.ca.gov/sites/default/files/barcu/regact/2015/lcfs2015/fsorlcfs.pdf

9

California Air Resources Board, Public Hearing to Consider Proposed Amendments to the Low Carbon fuel

Standard Regulation and to the Regulation on Commercialization of Alternative Diesel Fuels. Staff Report: Initial

Statement of Reasons. March 6, 2018.

https://ww2.arb.ca.gov/sites/default/files/barcu/regact/2018/lcfs18/isor.pdf?_ga=2.233093594.551189306.169264

1515-1059366641.1629756188

California Air Resources Board, Addendum to the Final Statement of Reasons for Rulemaking: Amendments to

the Low Carbon Fuel Standard Regulation and to the Regulation on Commercialization of Alternative Diesel

Fuels. Final Statement of Reasons. January 3, 2019.

https://ww2.arb.ca.gov/sites/default/files/barcu/regact/2018/lcfs18/lcfsaddendum.pdf?_ga=2.112540034.74953622

0.1693580753-1565224836.1601474474

10

California Air Resources Board, Public Hearing to Consider Proposed Amendments to the Low Carbon Fuel

Standard Regulation and to the Regulation on Commercialization of Alternative Diesel Fuels. Staff Report: Initial

Statement of Reasons. October 1, 2019.

https://ww2.arb.ca.gov/sites/default/files/barcu/regact/2019/lcfs2019/isor.pdf

California Air Resources Board, Amendments to the Low Carbon Fuel Standard Regulation, Final Statement of

Reasons. April 2020. https://ww2.arb.ca.gov/sites/default/files/barcu/regact/2019/lcfs2019/fsor.pdf

13

B. History and Current Status of the Low Carbon Fuel Standard

CARB initially approved the LCFS regulation in 2009 as an early action measure under AB 32

and began implementation in 2010. Throughout the 14 years since the Board’s original

adoption, the basic framework of the current LCFS—including the use of LCA, the LCFS credit

market, and the electronic registry of fuel reporting—has worked well and continues to support

growth in an increasingly diverse and low-carbon transportation fuel pool.

CARB approved revisions to the LCFS in December 2011, which became effective on

November 26, 2012, and were implemented by CARB on January 1, 2013. On July 15, 2013,

the State of California Court of Appeal, Fifth Appellate District (Court) issued its opinion in

POET, LLC versus California Air Resources Board (2013) 218 Cal.App.4

th

681, resulting in a

stay of the LCFS. The Court held that the LCFS adopted in 2009 and implemented in 2010

(referred to as 2010 LCFS) would remain in effect and that CARB could continue to implement

and enforce the 2013 regulatory standards while taking steps to remedy California

Environmental Quality Act and Administrative Procedure Act issues as required in the ruling.

To address the court ruling, CARB brought a revised LCFS regulation to the Board for

readoption in February 2015. The 2015 rulemaking included many amendments, updates, and

improvements to the program, including a compliance schedule that maintained the 2009

LCFS regulation’s target of a 10% reduction in average carbon intensity by 2020 from a 2010

baseline. On September 24, 2015, the Board approved that revised LCFS regulation, which

became effective on January 1, 2016.

In September 2018, the Board approved amendments to the LCFS regulation, which became

effective on January 4, 2019. The 2018 rulemaking included many amendments, updates, and

improvements to the program, including strengthening the CI reduction benchmarks to a 20%

reduction from a 2010 baseline by 2030, in line with the 2017 Scoping Plan Update and

California’s 2030 GHG target enacted through SB 32 (Pavley, Chapter 249, Statutes of 2016)

and adding a third-party verification provision to enhance the integrity of the program.

As part of the hearings to adopt the amendments proposed in 2018, the Board directed the

Executive Officer to monitor the cost containment provisions of the LCFS program, including

the Credit Clearance Market, and to propose technical adjustments through future rulemaking

to strengthen the cost containment provisions, if needed. The Board also directed the

Executive Officer to work with stakeholders to establish an equity-based framework for the

possible uses of base credit value from residential charging, consistent with legislative

priorities. To address Board direction, CARB brought changes focusing on strengthening the

cost containment provisions of the LCFS program and addressing equity in the use of LCFS

credit value for electricity to the Board through a rulemaking in 2019. In April 2020, the Board

approved the current LCFS regulation. The current regulation became effective on July 1,

2020.

California is receiving significant volumes of low-carbon fuels in response to the LCFS,

including ethanol, biomass-based diesel, biomethane, and low-CI electricity. In addition to

increased volumes, fuel producers have also been successfully reducing the carbon intensity

of their fuels over the past years by using low-carbon feedstocks, improving production

efficiency, and reducing fugitive emissions. The effect of both increasing volumes of

low-carbon fuels and reduced carbon intensity of those fuels has meant that California’s overall

petroleum fuel use has declined by 1.3 billion gallons since 2019, the overall carbon intensity

14

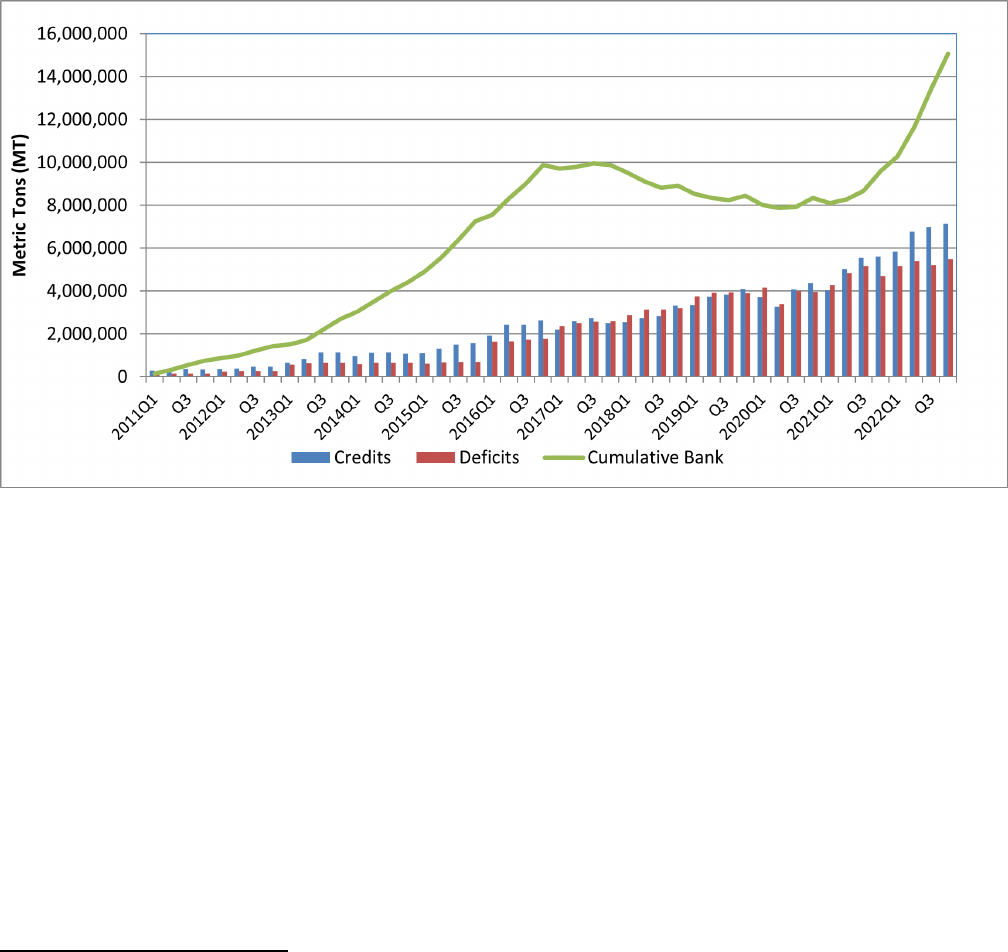

of California’s transportation fuels has declined by 12.63% relative to 2010 levels, and the

LCFS credit bank of excess credits has grown to its highest level to date with 15 million credits,

as shown in Figure 7. The financial benefits are distributed among providers of various

alternative fuels (as illustrated in Figure 3), geographically across California,

11

and across the

participating credit generators.

12

Figure 4: Quarterly Credits and Deficits for All Fuels Reported and Cumulative Credit Bank (Q1 2011 through Q4

2022)

By decarbonizing the transportation fuel sector, the LCFS has resulted in increased

diversification of transportation fuel options in California and less dependence on fossil fuels.

Before the LCFS, the only alternative fuels with market share were natural gas and ethanol.

Since the inception of the LCFS, California has doubled the volume of low-carbon fuel

consumption and diversified the fuel mix considerably. Collectively, alternative fuels supported

by the LCFS displaced over 3.9 billion gallons of petroleum fuel in 2022 in California. More

recently, renewable diesel and electricity have taken on an increasingly larger share of the fuel

pool, as shown in Figure 8. Electric vehicle (EV) charging has increased substantially in the

last few years, and it is expected that electric vehicles will be an increasing portion of the

market share, driven in part by California’s vehicle regulations, including ACC II, ICT, and ACF

regulations in conjunction with recent federal incentives. Renewable diesel capacity also

increased by over 500% between 2013 and 2020, and many U.S. fuel producers have made

11

Beneficiaries include California municipal transit agencies, fueling facilities, equipment service providers,

utilities, as well as fuel producers and project developers across the United States and abroad.

12

California Air Resources Board, LCFS Data Dashboard Figure 9: LCFS Credit Market Net Position Histogram.

(Updated on July 31, 2023).

https://ww2.arb.ca.gov/resources/documents/lcfs-data-dashboard

15

announcements for expanded production in the coming years. Nearly half of California’s diesel

pool was composed of alternative fuels in 2022.

13

Figure 5: Annual Alternative Fuel Volumes and Credit Generation by Fuel Type

In addition to increases in renewable diesel and electricity, hydrogen and alternative jet fuel

(AJF) quantities reported to the LCFS have increased as well. Since 2019, when AJF became

eligible as an opt-in fuel in the LCFS, volumes have increased from about 1.8 million gallons in

2019 to about 11.6 million gallons in 2022, and those volumes continue to increase as

momentum builds in the aviation sector and with new federal incentives. Hydrogen quantities,

although still relatively small, nearly doubled from 2018 to 2019, and have more than

quadrupled since 2018.

14

The program is also supporting refueling infrastructure needed to

refuel ZEVs. The 2018 LCFS amendments added the Hydrogen Refueling Infrastructure (HRI)

and Direct Current (DC) Fast Charging Infrastructure (FCI) provisions. These provisions are

designed to support the buildout of publicly-available ZEV refueling infrastructure for light-duty

vehicles in California in the early years while refueling demand is low, with the expectation that

vehicle demand will increase as refueling availability increases. Crediting is provided for

eligible infrastructure based on the unused refueling capacity, and credit generation phases

out naturally as fueling throughput increases and unused capacity decreases. The provisions

limited infrastructure crediting to 5% of deficits and required applications to be submitted prior

to 2026. To date, CARB has approved 75 hydrogen stations and over 3,200 DC fast chargers

at 511 sites.

15

Over 30 million LCFS credits were sold or traded in approximately 3,100 transactions in 2022,

demonstrating an active credit market with an annual transactional value of nearly $4 billion.

13

California Air Resources Board, LCFS Quarterly Data Spreadsheet. (Updated on July 31, 2023).

https://ww2.arb.ca.gov/resources/documents/lcfs-data-dashboard

14

Ibid.

15

California Air Resources Board, LCFS ZEV Infrastructure Crediting webpage. (Accessed on April 18, 2023).

https://ww2.arb.ca.gov/resources/documents/lcfs-zev-infrastructure-crediting

16

Credits in 2022 were generated primarily from renewable diesel (36%), electricity (24%),

biomethane (16%), and ethanol (14%). More than 522 active entities are registered for

reporting in the LCFS Reporting Tool and Credit Bank & Transfer System (LRT-CBTS), and

more than 1,300 individual alternative fuel pathways have been approved with carbon

intensities below the current benchmarks.

The current LCFS targets a 20% reduction in fuel carbon intensity by 2030 and maintains that

benchmark for all subsequent years. A primary objective of this rulemaking is to strengthen the

carbon intensity benchmarks of the LCFS regulation both pre- and post-2030 so that the LCFS

continues to serve as a key policy to reduce GHG emissions from the transportation sector.

Achieving the GHG reduction goals of the 2022 Scoping Plan Update will require significant

changes in every sector of the State’s economy. California’s transportation industry remains

the largest contributing sector to the GHG Inventory,

16

and transitioning to ZEVs and deploying

low-carbon fuels is critical for achieving California’s climate and air quality targets.

Federal policy support plays a role in the fuels and technologies that come to California

through the LCFS. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (U.S. EPA) implements a

Renewable Fuel Standard (RFS) program (Code of Federal Regulations, title 40, part 80,

sections 1100 et. Seq.) that mandates the blending of specific volumes of renewable fuels into

gasoline and diesel sold in the U.S. to achieve a specified ratio for each year. As defined,

“renewable fuels” under the RFS resemble the list of transportation fuels subject to the LCFS.

The two policies are complementary and support a reduction in fossil fuel consumption and

diversification of the fuel pool. In addition to the RFS, the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) of

2022

17

provides tax incentives and financial support for biofuel and hydrogen production. The

newly created Hydrogen Production Tax Credit (45V)

18

incentivizes the domestic production of

clean hydrogen, which will make this emerging low-carbon fuel source more cost-competitive

and help the country meet the ambitious goals of the Hydrogen Shot

19

, an effort to accelerate

breakthroughs in hydrogen technology and cut the cost of clean hydrogen by 80% to $1 per

kilogram in one decade. This federal support represents a once-in-a-generation investment in

clean fuel production and infrastructure, and California is poised to leverage the existing LCFS

mechanism to bring investment to California. The LCFS also supports use of carbon capture

and sequestration (CCS) in connection with transportation fuel production, and direct air

capture (DAC) with carbon sequestration projects. These capital-intensive projects are also

supported by the federal government through the 45Q tax credit for CCS

20,21

and research and

16

California Air Resources Board, Current California GHG Emission Inventory Data (2022 Edition).

https://ww2.arb.ca.gov/ghg-inventory-data

17

117

th

Congress, Inflation Reduction Act of 2022. Pub.L. No. 117-169. August 16, 2022.

https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/house-bill/5376/text

18

The White House, Building a Clean Energy Economy: A Guidebook to the Inflation Reduction Act’s Investments

in Clean Energy and Climate Action. 74-76. January 2023. https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-

content/uploads/2022/12/Inflation-Reduction-Act-Guidebook.pdf

19

United States Department of Energy Office of Energy Efficiency & Renewable Energy, Hydrogen Shot:

Overview. (Accessed on December 13, 2023). https://www.energy.gov/eere/fuelcells/hydrogen-shot

20

Congressional Research Service, Carbon Storage Requirements in the 45Q Tax Credit. IF11639. June 28,

2021. https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IF/IF11639

21

The Inflation Reduction Act of August 2022 expands and enhances the 45Q credit for CCS. Pub.L. No. 117-169

(August 16, 2022).

17

deployment grants from federal agencies.

22,23

Investments in California leveraging federal

support will be key to achieving the deep emissions reductions called for in AB 1279 and the

2022 Scoping Plan Update.

Like so many of CARB’s innovative programs, the success of California’s LCFS program is

inspiring other jurisdictions to adopt their own clean fuels programs. CARB works closely with

other jurisdictions that have chosen to adopt similar programs, including Oregon, Washington,

and British Columbia. CARB also collaborates closely with other states and is seeing growing

interest from several jurisdictions. Other jurisdictions including Japan, New Zealand, Australia,

and the European Commission also continue to seek information and technical experience on

the LCFS. As interest in the LCFS grows and other jurisdictions consider their own programs,

CARB continues to improve efficiency and maintain program integrity to ensure that the LCFS

remains an exportable policy.

C. Overview of the Proposed Amendments

This section provides a broad overview of amendments staff is proposing for adoption. Chapter

II provides a more in-depth description of the purpose of the rulemaking and the problems that

the proposal is intended to address. Appendix E provides a summary, purpose, and rationale

for each proposed regulatory modification.

The most significant change in this proposal is to strengthen the CI reduction benchmarks both

pre- and post-2030 in support of California’s goal for achieving carbon neutrality by 2045 and

achieving an 85% reduction in GHG emissions by 2045, as called for by AB 1279 and the 2022

Scoping Plan Update. The 2022 Scoping Plan Update, which identifies the outcomes needed

to achieve carbon neutrality by 2045, was approved by the Board in December 2022. The

State must accelerate the pace of clean energy and technology development, and the LCFS is

one of the primary mechanisms for transforming California’s transportation fuel pool with

low-carbon alternatives. The benchmarks provide the basis for calculating credits for

low-carbon fuels and deficits for high carbon fuels.

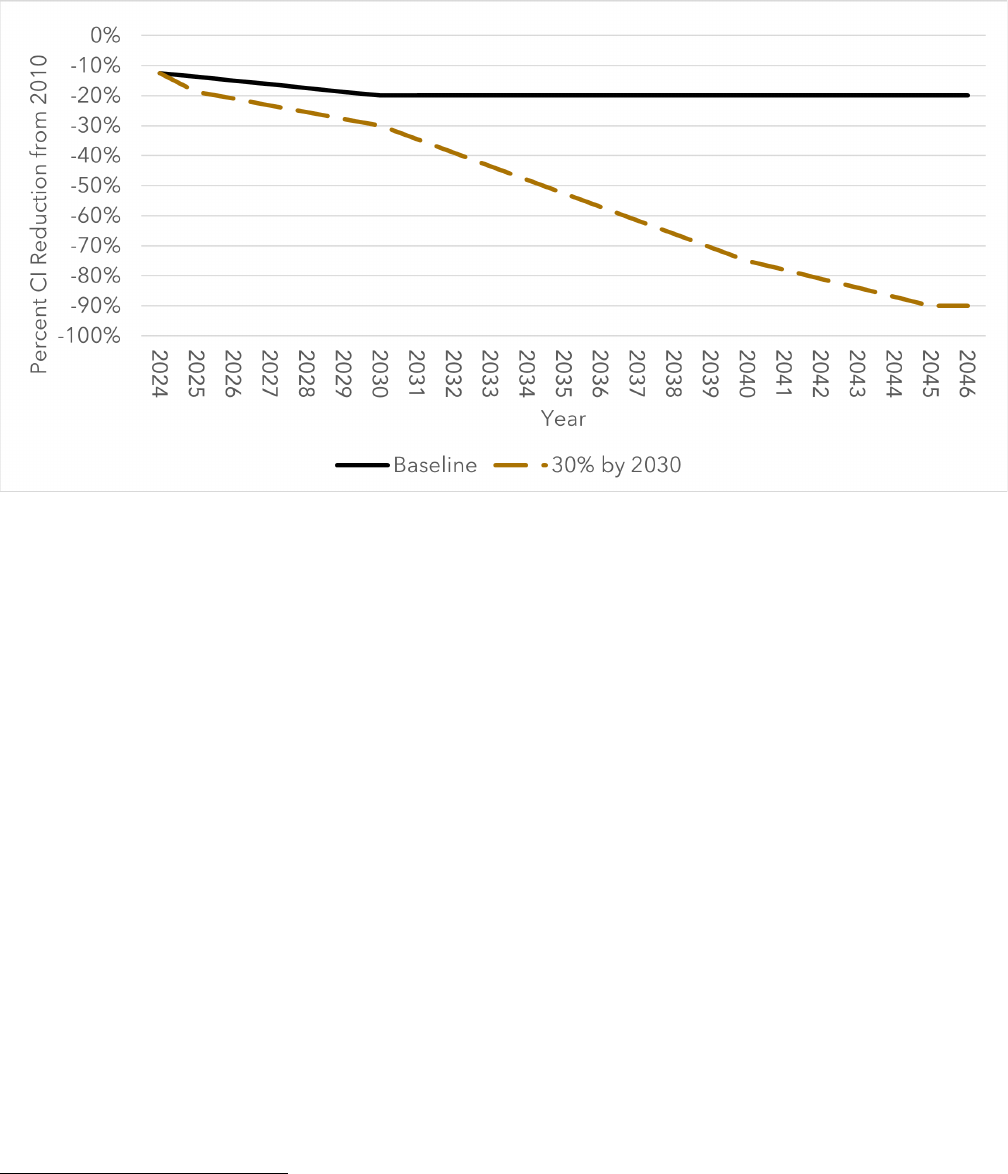

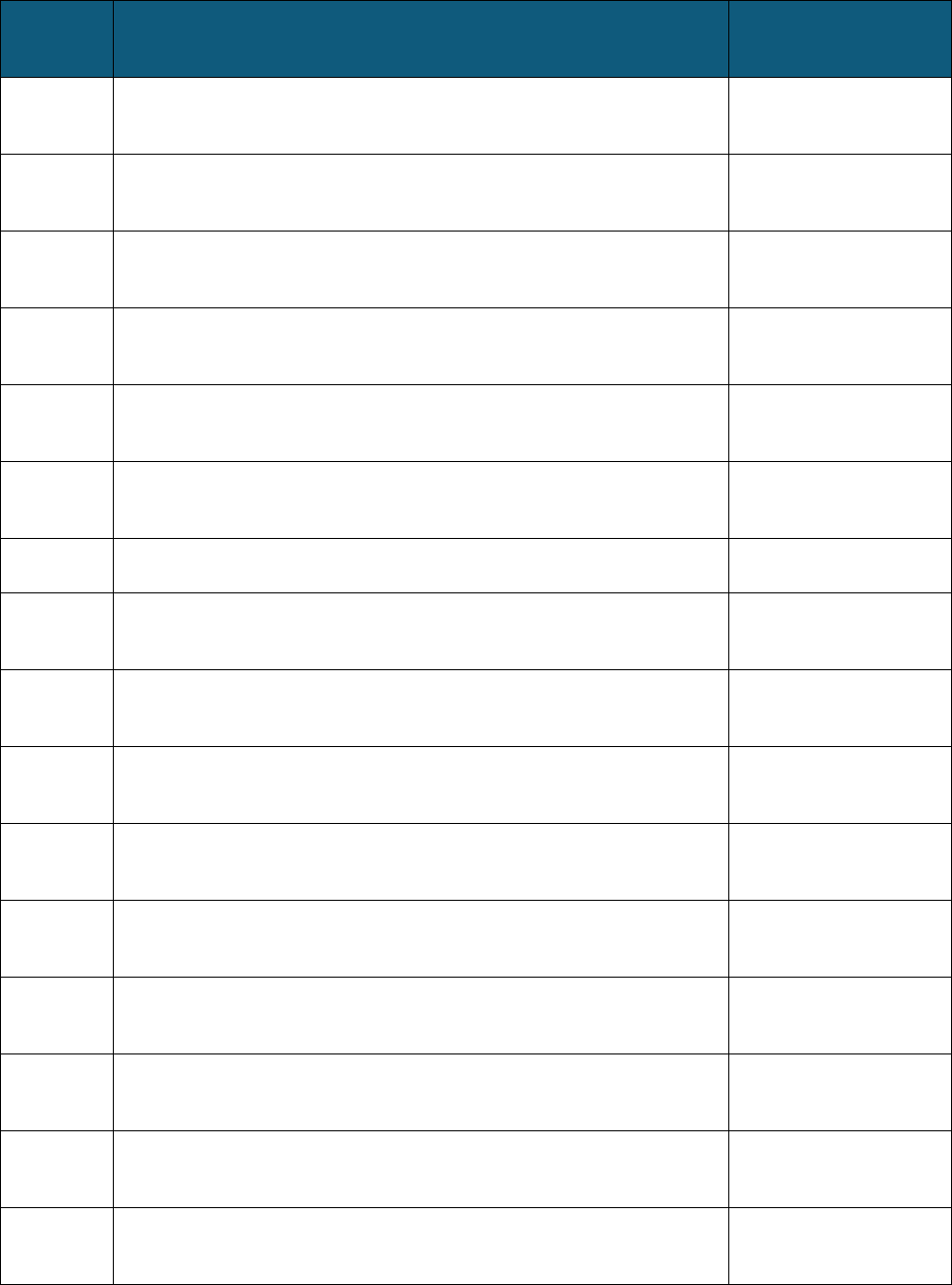

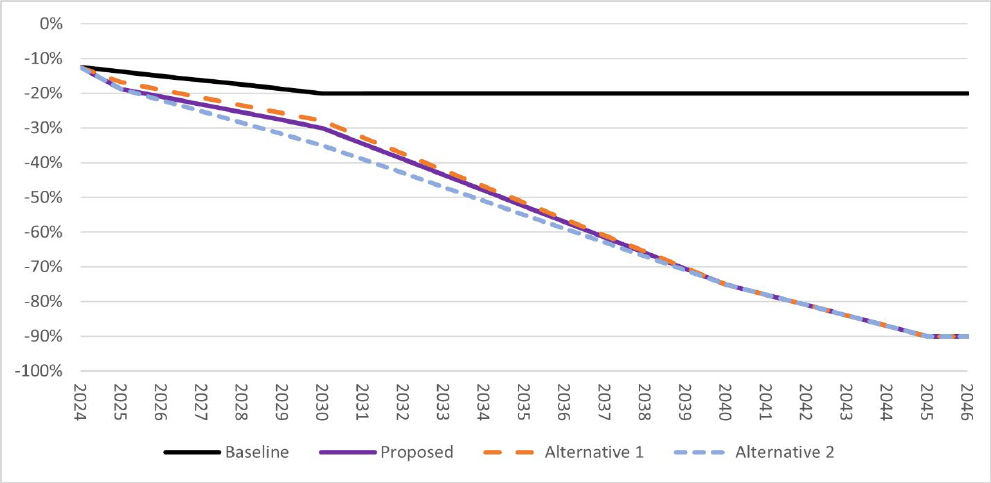

If adopted, the proposed amendments would require a 30% reduction in fuel CI by 2030 and a

90% reduction in fuel CI by 2045 from a 2010 baseline, as shown in the proposed CI

benchmark schedule for gasoline and gasoline substitutes listed in Table 1, below, and shown

in Figure 6. To accommodate rapid advances in transportation fuel production and use, the

proposed amendments also include a near-term step-down and an Automatic Acceleration

Mechanism (AAM). The step-down is a one-time 5% reduction in the CI benchmark in 2025

that increases the stringency of the CI target. The AAM is another tool to increase the

stringency of the CI benchmark, but is activated only when specific regulatory conditions are

22

United States Department of Energy, U.S. Department of Energy Announces $131 Million for CCUS

Technologies. April 24, 2020. https://www.energy.gov/articles/us-department-energy-announces-131-million-ccus-

technologies

23

United States Department of Energy, Funding Opportunity Announcement 2515, Carbon Capture R&D for

Natural Gas and Industrial Point Sources, and Front-End Engineering Design Studies for Carbon Capture

Systems at Industrial Facilities and Natural Gas Plants. October 6, 2021.

https://www.energy.gov/fecm/articles/funding-opportunity-announcement-2515-carbon-capture-rd-natural-gas-

and-industrial

18

met. These triggered reductions in the CI benchmark would help bolster market stability in the

event that transportation fuel decarbonization is growing rapidly and outpacing deficit

generation in the program.

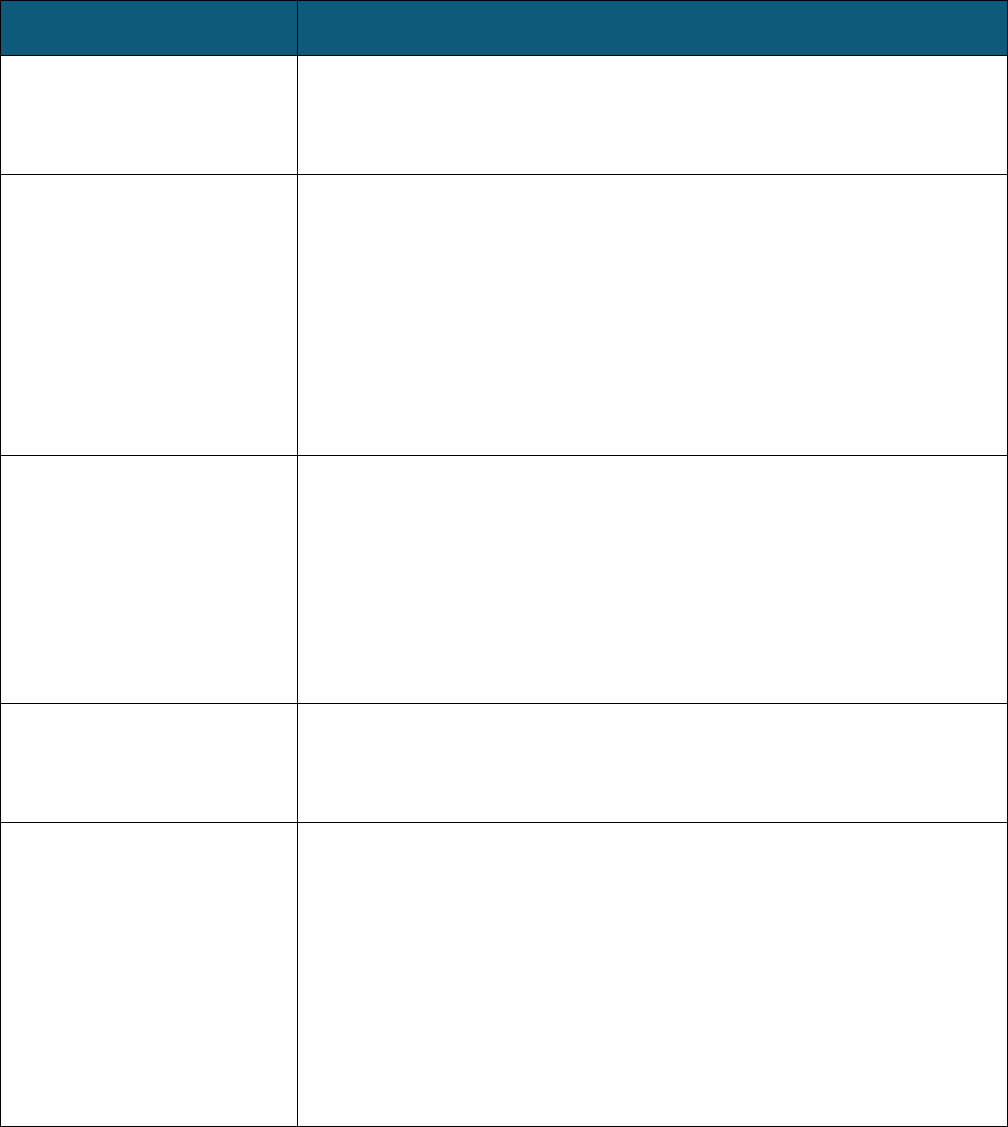

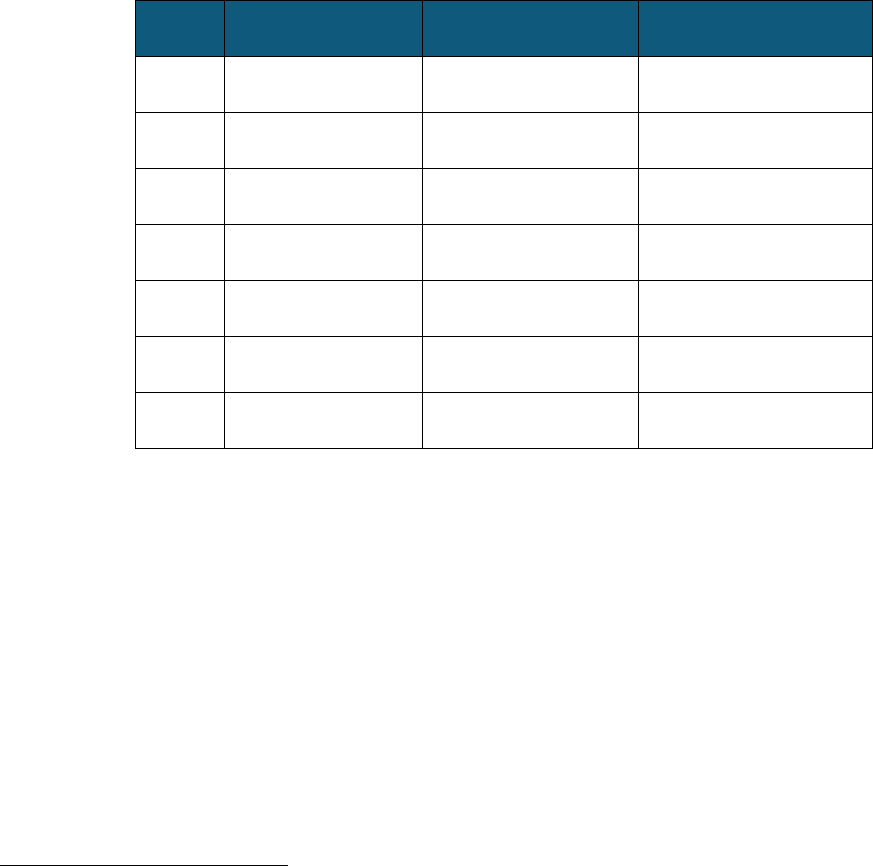

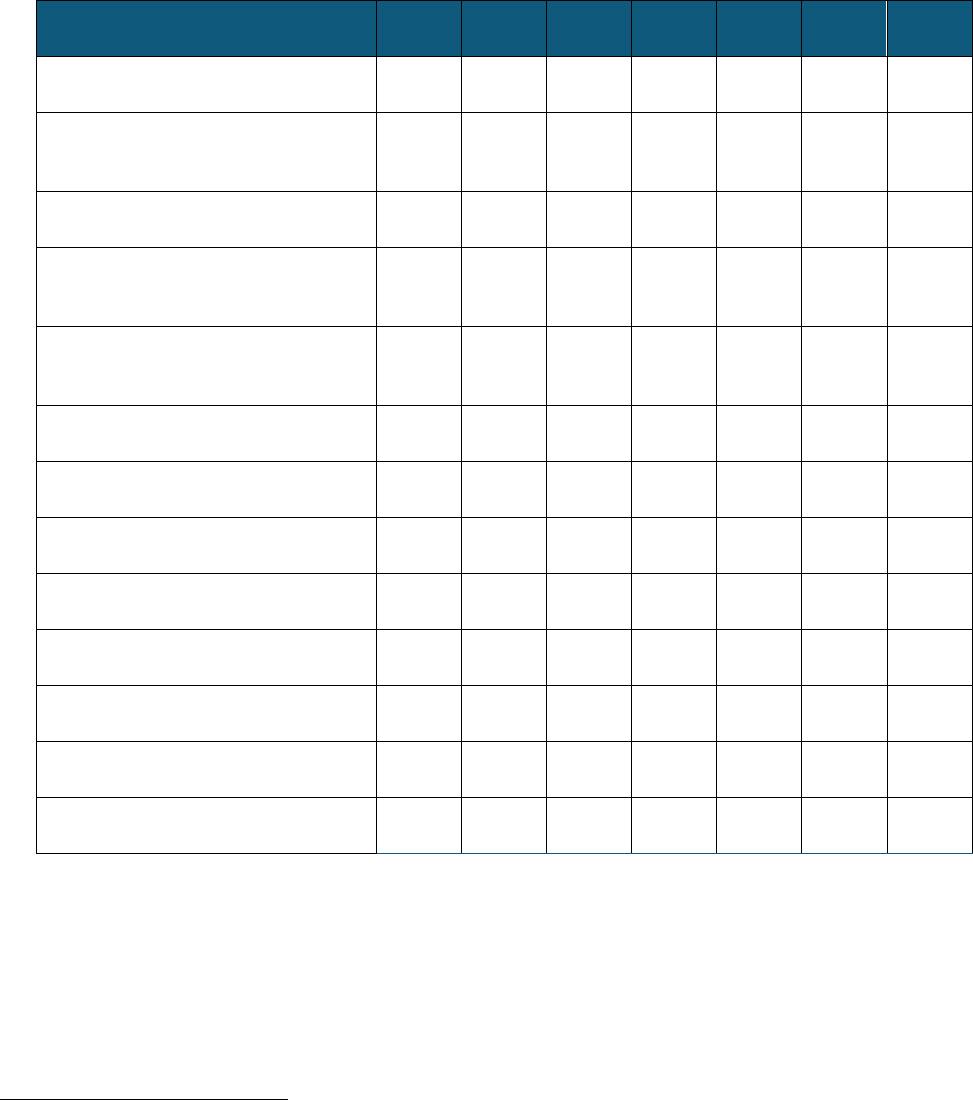

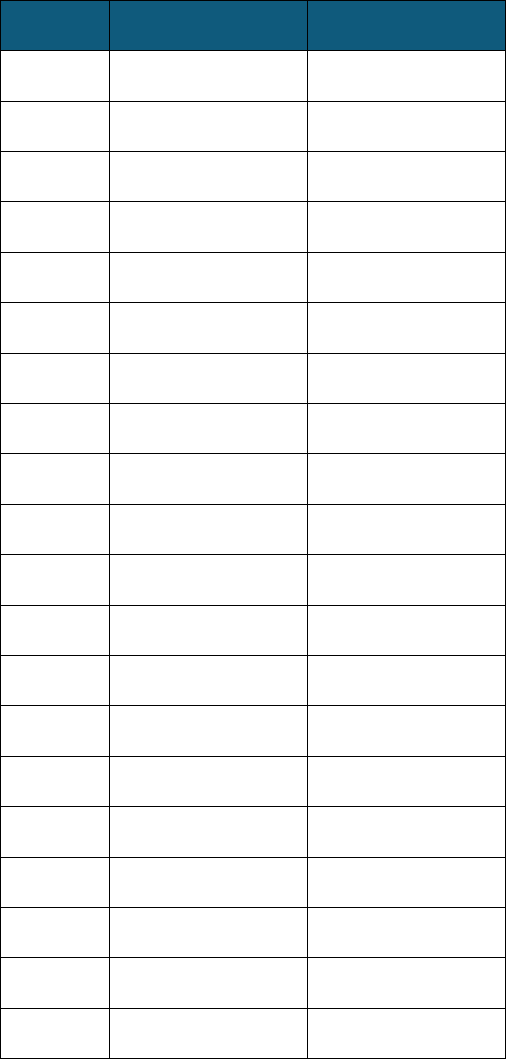

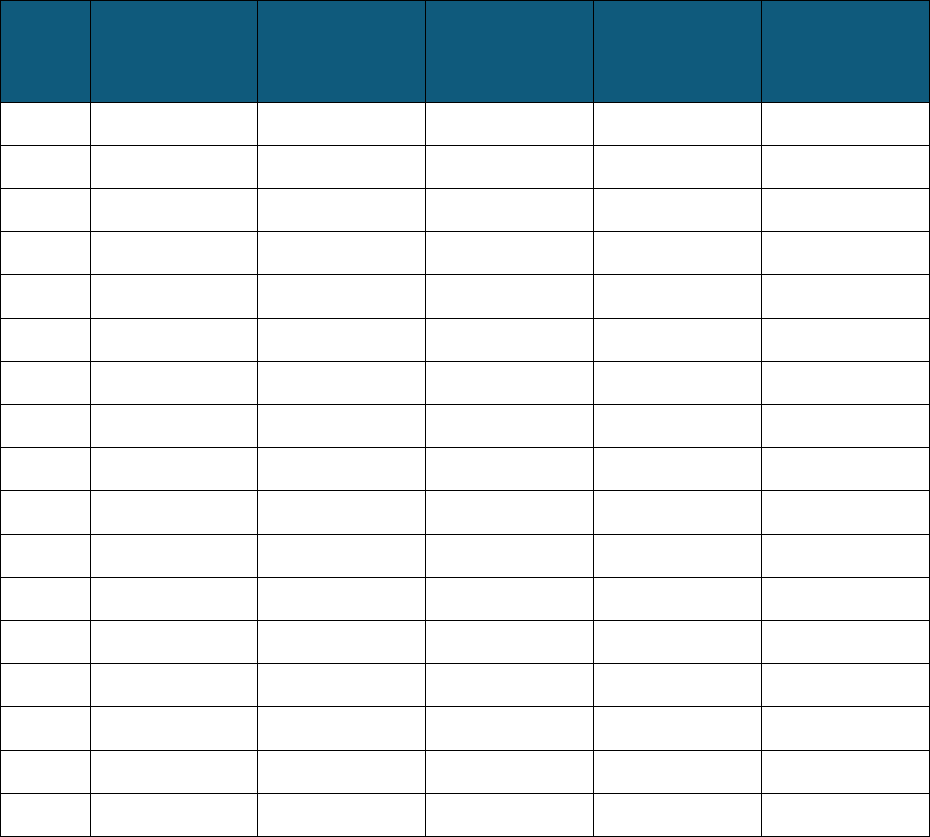

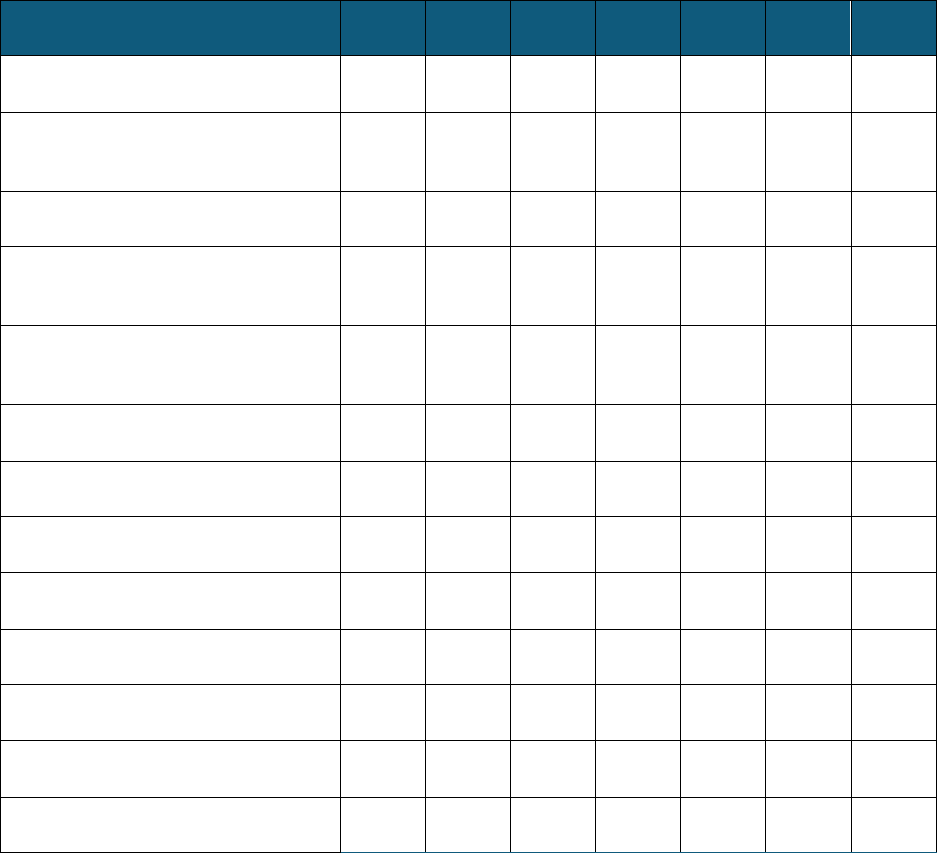

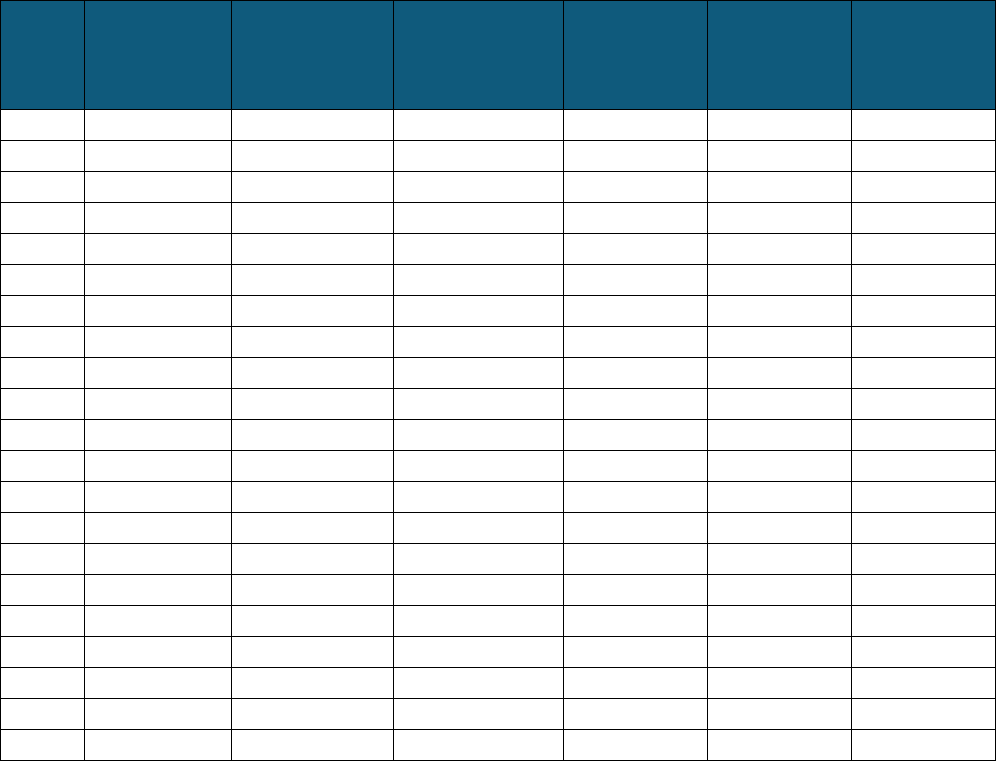

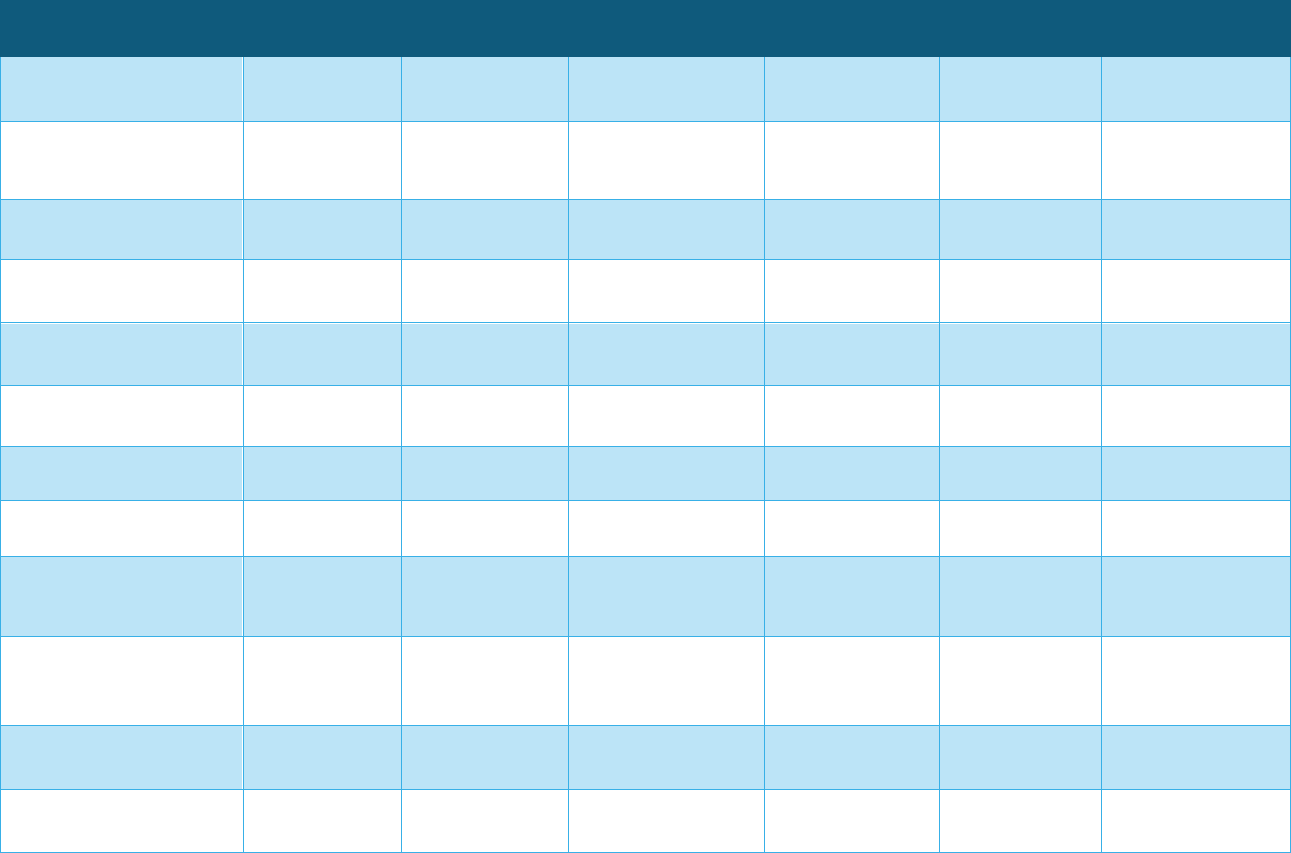

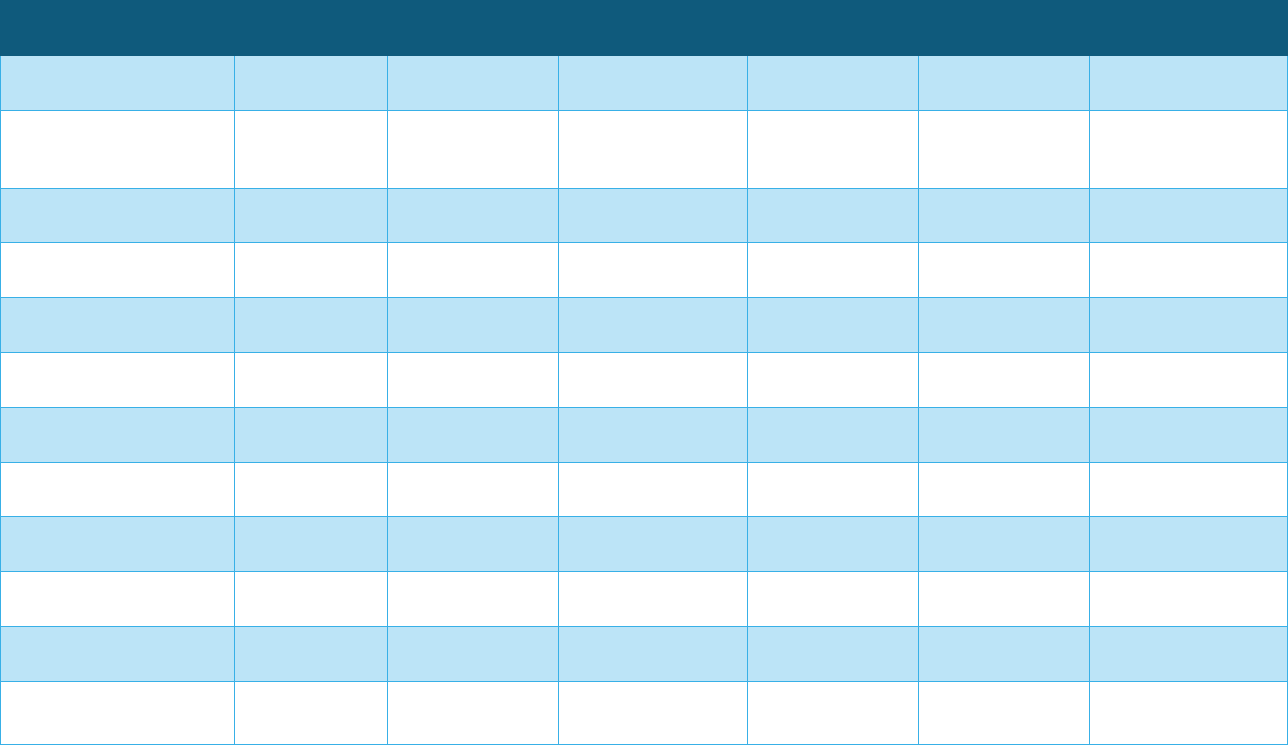

Table 1: Proposed Carbon Intensity Benchmarks for Gasoline and Fuels Used as a Substitute for Gasoline

24

Year

Average Carbon

Intensity

(gCO

2

e/MJ)

2010 Reporting Only

2011 95.61

2012 95.37

2013 97.96

2014 97.96

2015 97.96

2016 96.50

2017 95.02

2018 93.55

2019 93.23

2020 91.98

2021 90.74

2022 89.50

2023 88.25

2024

a

87.01

2025

b

80.73

2026 78.50

2027 76.26

2028

74.03

δ

2029

71.79

δ

2030

69.55

δ

24

Benchmarks for years 2011, 2013, 2016, 2019, and 2024 reflect reductions from revised base year (2010) CI

values for California Reformulated Gasoline that were calculated using the CI for crude oil supplied to California

refineries. For more information, see Table 1 in Appendix A.

19

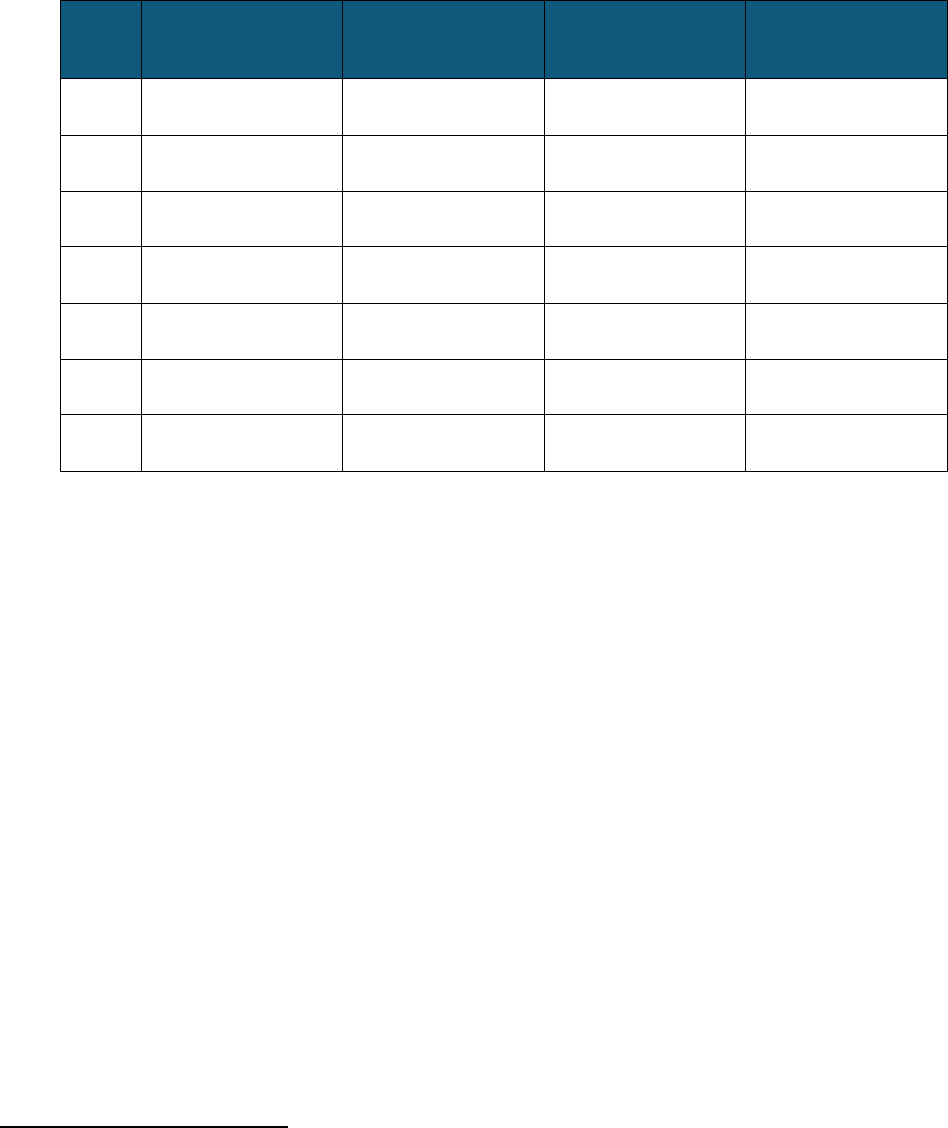

Year

Average Carbon

Intensity

(gCO

2

e/MJ)

2031

65.08

δ

2032

60.61

δ

2033

56.14

δ

2034

51.67

δ

2035

47.20

δ

2036

42.73

δ

2037

38.26

δ

2038

33.78

δ

2039

29.31

δ

2040

24.84

δ

2041

21.86

δ

2042

18.88

δ

2043

15.90

δ

2044

12.92

δ

2045

9.94

δ

a

The benchmark for years 2024 through 2045 reflect reductions from revised base year (2010) CI Values for

CaRFG (99.15).

b

The benchmark schedule in 2025 has been updated to include a 5% increase in stringency, achieving an

18.75% CI reduction compared to the 13.75% CI reduction specified in the 2018 adopted regulation.

δ These CI targets may be accelerated by the Automatic Acceleration Mechanism based on the regulatory criteria

specified in section 95484(b) in the proposed Regulation Order (Appendix A).

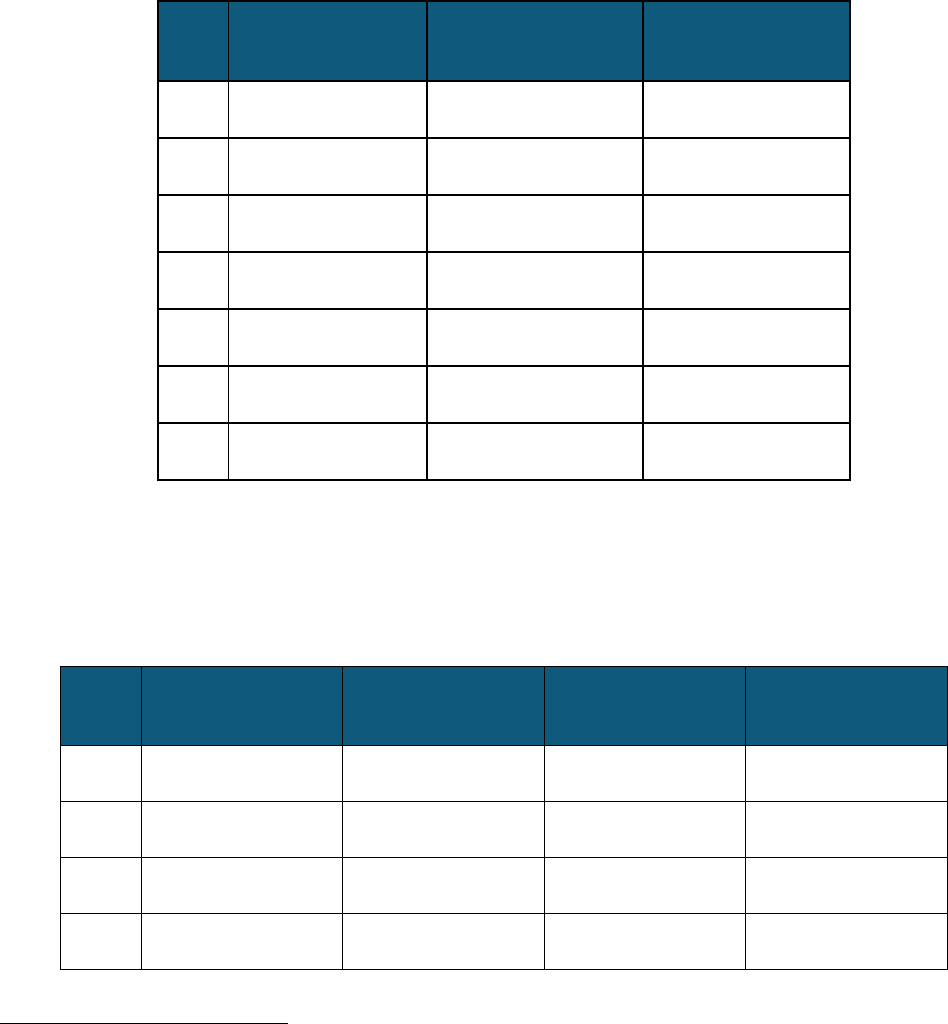

The process for determining the annual carbon intensity benchmarks is detailed in Chapter VIII

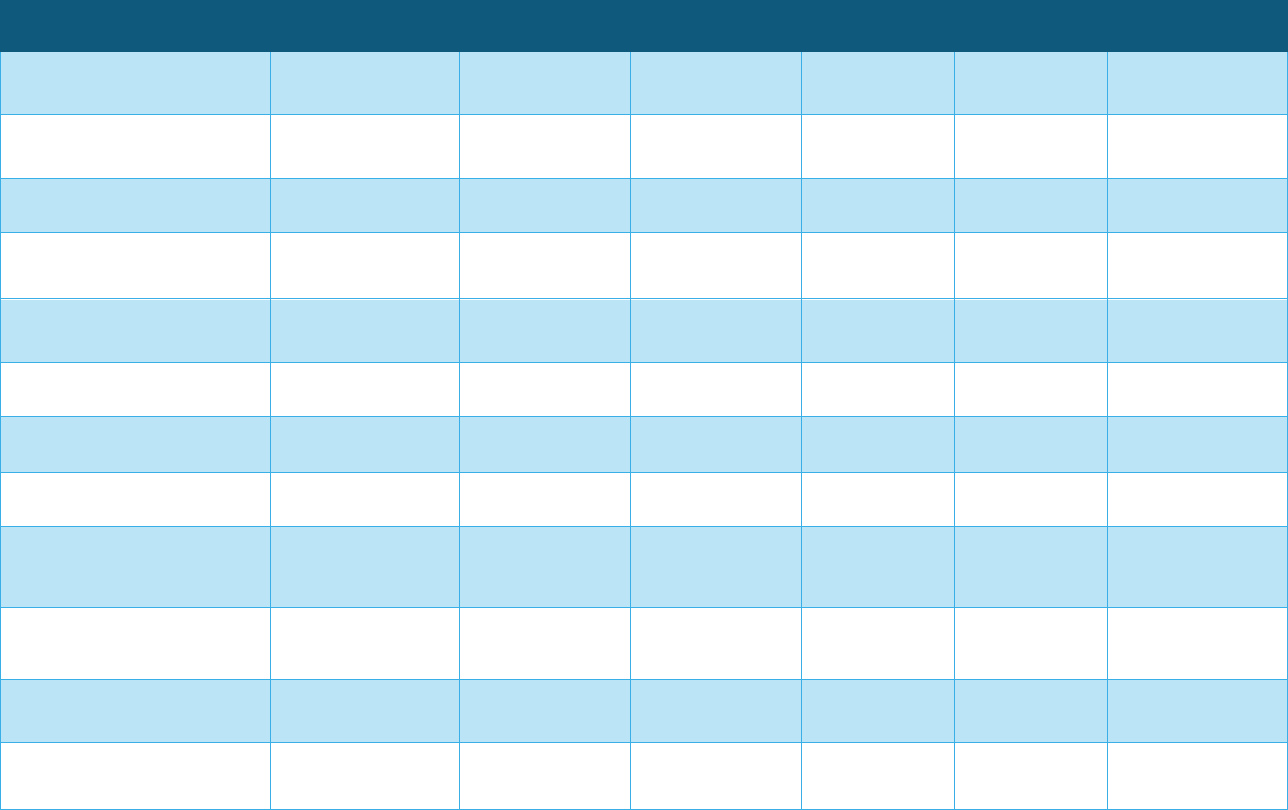

and Appendix C-1. Other proposed changes are identified in Table 2 below and include

eliminating the current LCFS exemption for intrastate fossil jet fuel starting in 2028, expanding

ZEV infrastructure crediting to the medium- and heavy-duty (MHD) sector, and adding

hydrogen-based and electricity-based transaction types to be included in the third-party

verification program for data reported under LCFS.

Additionally, amendments are proposed to further streamline existing requirements of the

LCFS regulation and to update program tools and data.

Table 2 provides a summary of the proposed changes to the regulation. Staff began

conceptually discussing many of these items through public workshops initiated in October of

2020, hosting nine workshops and two community meetings through August 2023. The

pre-rulemaking public process is detailed in Chapter XI.

20

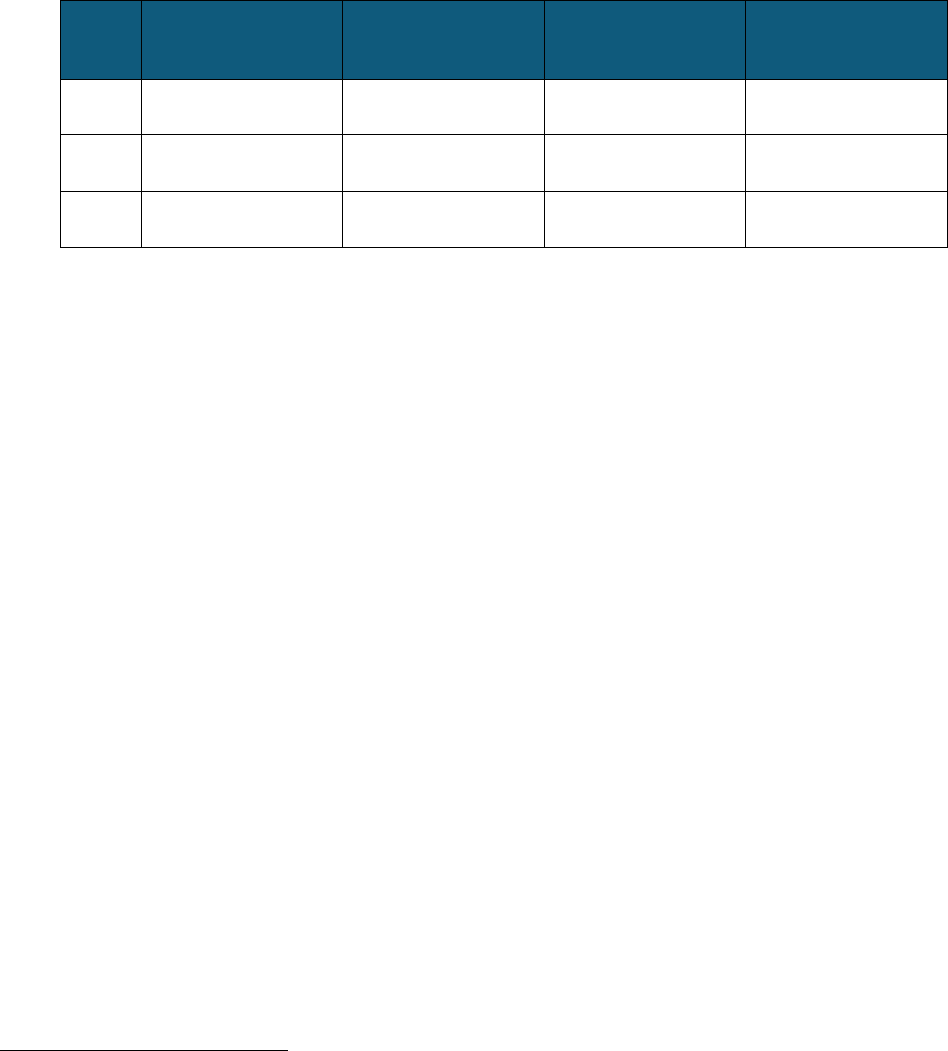

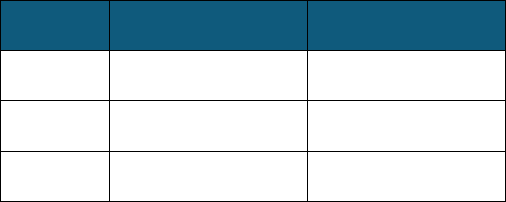

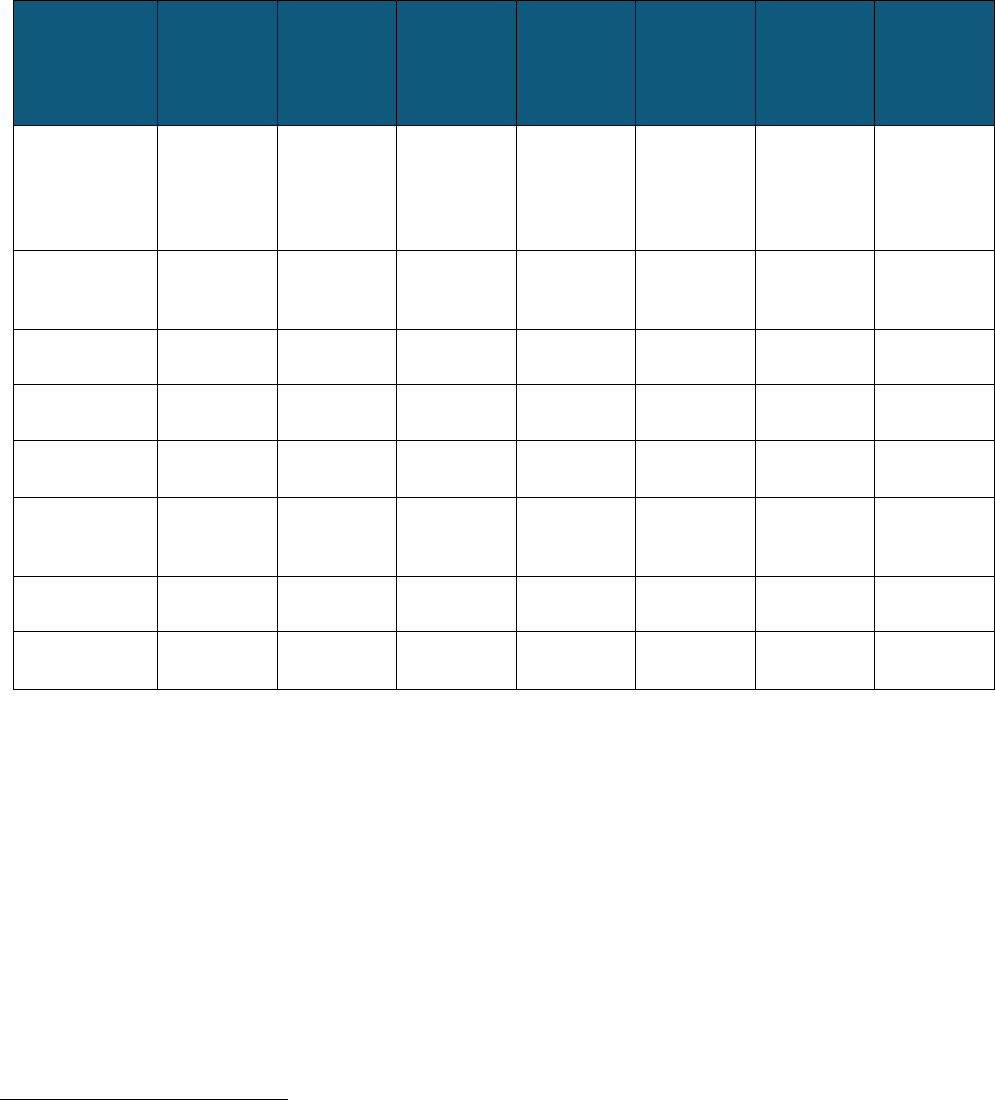

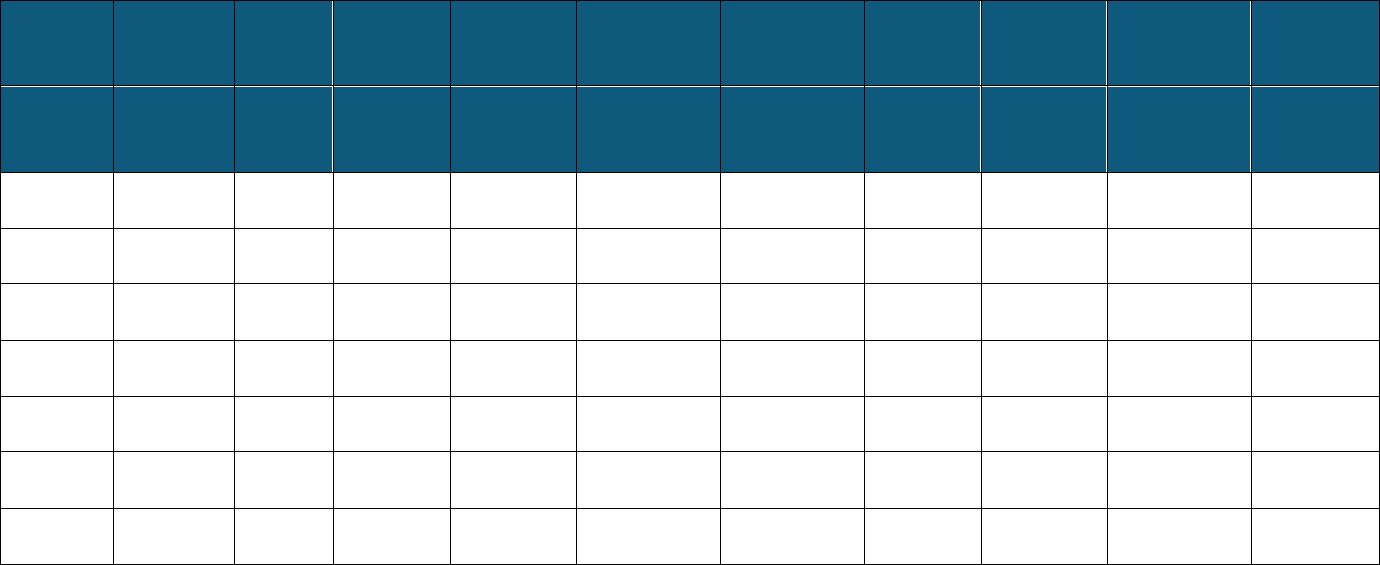

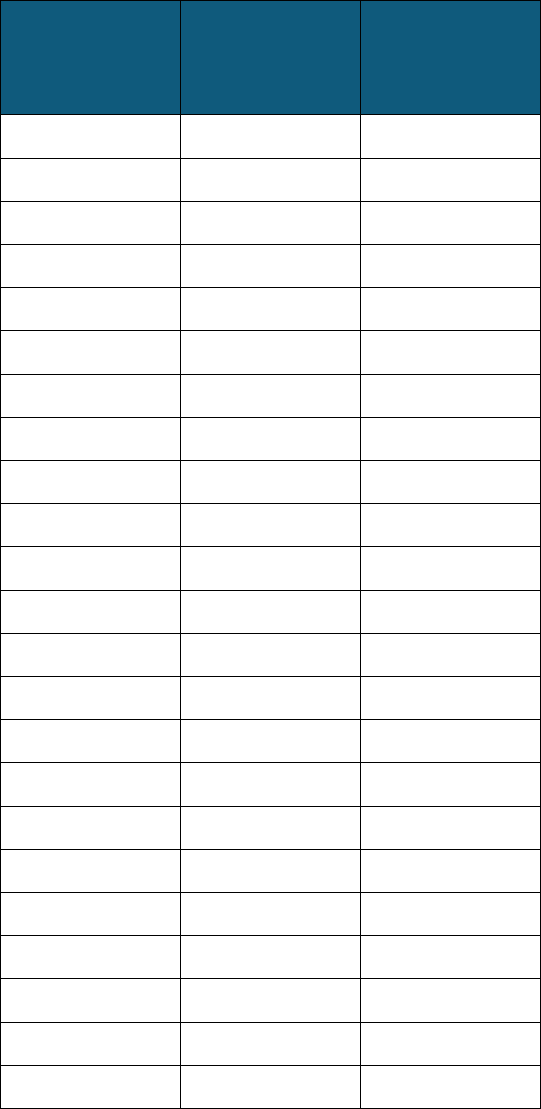

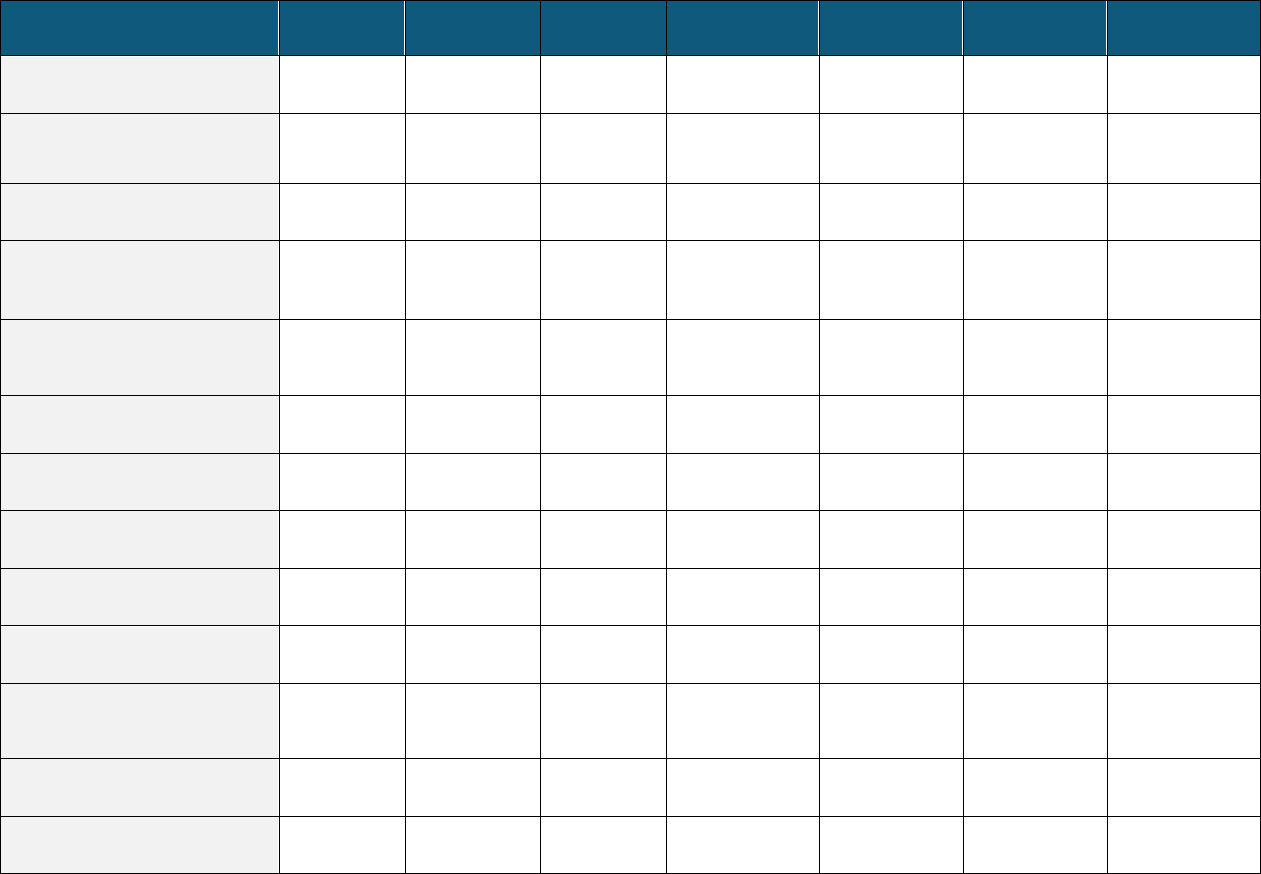

Table 2: Summary of Proposed Regulatory Amendments to the LCFS Regulation

Topic Proposed Regulatory Updates

General

Minor updates for typographical errors and specifications that do not

materially affect requirements

Update terminology for Data Management System

Compliance, Program

Benchmarks, and Credit

Generation

Strengthen the carbon intensity benchmarks both pre- and post-2030

Include a step-down of the CI benchmark in 2025 and a mechanism to

automatically strengthen the carbon intensity benchmarks based on defined

market conditions

Eliminate exemption for intrastate fossil jet fuel, beginning in 2028

Modify crediting potential for zero-emission forklifts with lift capacities less

than 12,000 lbs

Allow all fuels to be added to buffer account, instead of only liquid fuels

Equity-Focused Improvements

Focus and increase investment requirements of residential base credit

proceeds in ways that provide benefits for disadvantaged, low-income, rural,

and tribal communities

Extend and focus ZEV infrastructure crediting for light-duty vehicles in

disadvantaged, low-income communities, or rural communities

Expand ZEV infrastructure crediting to the medium- and heavy-duty sector to

support ZEV infrastructure needed for medium- and heavy-duty ZEVs

operating in heavily-impacted freight corridors

Entities and Eligibility Include Multi-Family residences as Non-Residential

Modify definition of fuel supply equipment (FSE) for electric transport

refrigeration units

Fuel Pathway Applications and

CI Determination

Update LCA modeling tools and emission factors

Include a Tier 1 Calculator for hydrogen

For projects breaking ground after December 31, 2029, add deliverability

requirement for pipeline-injected biomethane and phase out pathways for

avoided methane crediting by 2040 for biomethane used for transportation

and 2045 for biomethane used for hydrogen production

Add provisions for indirect accounting of low-CI hydrogen injected into

hydrogen pipelines

Add sustainability requirements for crop- and forestry- based feedstocks

21

Topic Proposed Regulatory Updates

Petroleum and Project-Based

Credits

Update crude oil Lookup Table

Update the Oil Production Greenhouse Gas Emission Estimator (OPGEE)

Model and process for future updates

Phase out petroleum project credit generation by 2040

Specify that direct air capture projects must be located in the United States to

generate LCFS credits

Verification Program

Add third-party verification for hydrogen and electricity data types and deferral

threshold considerations

Require third-party validation of all applications for project-based crediting.

Update deferral eligibility requirements to clarify that joint applicants are not

eligible to defer verification

Include meter calibration requirements for project and pathway applications

22

II. The Problem that the Proposal is Intended to Address

In order to implement the 2022 Scoping Plan Update, California needs to reduce emissions by

driving down fossil fuel demand in transportation, transitioning to zero-emission technology

wherever feasible, and increasing the supply of low-carbon alternative fuels as quickly as

possible. In this chapter, staff provides a description of the purpose of this rulemaking and how

the proposed amendments to the LCFS support the State’s climate and air quality targets. A

description, purpose, and rationale for each of the proposed updates and revisions are

provided in Appendix E.

To implement these objectives, staff is proposing a suite of amendments to the regulation to:

• Improve California’s long-term ability to support the production and use of increasingly

lower-CI transportation fuels and to improve the program’s overall effectiveness;

• Update the annual carbon intensity benchmarks through 2030 and establish more

stringent post-2030 benchmarks in alignment with the 2022 Scoping Plan Update;

• Increase the flexibility of the program to adjust for potential future market

overperformance by including a mechanism that would automatically accelerate the

compliance targets under certain conditions;

• Include a step-down in the near-term CI target to further support ambition;

• Incentivize fuel production and refueling infrastructure buildout needed to meet

California’s long-term climate goals and reduce dependence on petroleum fuels,

including opportunities to leverage federal funding for low-carbon hydrogen production

and ZEV fueling, and support the transition of biomethane fuel pathways for combustion

out of transportation;

• Update standard values in the regulation, including emission factors, as well as life

cycle assessment (LCA) modeling tools to use more detailed or recent data;

• Streamline implementation of the program; and

• Make minor updates for typographical errors and clarifying specifications.

A. Strengthen the Annual Carbon Intensity Benchmarks Pre- and Post-2030

Staff last revisited the annual carbon intensity benchmarks in 2018, following the approval of

the 2017 Scoping Plan Update, which focused on achieving the 2030 SB 32 GHG reduction

target. Through the 2018 rulemaking, the Board extended the carbon intensity benchmarks

from a 10% reduction in 2020 to a 20% reduction in 2030 to align with SB 32 and the 2017

Scoping Plan Update. The climate policy landscape has continued to evolve since the 2018

rulemaking. In 2022, the Governor signed AB 1279, which requires an 85% reduction in

anthropogenic GHG emissions below 1990 levels by 2045. The 2022 Scoping Plan Update

lays out a path to achieve these targets and achieve carbon neutrality by 2045. Staff is

proposing to update the LCFS program in response to current legislative direction and the

2022 Scoping Plan Update. Along with this high-level policy direction and technology-forcing

emission standards and other policies adopted by the Board, low-carbon technology uptake is

accelerating. Renewable diesel capacity has grown substantially and far exceeds what was

previously modeled in 2018 when the current CI benchmarks were established. Electricity and

hydrogen used as vehicle fuels have increased over 50% between 2019 and 2022 and are far

outpacing the projections staff used to establish the existing CI benchmarks during the

23

previous 2018 rulemaking. This trend is expected to continue, as California implements the

ACC II, ACT, ACF, Innovative Clean Transit, Cargo Handling Equipment, Ocean Going

Vessels at Berth, Clean Miles Standard, Transport Refrigeration Unit, and In-use Locomotive

regulations.

There is also much progress in the liquid and gaseous alternative fuel spaces. Biofuel

production capacity has increased substantially in recent years, with many announcements

nationwide and in California for new or expanded capacity. Momentum for alternative fuels is

growing at the national level, as well. Biomethane supplies have also increased as more

methane capture projects are developed.

Taken together, these trends suggest that the market is outpacing previous fuels and crediting

projections used for the 2018 LCFS benchmark modeling and that re-evaluation of near-term

targets is needed to accelerate action and plan beyond 2030. Staff recommends strengthening

the pre- and post-2030 carbon intensity benchmarks to accelerate GHG reductions in

transportation fuel. As part of this overall strengthening of the benchmarks, staff also

recommends a near-term step-down of the 2025 benchmark and an acceleration mechanism

to adjust the CI benchmarks if market conditions warrant.

Achieving California’s mid- and long-term GHG and air quality goals will require a portfolio of

low-carbon transportation fuels in amounts well beyond the current amounts. The

transportation sector remains the largest contributing source of GHG emissions in the State

inventory. The LCFS has been an effective measure for increasing the use of low-carbon

alternatives to fossil fuels in California by providing significant economic benefits to the

credit-generating entities who participate in the program, including municipal transit agencies,

alternative fueling facilities, equipment service providers, fuel producers, and project

developers across the United States and abroad. For example, the 2020 California GHG

Emissions Inventory

25

shows that California continues to stay below its 2020 target for

emissions. The data shows a decline in emissions from transportation, supported by the LCFS,

which is driving increasing use of alternative fuels in the transportation sector.

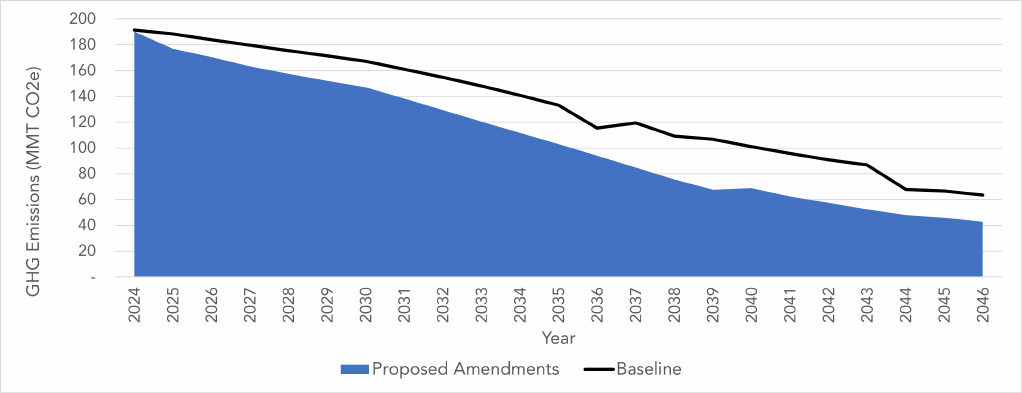

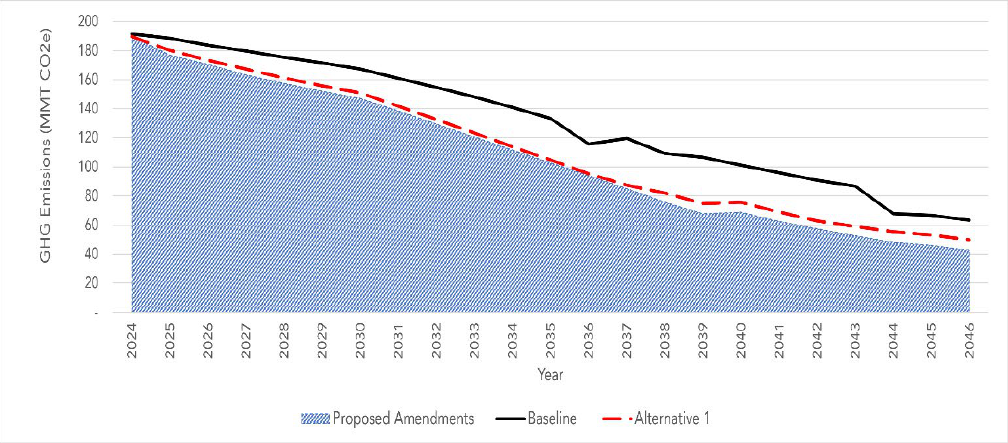

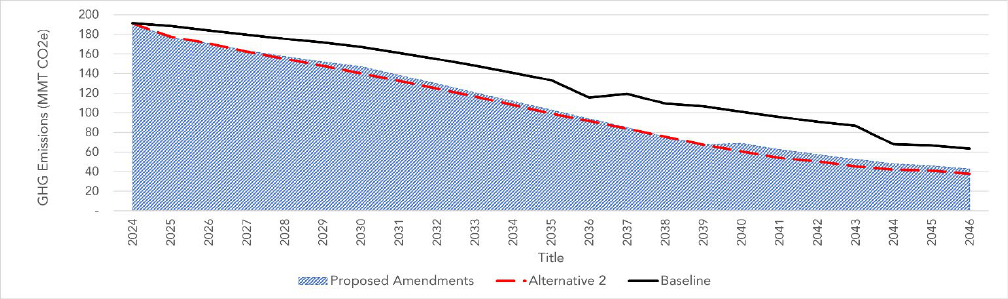

The proposed amendments are expected to reduce life cycle GHG emissions of transportation

fuels consumed in California by about 558 million metric tons in carbon dioxide equivalent

(MMTCO

2

e) cumulatively from 2024 to 2046 as compared to business as usual (see Chapter

IV of this Staff Report for additional discussion of the projected GHG benefits). Greater

diversification of the State’s fuel portfolio will also support California’s ongoing efforts to

improve ambient air quality by displacing demand for fossil fuels. Chapter V of this Staff Report

summarizes the air quality and public health benefits of the proposed regulation.

The LCFS regulation defines a carbon intensity benchmark for each year. The current LCFS

benchmark schedule was designed to help California achieve the statutory target of 40% GHG

emissions reduction by 2030, in line with the 2017 Scoping Plan Update and SB 32. However,

the 2022 Scoping Plan Update calls for an accelerated deployment of fuels and ZEVs in

support of achieving a 48% reduction of GHGs by 2030 and 85% below 1990 levels by 2045.

25

California Air Resource Board, Latest GHG Inventory shows California remains below 2020 emissions target.

October 19, 2020. https://ww2.arb.ca.gov/news/latest-ghg-inventory-shows-california-remains-below-2020-

emissions-target

24

Using market data and techno-economic models to evaluate a variety of transportation fuel

pathways, staff conducted a scenario analysis that informed the pre- and post-2030 target and

annual benchmarks for carbon intensity reduction through 2045. This analysis helps staff

explore possible compliance outcomes and facilitates an improved understanding of LCFS

economics and compliance feasibility for different policy choices in each scenario.

Staff developed the California Transportation Supply (CATS) model to evaluate the California

fuel market and estimate an optimal fuel supply that may be delivered to California under

various scenarios. Since CATS, and really no modeling tool, can fully capture all real-world

conditions, the tool is primarily being used to compare results of different policy changes

across the different scenarios. The CATS model is an optimization model that seeks to

minimize the cost of supplying all defined fuel pools such that fuel demand constraints are met.

The CATS model selects the fuel mixes likely available for California that minimize the cost of

supplying all transport fuel demand in the State while meeting technology and policy

constraints. The outputs from the CATS model do not constitute a forecast of credit prices, but

rather how the market may evolve in response to different policy changes that may, or may

not, be implemented.

The optimization model is constrained by a set of policies, technologies, and cost

considerations that are intended to approximate current and future market conditions under

different scenarios. Anticipated mobility demand each year is used to estimate energy demand

by vehicle technology type (e.g., light-duty electric vehicle, gasoline vehicle, etc.), and the

model then identifies a variety of fuel production pathways that could be optimally used to meet

that demand given costs and policy considerations. Staff developed feedstock supply curves

and feedstock to fuel conversion pathways for the model that are detailed in the California

Transportation Supply (CATS) Model v0.2 – Technical Documentation.

26

Based on feedback received from stakeholders, staff evaluated a wide range of CI benchmark

trajectories. Scenarios modeled both in-house by CARB and by external stakeholders indicate

that a reduction of at least 30% by 2030 and 90% by 2045 is achievable and necessary to

accelerate decarbonization of the transportation fuels sector and support the State’s broader

climate goals. Figure 6 shows staff’s proposed benchmarks as compared to the benchmarks in

the current regulation for the years 2024 through 2045. When considering the full period from

2024 through 2046, staff’s proposal achieves 558 MMT more cumulative reductions relative to

the current regulation. Chapter VIII and Appendix C-1 of this Staff Report provide additional

details on the data sources and methodology that staff has relied on to evaluate feasible LCFS

compliance scenarios.

26

California Air Resources Board, California Transportation Supply (CATS) Model v0.2 – Technical

Documentation for August 2023 Example Scenario. August 2023. https://ww2.arb.ca.gov/sites/default/files/2023-

08/CATS%20Technical_1.pdf

25

Figure 6: Current and Proposed Annual Carbon Intensity Benchmarks

Additionally, the transportation fuels market is evolving quickly due to technological and

economic breakthroughs, regulatory requirements, new federal incentives, and other

jurisdictions implementing similar programs. This has resulted in rapid shifts in the market,

particularly from rapidly growing ZEV market and conversion of fossil refineries to biofuel

production, which have resulted in rapid and significant credit generation. To accommodate

documented rapid advances in transportation fuel decarbonization that have already occurred,

and which could occur again due to these rapid changes, the proposed amendments include

both a near-term step-down in CI benchmark stringency in 2025, and an Automatic

Acceleration Mechanism (AAM).

A step-down in stringency was strongly supported by feedback provided by stakeholders,

particularly in response to February and May 2023 technical workshops. The step-down

reflects the current effectiveness of the program, which suggests that the pace of CI reductions

can be increased through the benchmarks.

Staff is proposing to include an AAM to increase the stringency of the CI benchmarks of the

program when specific regulatory conditions are satisfied. Under the current staff proposal, the

AAM would advance the upcoming year’s CI benchmark, and all subsequent years by one

year. The acceleration mechanism provides a clear signal regarding how and when the

benchmarks would be adjusted. An AAM can support the deeper transportation sector

decarbonization needed through mid-century by increasing regulatory clarity for the market,

acting alongside existing provisions that also help to provide program certainty, such as the

maximum credit price

27

and the Credit Clearance Market (CCM).

28

27

Cal. Code Regs., tit. 17, § 95487(a)(2)(D).

28

Cal. Code Regs., tit. 17, § 95485(c).

26

An AAM would operate to potentially increase program stringency, using regulatory criteria, to

accommodate documented rapid advances in transportation fuel decarbonization. An AAM

would operate in a way that is predictable and easy to understand, based on publicly available

data, and would bolster market stability during periods where credit generation rapidly and

consistently outpaces deficit generation. Similar to maximum price and CCM provisions, an

AAM would play an important role in supporting LCFS implementation, deterring market

manipulation, and providing the certainty necessary for the long-term investments required to

meet the State’s decarbonization goals.

Staff engaged extensively with stakeholders to develop an AAM, including holding a dedicated

workshop for this topic in May 2023. An AAM would only be activated by specific market

conditions defined in the LCFS regulations that result in a specified imbalance in the number of

credits versus deficits over a certain time period. Under staff’s proposal, the AAM would be

triggered when the credit bank to average quarterly deficit ratio exceeds three and credit

generation exceeds deficit generation based on the prior year’s reporting. If triggered, the AAM

would accelerate all subsequent CI benchmarks by one year.

B. Eliminate Exemption for Intrastate Fossil Jet Fuel

Staff is proposing to eliminate the exemption for intrastate fossil jet fuel from the LCFS

regulation starting in 2028. The aviation sector has historically relied on jet fuel produced from

fossil fuels, and fossil jet fuel is currently exempted from generating deficits in the LCFS

program. However, to achieve the deep emissions reductions called for in AB 1279 and the

2022 Scoping Plan Update, California must reduce GHG emissions from aviation.

In California, intrastate jet fuel constitutes about 10% of total jet fuel consumption and is

responsible for 2% of GHG emissions in the California transportation sector. As emissions

from other vehicle types decline, this percentage is expected to increase. Alternative jet fuel

(AJF) production has increased since it became an eligible LCFS opt-in fuel in 2019, and with

11.6 million gallons produced in 2022. This provision would be limited to flights that take off

and land within the State of California.

Momentum is growing for AJF, an alternative liquid fuel that can displace fossil jet fuel without

engine modifications, along with interest in zero-emission technologies for aviation. At the

federal level, a tax credit of up to $1.25 per gallon is available to sustainable aviation fuel

(SAF) producers.

29

In alignment with the federal support available for SAF, Governor Newsom

highlighted the need to transition to low-carbon alternatives in his July 2022 letter to the CARB

Chair, in which he directed CARB to adopt a 20% clean fuels target for the aviation sector.

30

The 2022 Scoping Plan Update anticipates a major shift away from fossil jet fuel by 2045,

including 20% zero-emission aviation.

29

Internal Revenue Service. Sustainable Aviation Fuel Credit webpage. (Updated on January 31, 2023).

https://www.irs.gov/credits-deductions/businesses/sustainable-aviation-fuel-credit

30

California Office of the Governor, Governor’s Letter to Chair Randolph. July 22, 2022.

https://www.gov.ca.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/07.22.2022-Governors-Letter-to-CARB.pdf?emrc=1054d6

27

Several airlines have also announced GHG emission reduction targets, as well as multi-year

agreements to source SAF for their operations. For example, United Airlines,

31

Southwest

Airlines,

32

and American Airlines

33

have released plans to achieve carbon neutrality by 2050.

Additionally, Alaska Airlines set new climate goals that include net-zero carbon emissions by

2040.

34

Finally, Delta Airlines has a goal to replace 10% of its fossil jet fuel with SAF by the

end of 2030.

35

Production is ramping up to meet the increasing demand for low-carbon

incentives. For example, multiple refineries in California are transitioning their existing facilities

to produce bio-based alternative fuels, including AJF. AJF is a viable low-carbon alternative

that can further reduce aviation carbon dioxide emissions and currently generates credits in

the LCFS program. Adding fossil jet fuel as a required fuel under the program will build on the

momentum in the aviation industry.

C. Expand Zero Emission Vehicle Infrastructure Crediting

During the 2018 rulemaking, the Board adopted the HRI and FCI provisions. These two

crediting opportunities were designed to incentivize zero-emission light-duty vehicle (LDV)

refueling infrastructure ahead of anticipated ZEV demand. The intent of these provisions was

to help remove the “chicken-and-egg” issue of vehicle demand waiting on refueling

development, and refueling infrastructure waiting on vehicle demand, by incentivizing rapid

buildout of public refueling infrastructure. Dispensed fuel receives crediting in the LCFS, and

these provisions added crediting for unused capacity at approved stations. The provisions

have supported the buildout of dozens of hydrogen stations and thousands of fast chargers in

California and play a key role in supporting the overall transition to ZEV technology, driven in

large part by the ACC II regulation. New applications for these crediting provisions sunset at

the end of 2025.

Staff is proposing amendments to expand the current ZEV infrastructure crediting provisions

by adding crediting for MHD infrastructure and extending the LD crediting. As the State

transitions to widespread ZEV deployment, it is imperative that all individuals in the State have

access to cleaner technologies. Therefore, staff is proposing to continue the HRI and FCI

incentivization for light-duty vehicle refueling in low-income, rural, or disadvantaged

communities. This focused eligibility requirement aligns with identified priorities in the Clean

Transportation Incentives Funding Plan

36

, which provides funding for ZEVs deployed in these

regions. Staff is also proposing to allow new light-duty FCI (LD-FCI) applications be located